That’s it, I’m here. What could there be at the end of this route?

Transitional spaces, in other words, liminal spaces or thresholds, are physical or metaphorical representations of the stage ‘in between’ two other distinct stages. Hallways, waiting rooms, passageways, empty parking lots, or areas of transport like airports or train stations, all fall into this category. When entering a threshold, the person is neither here, or there, in a place that is rather unrecognizable, but yet intimately known. Balancing between the existent and the non-existent, the real and the surreal, the physical and the mental, liminal spaces are challenging both the notions of space and time within the context of a narrative.

The relation to time

‘The heterotopia begins to function at full capacity when men arrive at a sort of abso- lute break with their traditional time.’ (Foucault, 1984)

A liminal space prepares and introduces a story – and can powerfully emerge within the ‘cracks’ of traditional notions. This state of being can be rather unsettling and disorienting, but is pivotal in order to complete one’s transition.

Benjamin Whorf distinguishes two types of spatial and temporal realities, one inextricable to the other; the manifested (objective) and manifesting (subjective).

‘It (manifested reality) includes all that is or has been accessible to the senses, the present as well as the past, but it excludes everything that we call the future. Manifesting or subjective reality is the future and the mental. It lies in the realm of expectancy and of desire.’ (Yi-Fu Tuan, 1977) Within this framework, liminal spaces can exist between the manifested and the manifesting realities, amplifying the tension between the objective and the subjective realms. Time becomes fluid, and the visitor navigates between the tangible reality and the mental landscape of possibility. That’s where the narrative is about to unfold: when one is about to confront change, explore new identities, and ultimately reshape their journey.

The relation to space

Why is the notion of liminal so unsettlingly familiar? Maybe because it resonates with a feeling that most people recognize: being out of place.

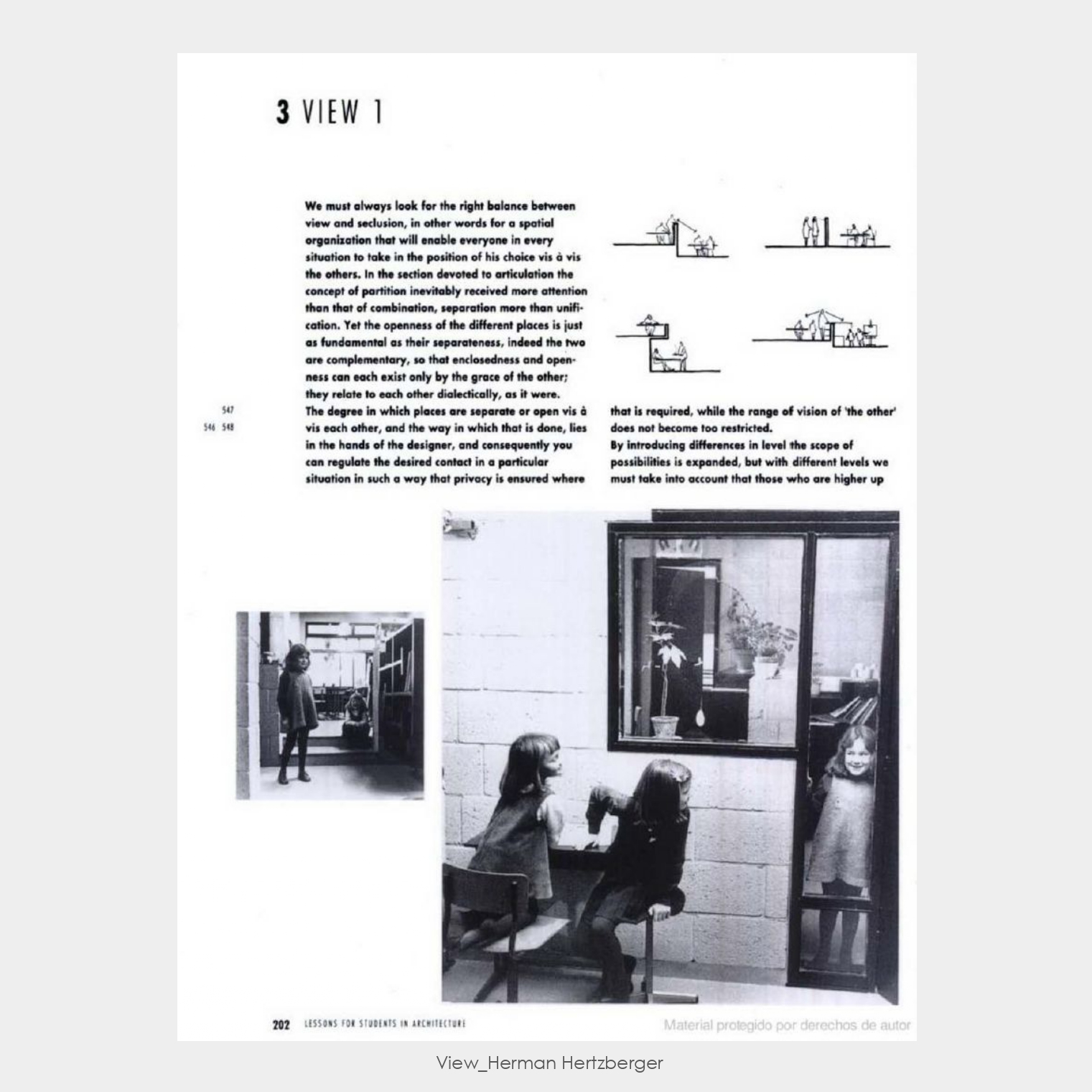

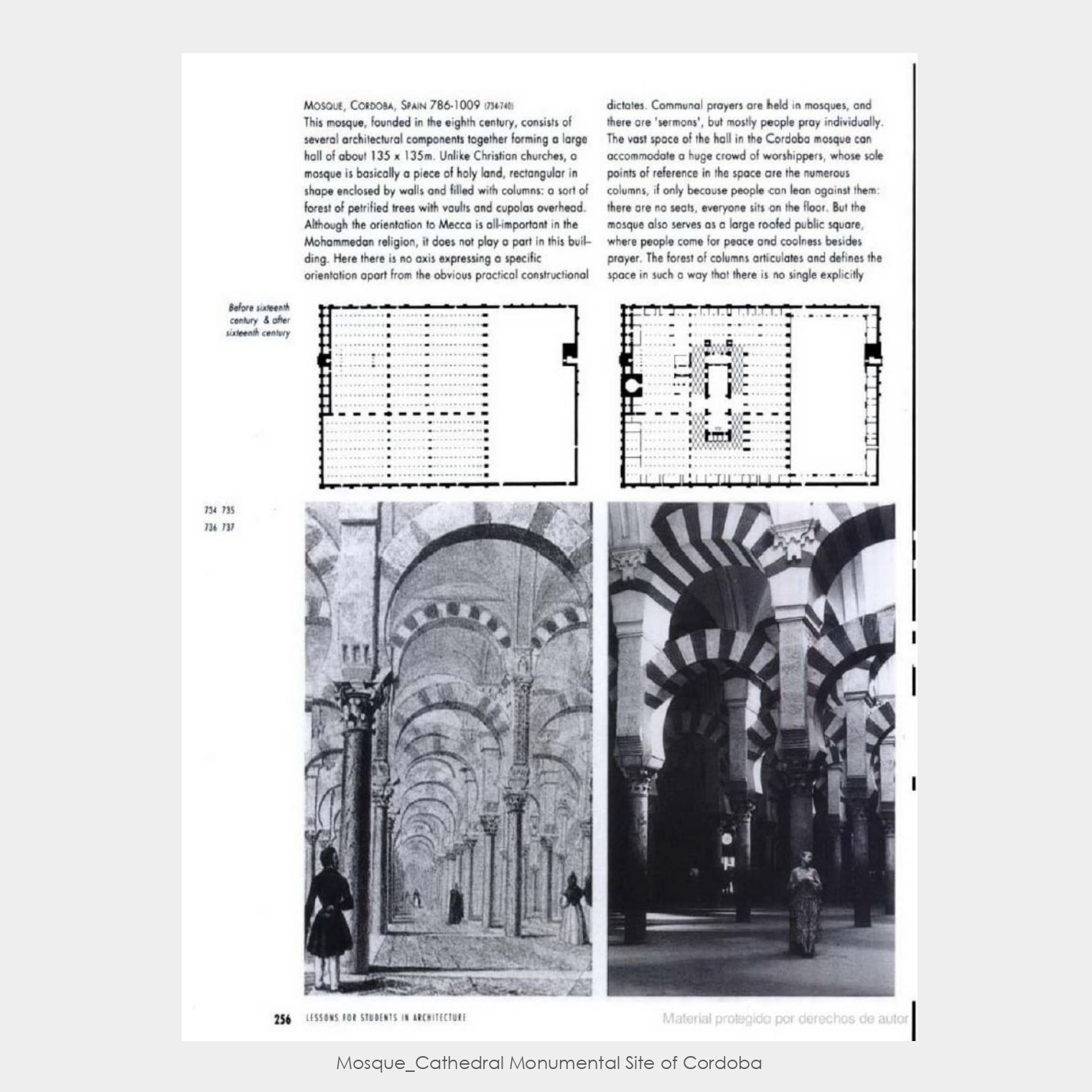

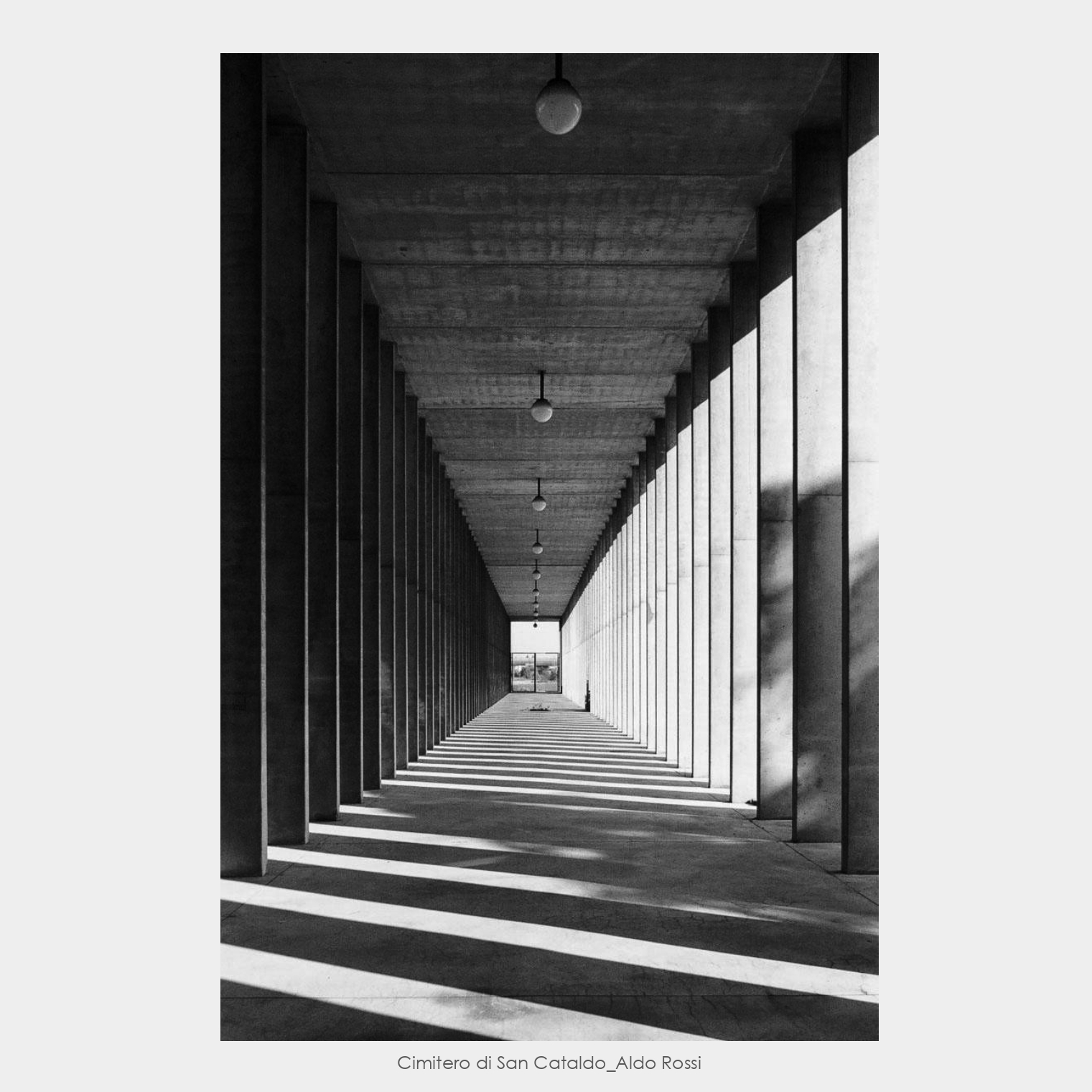

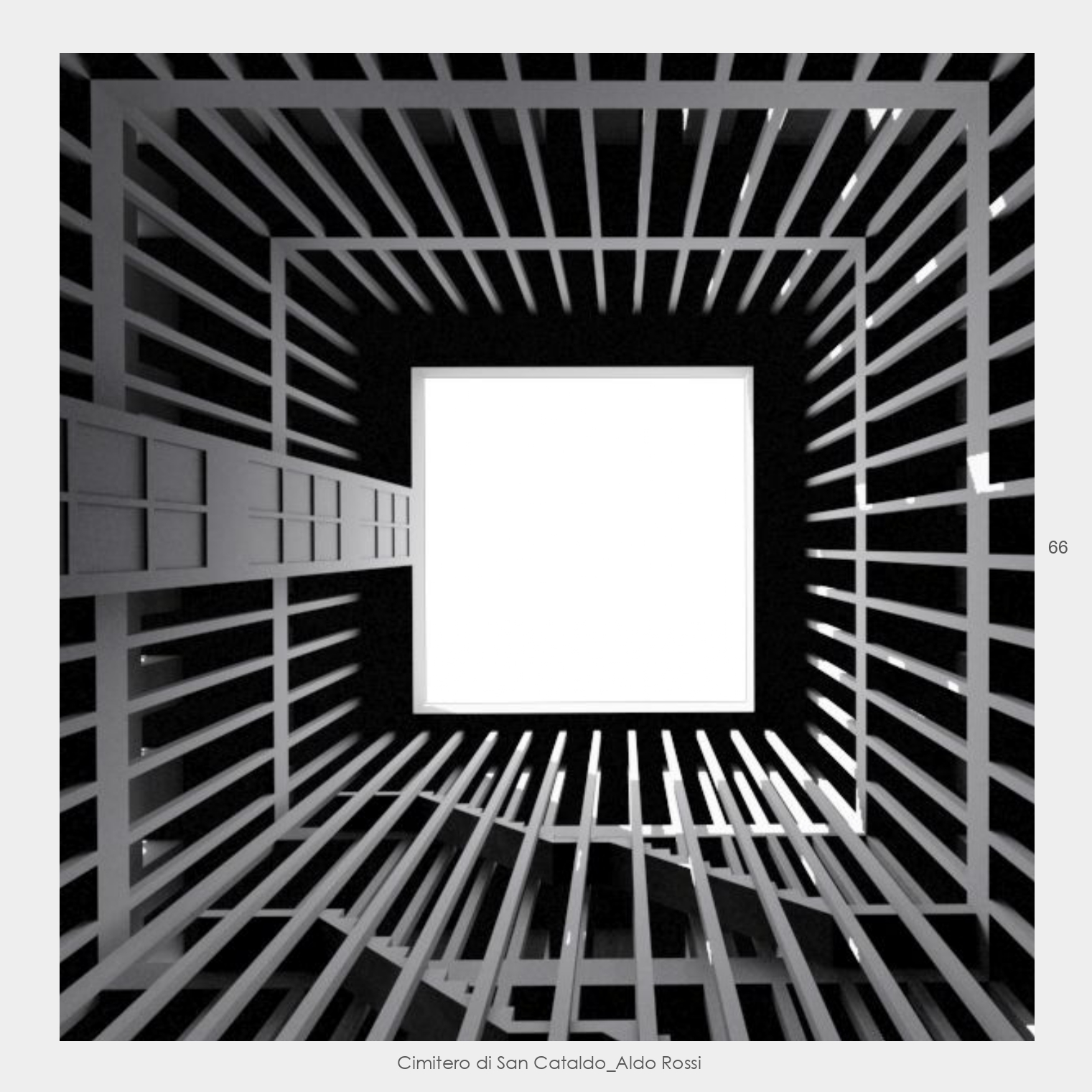

In architecture, sometimes these types of spaces are merely zones of transition within a built environment. They connect one distinct space to the other, and facilitate movement. Often overlooked, considered to be serving exclusively functionality, they come across as distant, neglected, cold and indifferent. But instead of still moments in time, these areas could use their simplicity in order to become a breeding ground for change. Instead of existing outside life rhythms, they could facilitate discourse acknowledging their unique role as places of transition. Creating an interplay between lights, shadows, materials, entering ways and exit doors, the experience within the liminal can be heightened. If the transitional space becomes the main setting, it can create a unique narrative atmosphere, emphasizing themes of uncertainty and transformation. This focus allows for deeper exploration of characters’ inner conflicts and their relationships with the environment, blurring the lines between reality and perception.

Liminal spaces hold a certain power onto them. Whether they’re physical or emotional, they are territories of uncertainty and reflection. Through their discomfort, they push the boundaries between space and time, and can be a valuable tool in order to amplify the embodied experience. In these liminal moments one can come to understand the deeper connections between place, time and itself, and face all the inevitable transitions that all these notions come with. Liminality forces introspection, compelling us to confront the unknown before emerging on the other side with a new sense of self or purpose.

And just like that, the hallway behind me dissolves. As if it was never there – or has it always been there?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bachelard, G., 1969. The Poetics Of Space. Boston: Beacon Press.

Benjamin, W., 1972. A Short History of Photography. Screen, 13(1), pp.5-26.

Berger, J., 1977. Ways Of Seeing. London: British Broadcasting Corporation.

Foucault, M. “Of Other Spaces, Heterotopias.” Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité 5 (1984).

Tuan, Y., 2018. Space and place: The perspective of experience. Minneapolis, Minn: University of Minnesota Press.

Margarita Voyatzi

is an Athens-based architect and spatial designer. She is a distinguished graduate of the

University of Thessaly, where she obtained her Master’s degree in Architecture. She also studied

architecture in Paris, at ENSA

Paris-Est. She holds

an MA in Narrative Environments from Central Saint Martins, London. She has

previously worked in practices in Amsterdam and Athens for the past four years, specializing in creating unique commercial and

retail spaces. She currently works at

Urban Soul Project, bringing her expertise to innovative design projects, translating stories into immersive,

multisensory design experiences.

How do such spaces, often devoid of explicit programmatic function, contribute to the experience and understanding of the built environment?

Can we conceive of an architecture composed solely of transitions, a fluid continuum of in-between spaces?

How do these spaces contribute to the social value of architecture?

Do they hold the key to understanding the deepest desires and anxieties of a society?

Can we decipher the social coherence of a civilization by

examining the thresholds and passages it creates in its architecture?

Can the design of thresholds shape not only our movement through space, but also the evolution of our social structures?

What is a transitional space?

How do these often-functionless spaces shape our very experience of architecture?

Do they dare to redefine boundaries?

Can we create an architecture of pure transition,

a liminal symphony of in-between?

Do these spaces defy typology, resisting categorization?

How do they imbue architecture with social value,

fostering interaction and exchange?

Do these spaces transcend the ephemeral whims of style, echoing through time and revealing the enduring essence of human habitation?

How do these often-functionless spaces shape our very experience of architecture?

Do they dare to redefine boundaries?

Can we create an architecture of pure transition,

a liminal symphony of in-between?

Do these spaces defy typology, resisting categorization?

How do they imbue architecture with social value,

fostering interaction and exchange?

Do these spaces transcend the ephemeral whims of style, echoing through time and revealing the enduring essence of human habitation?

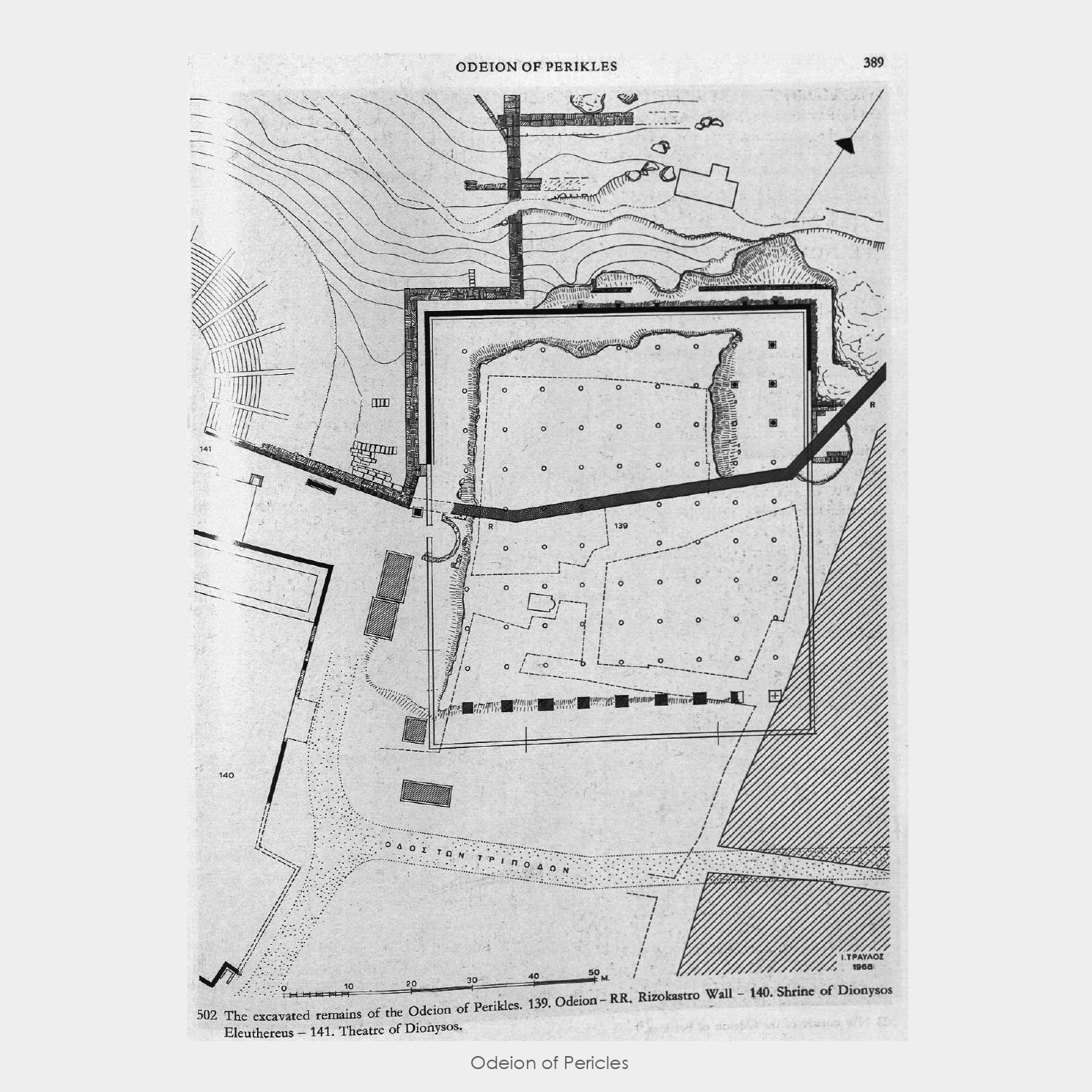

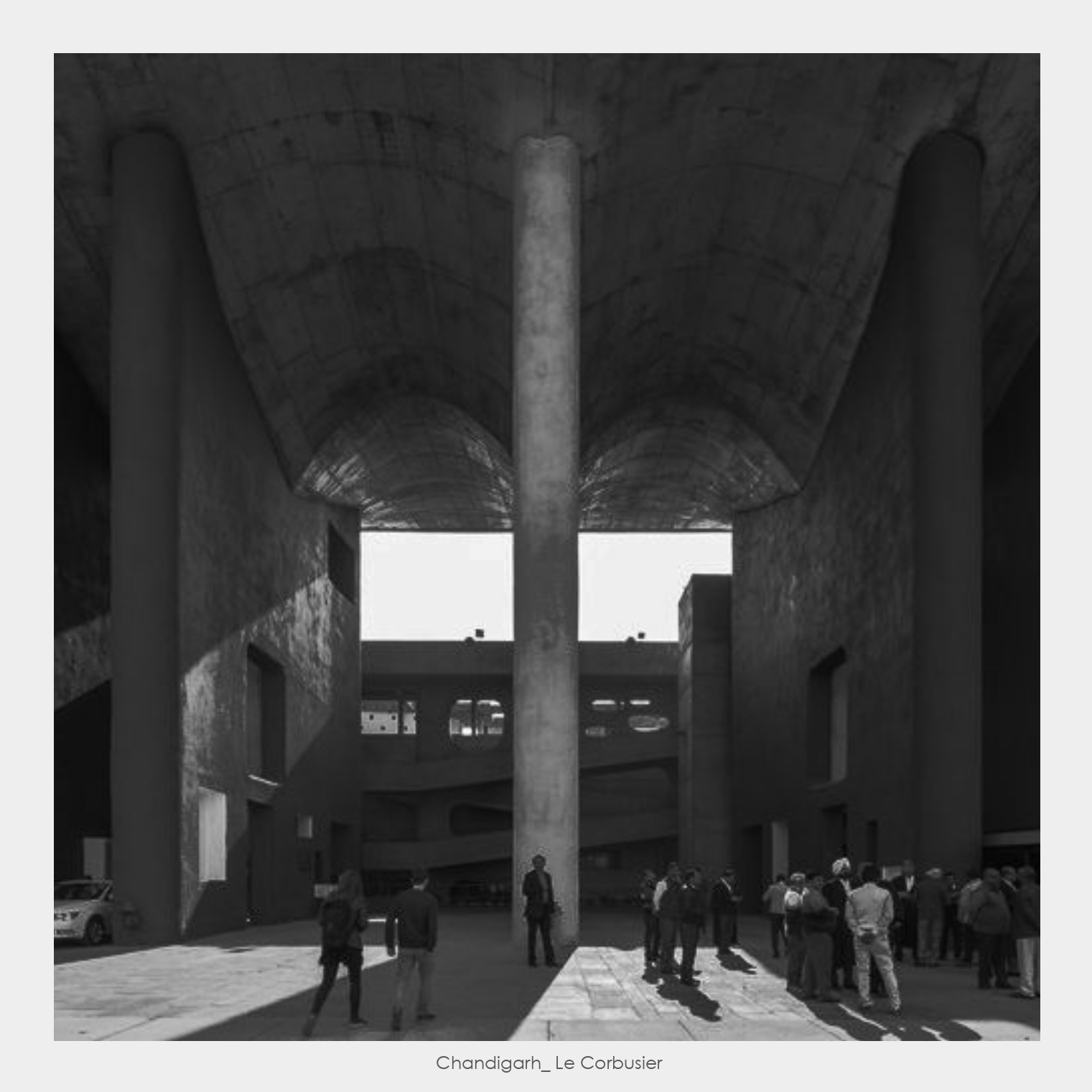

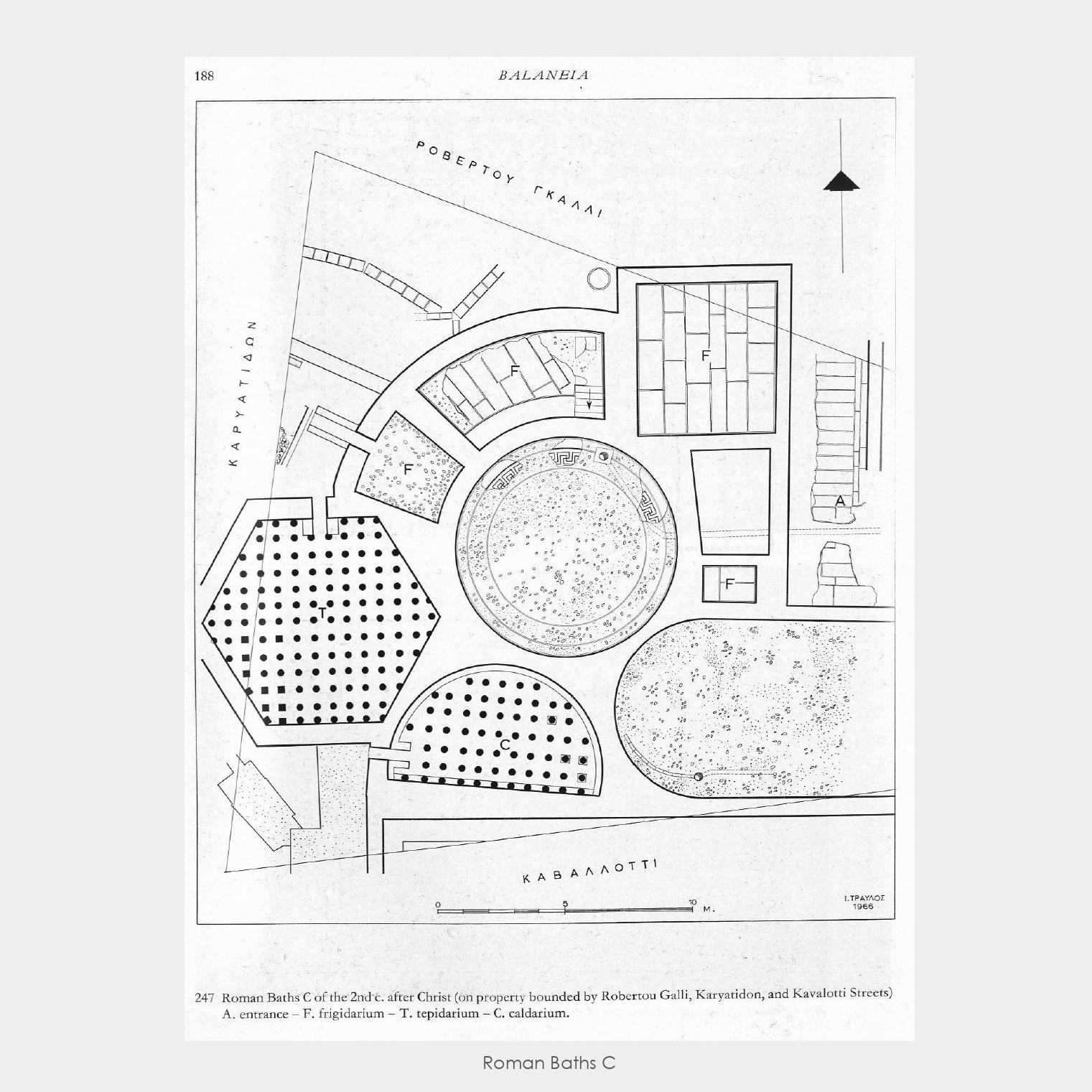

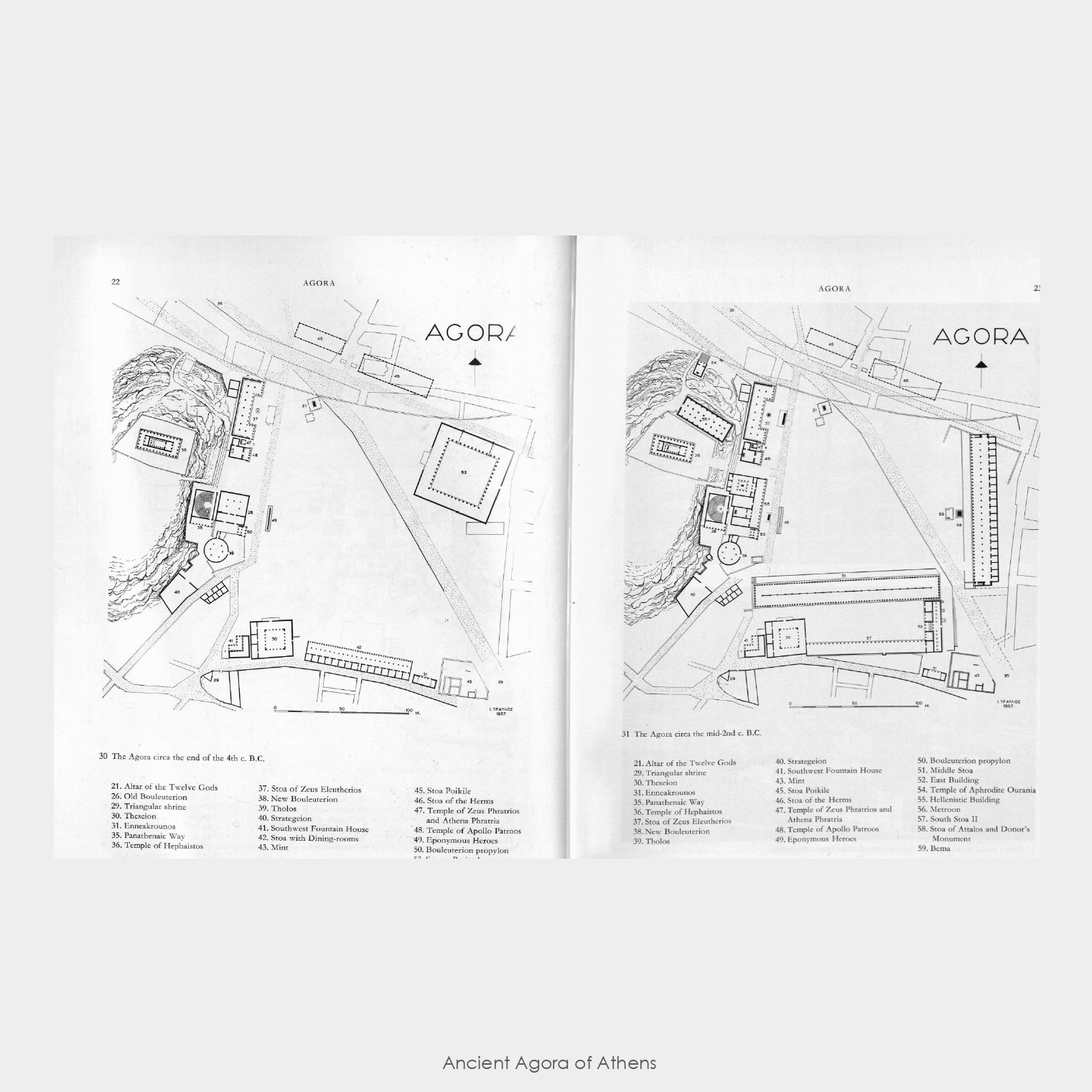

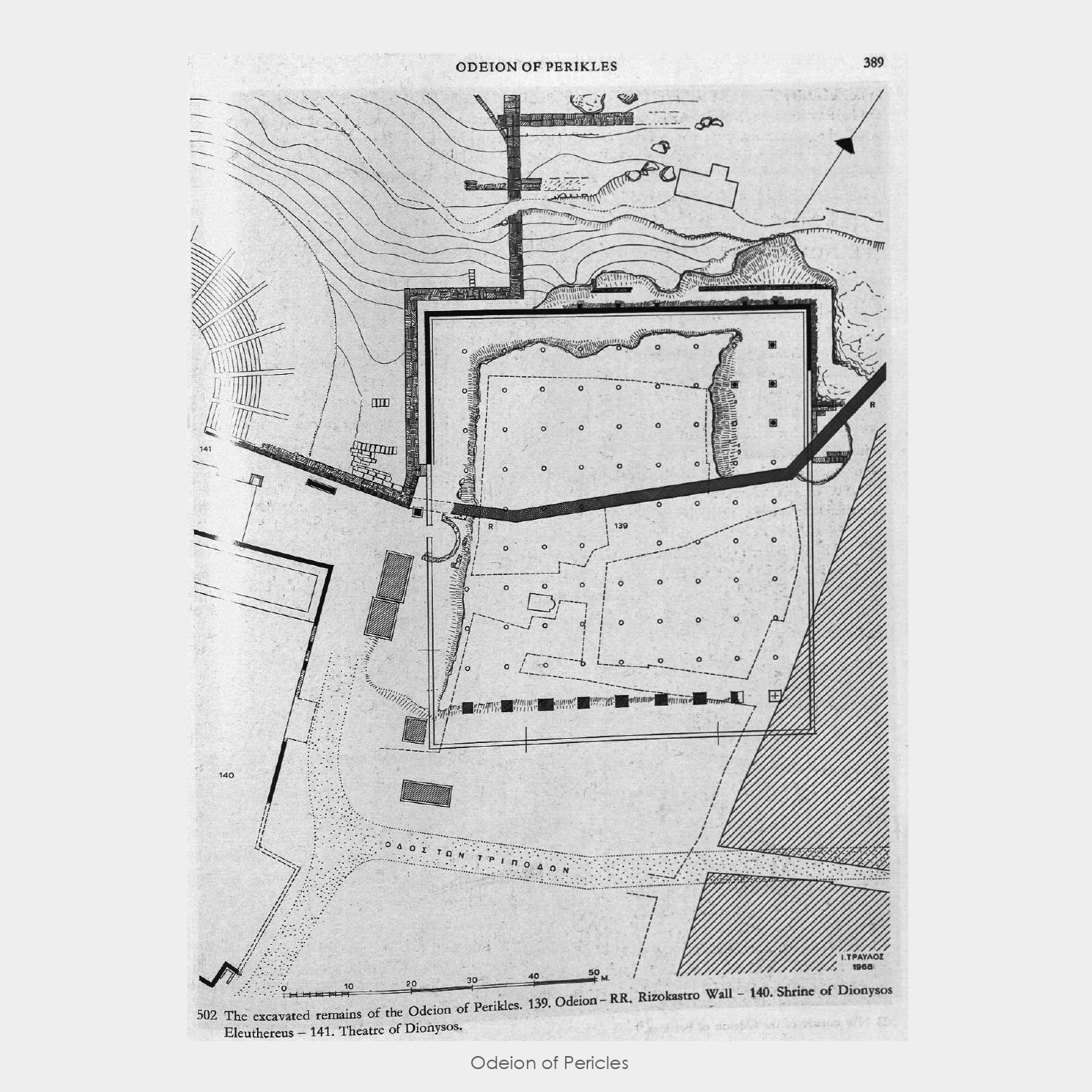

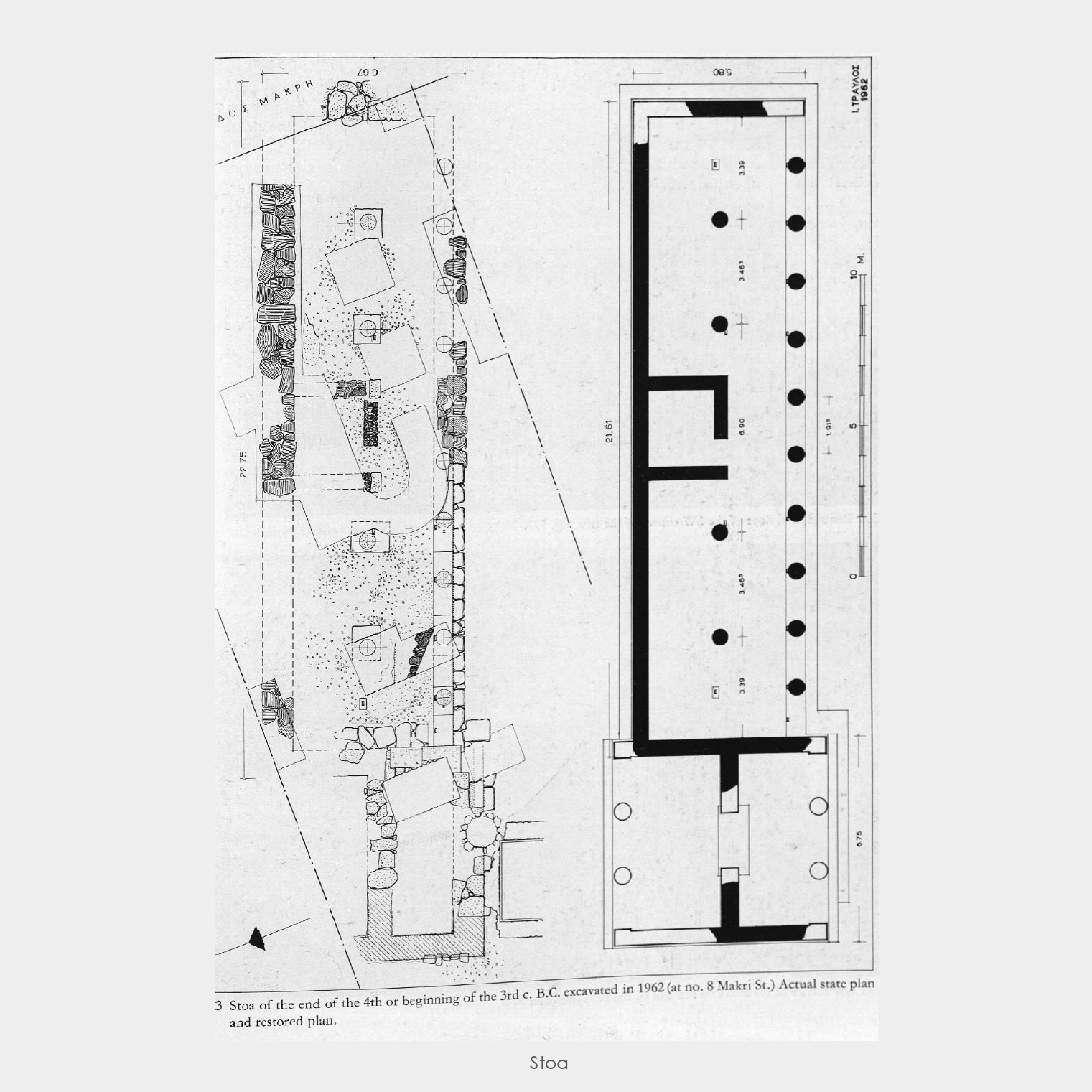

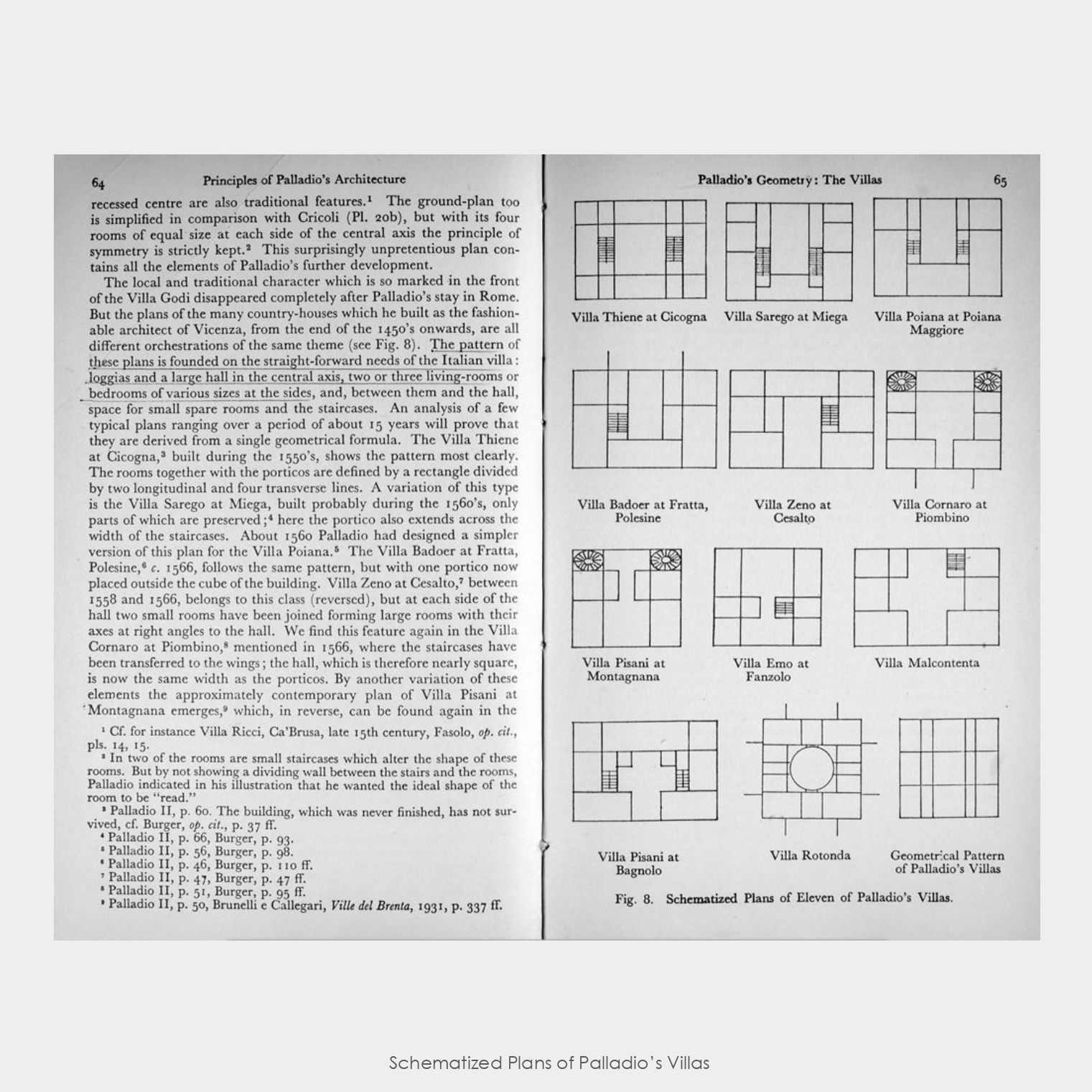

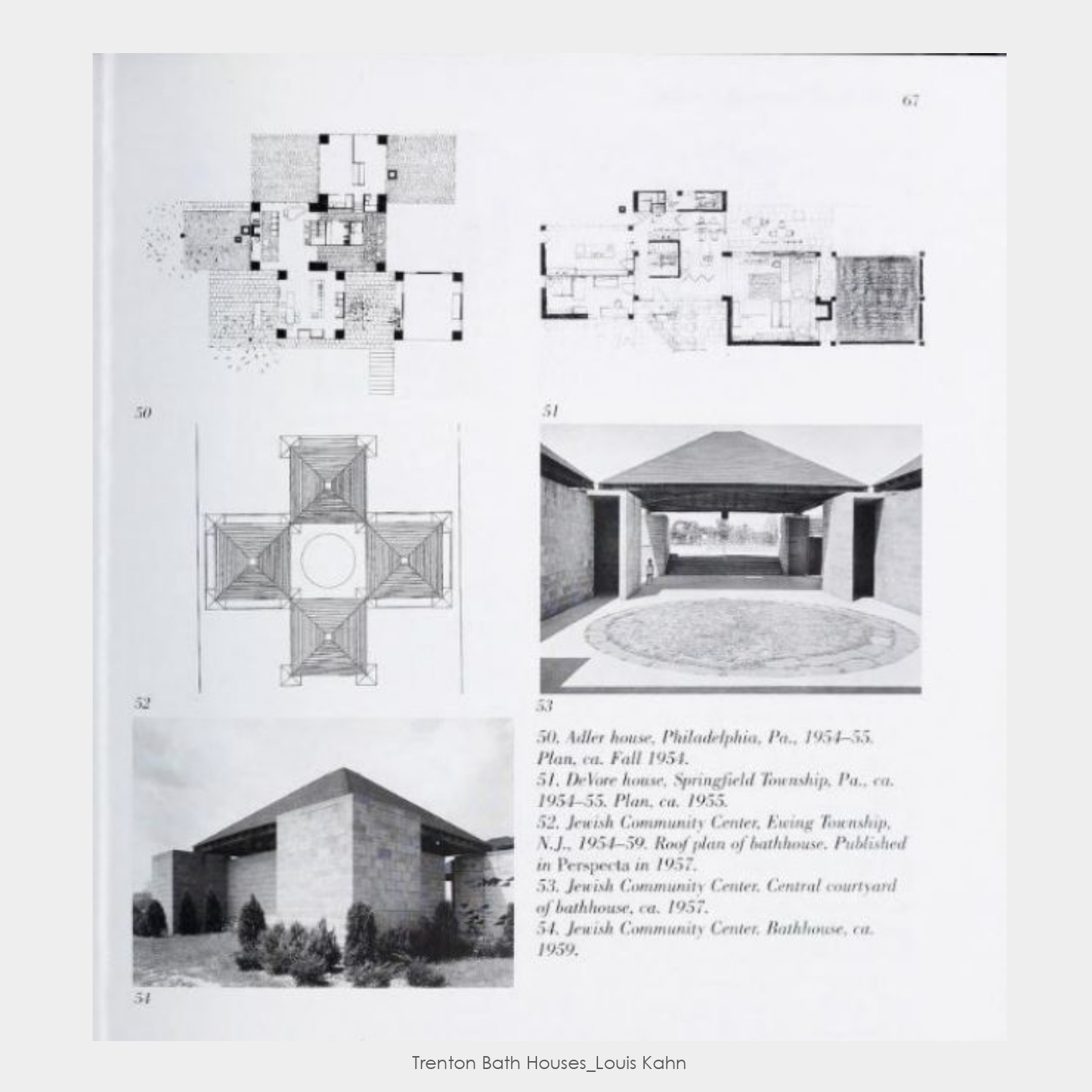

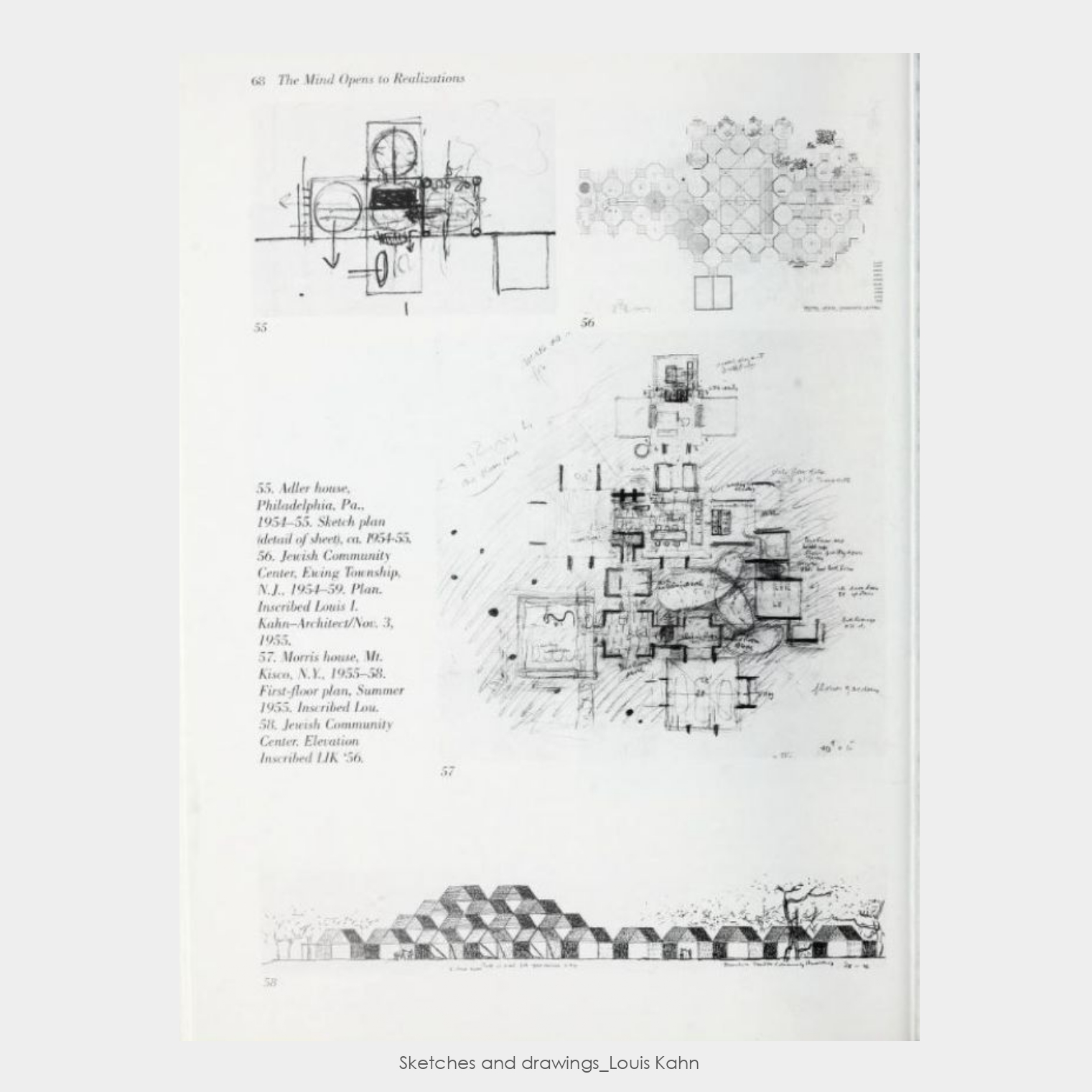

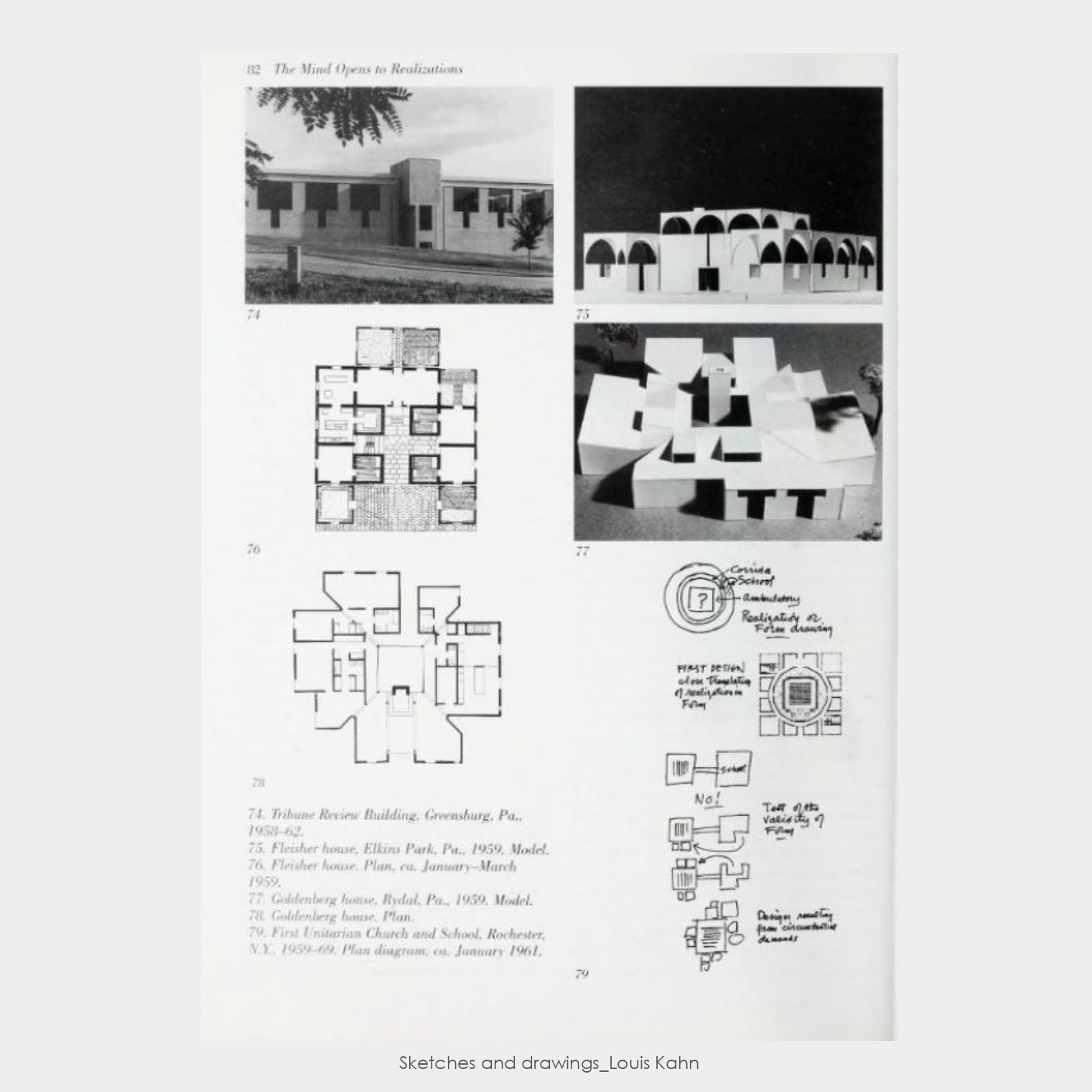

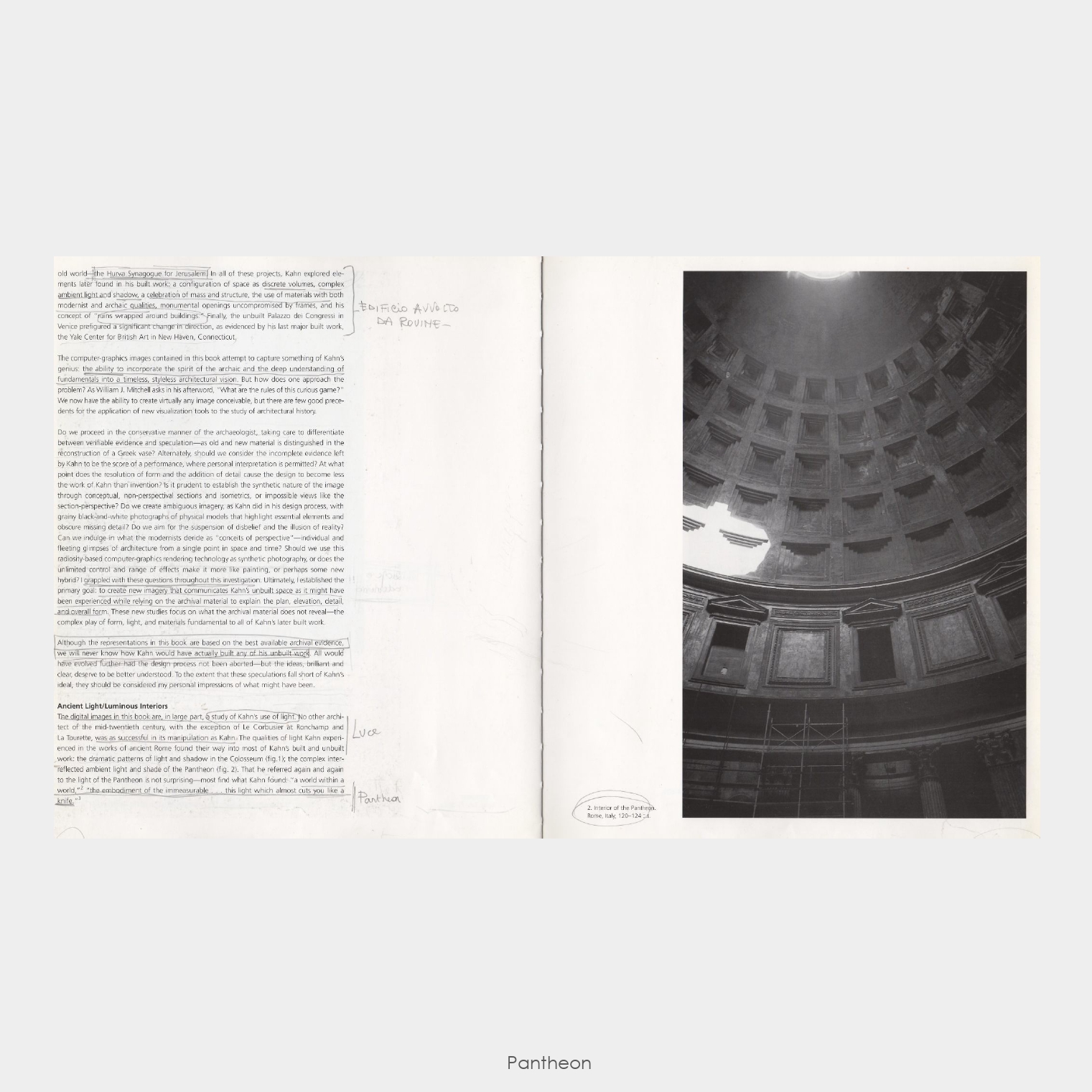

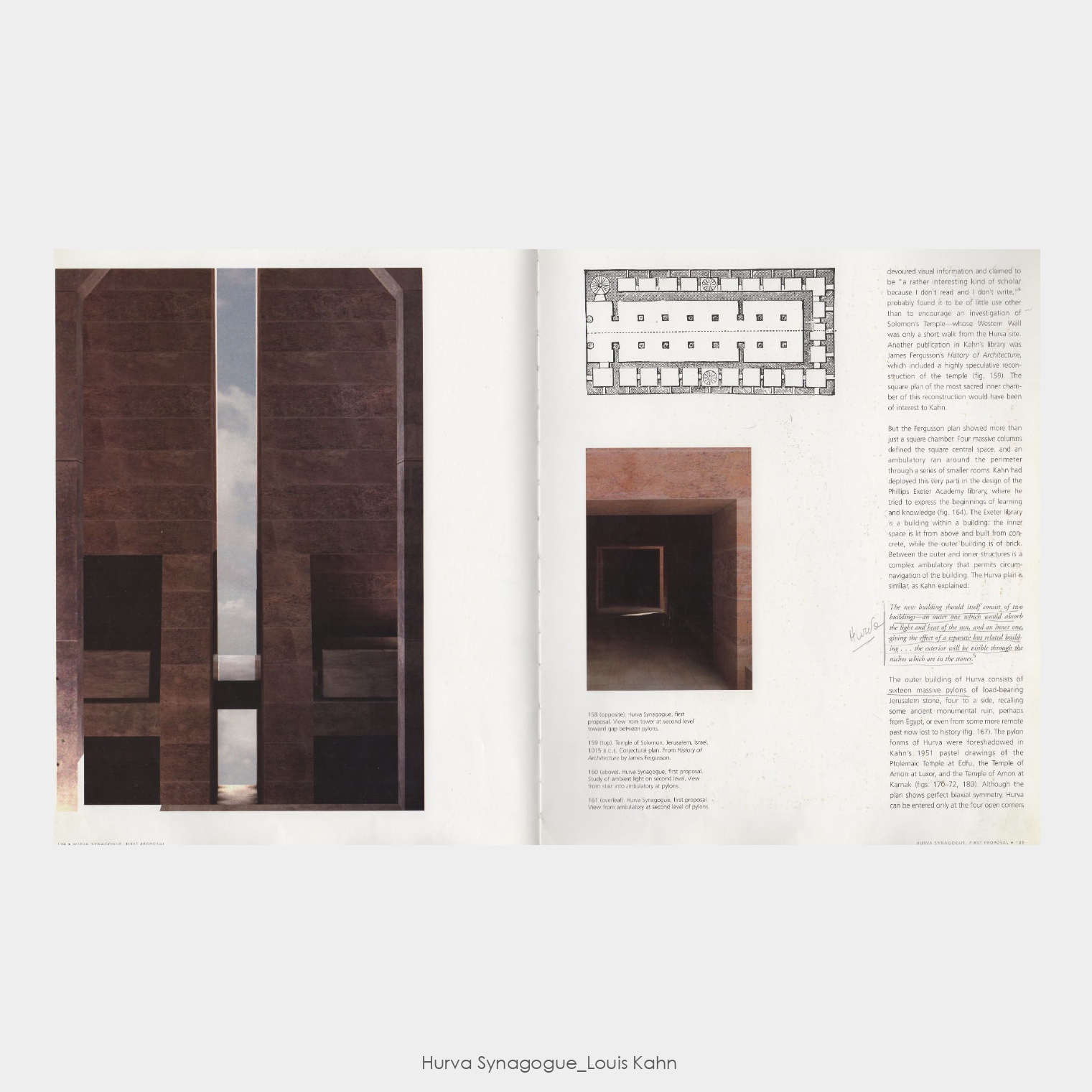

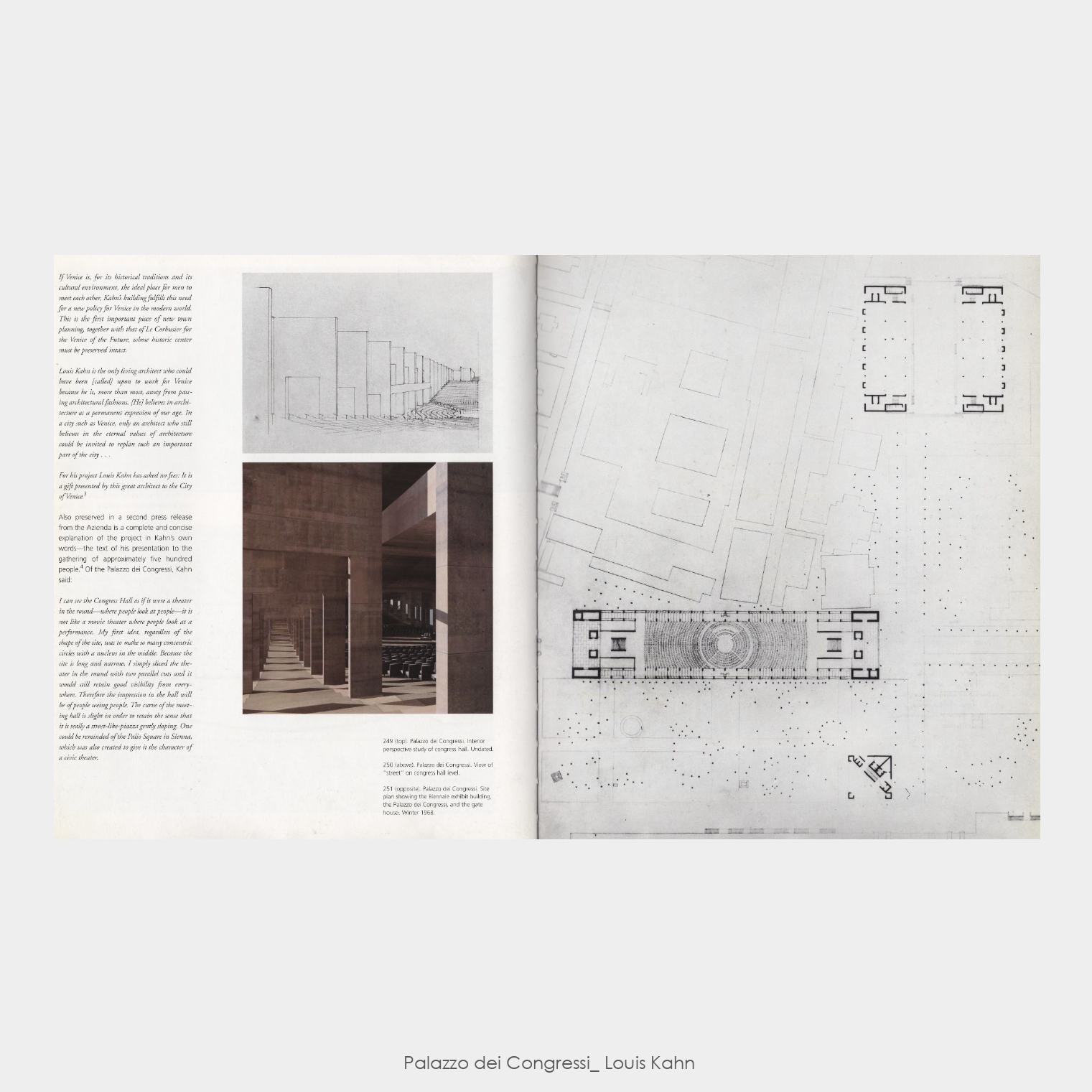

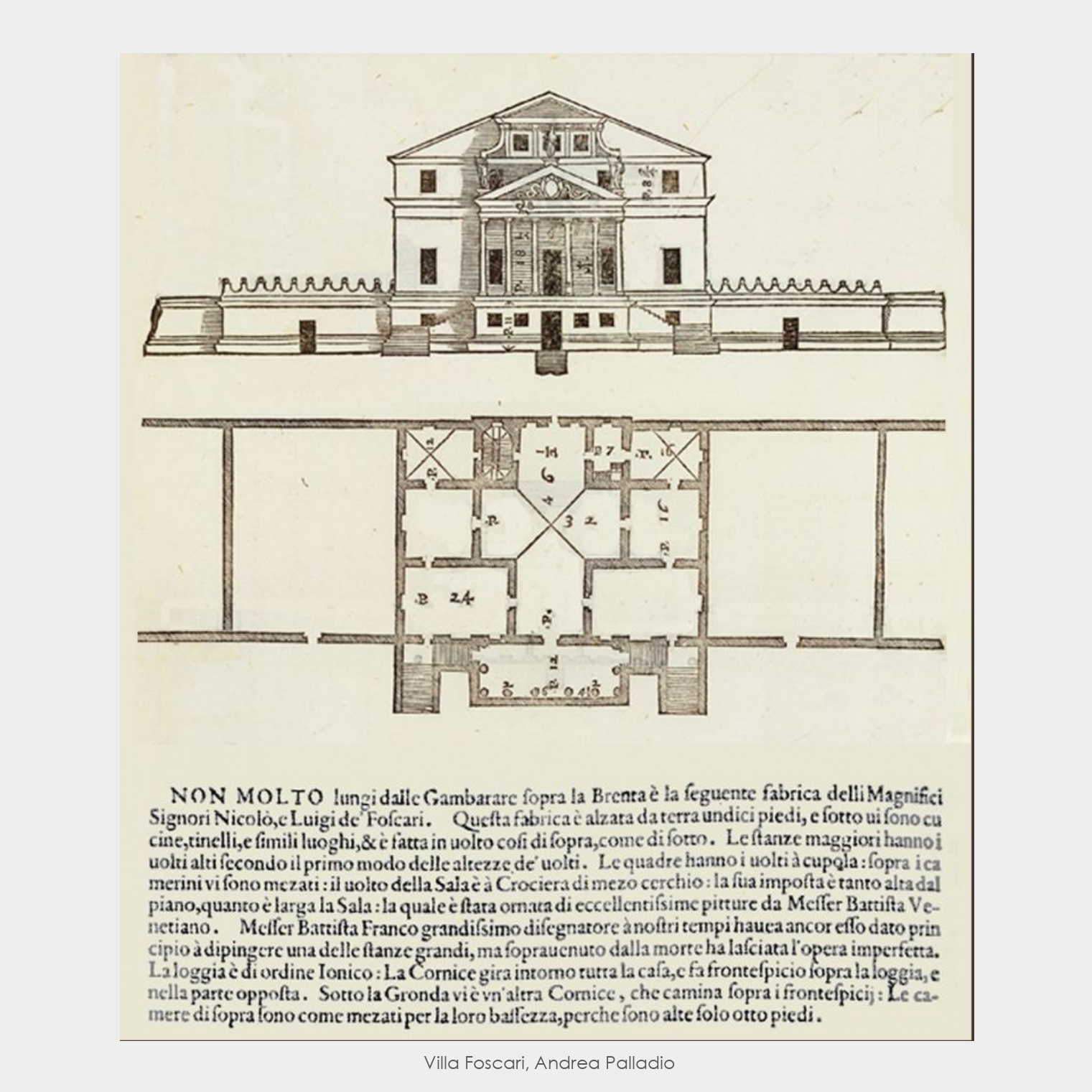

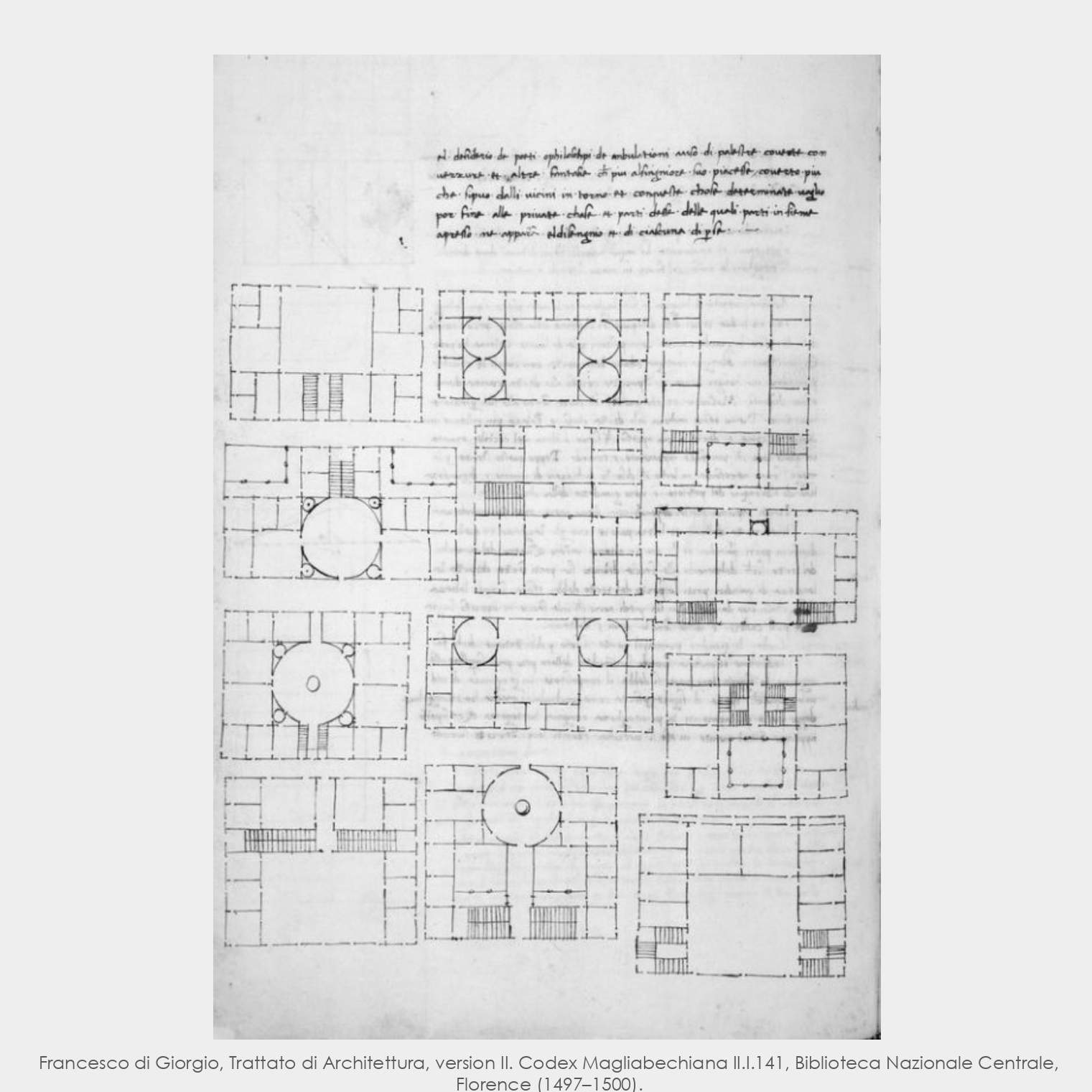

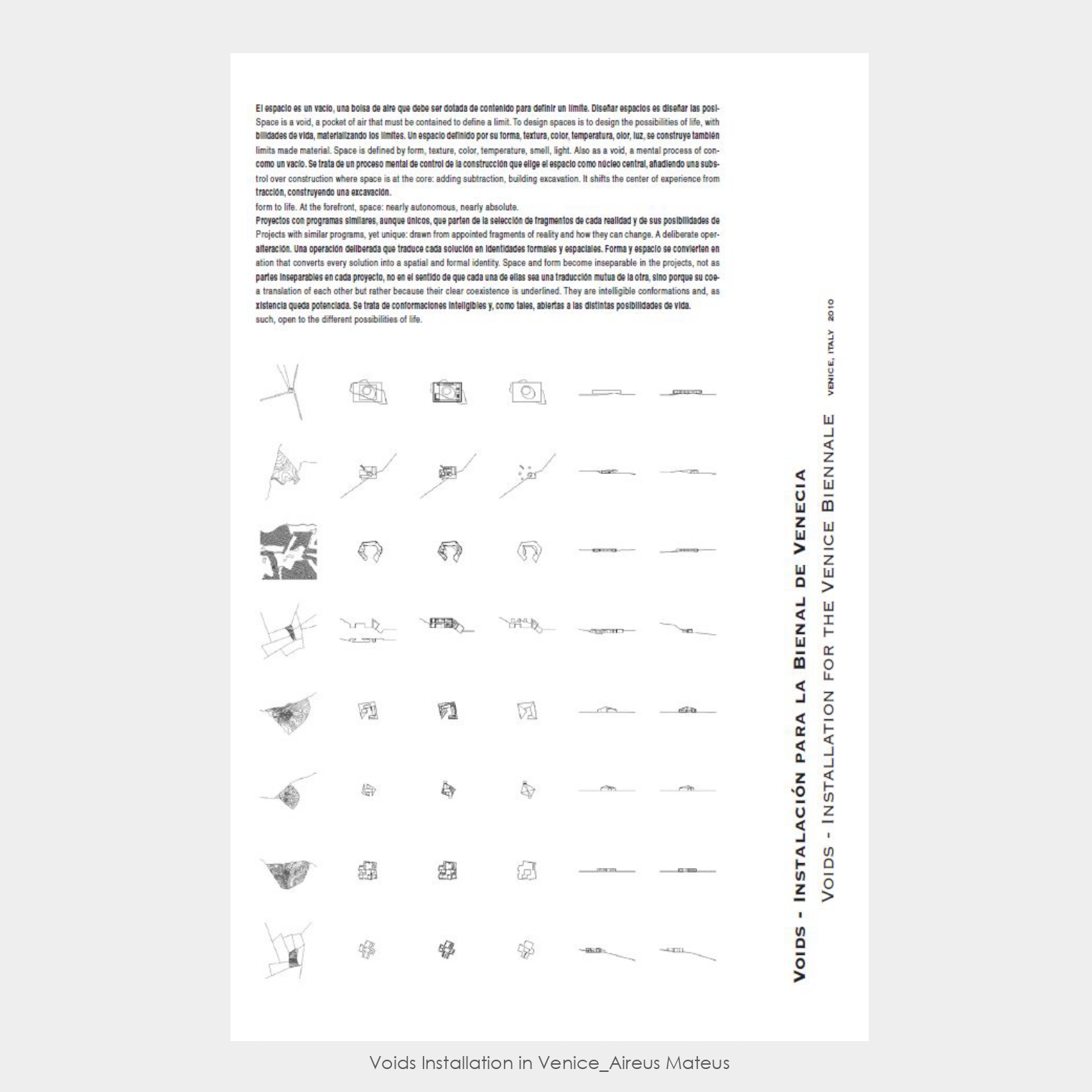

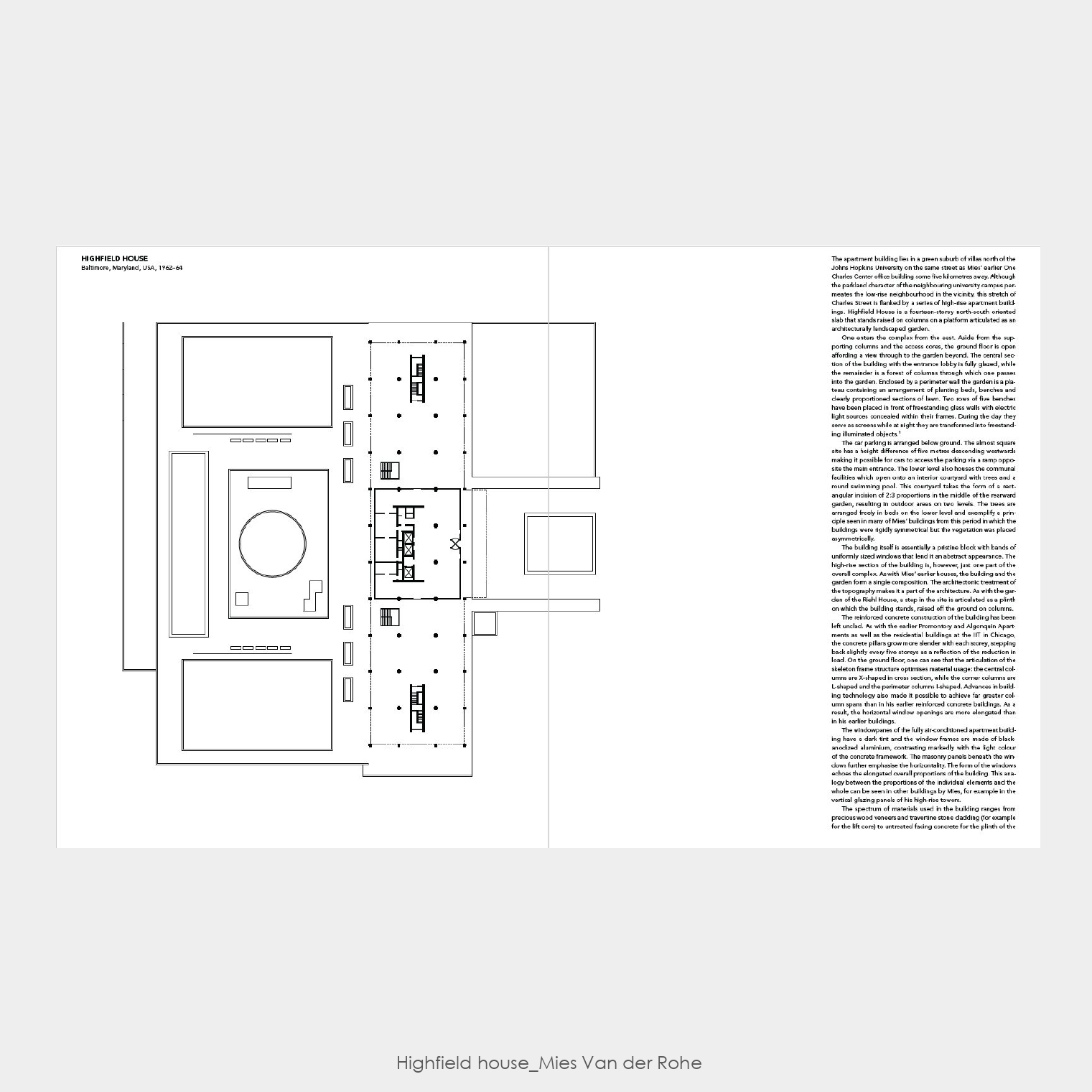

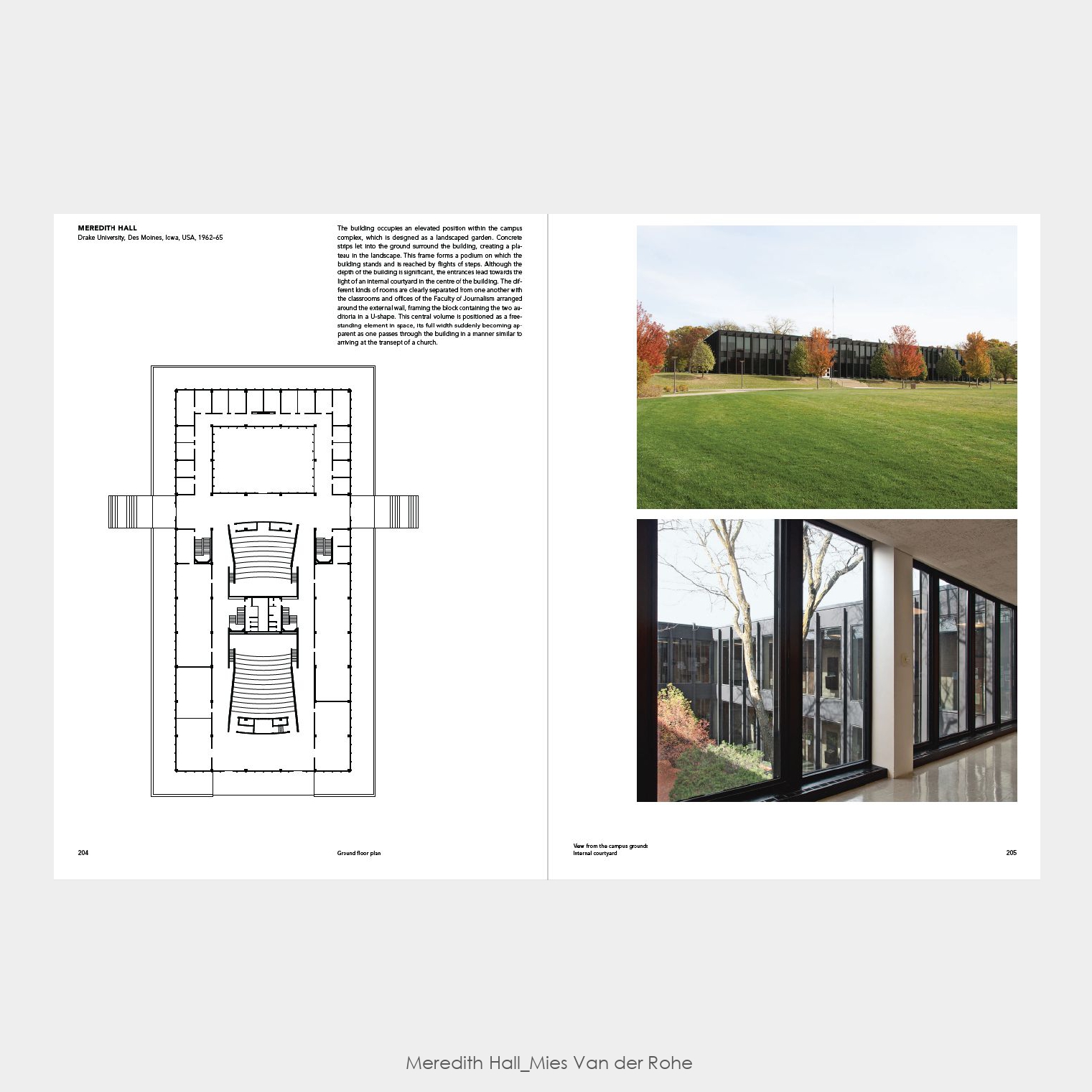

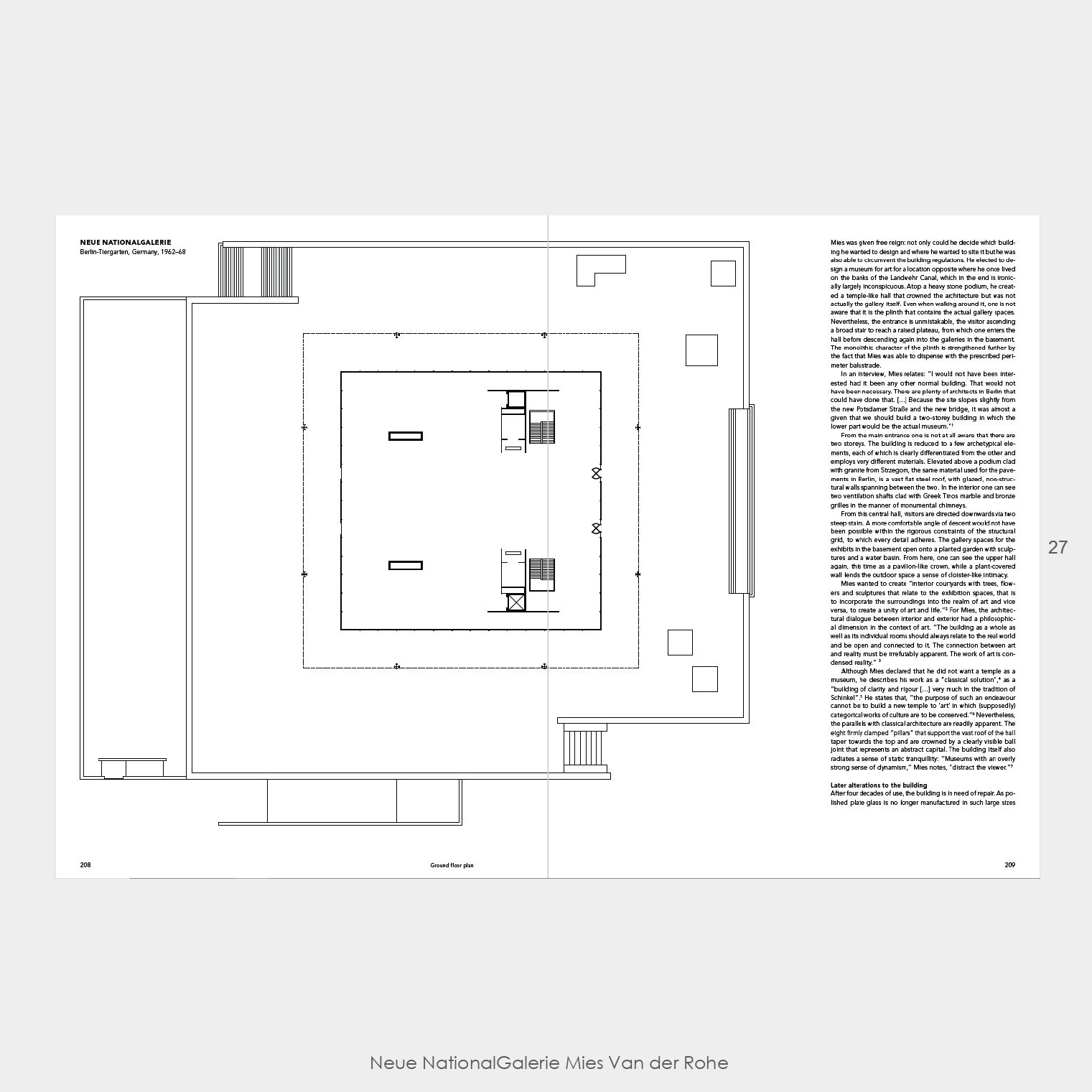

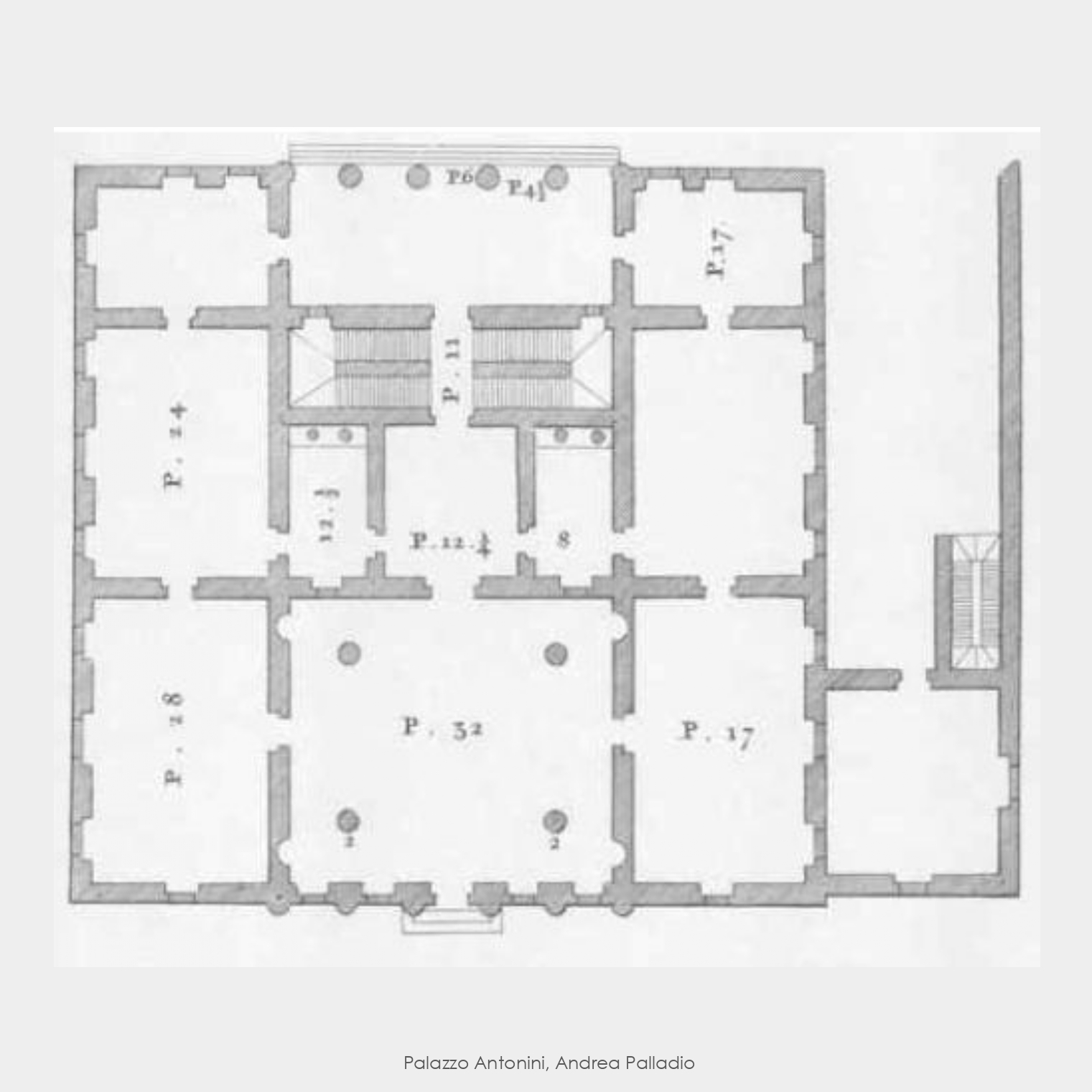

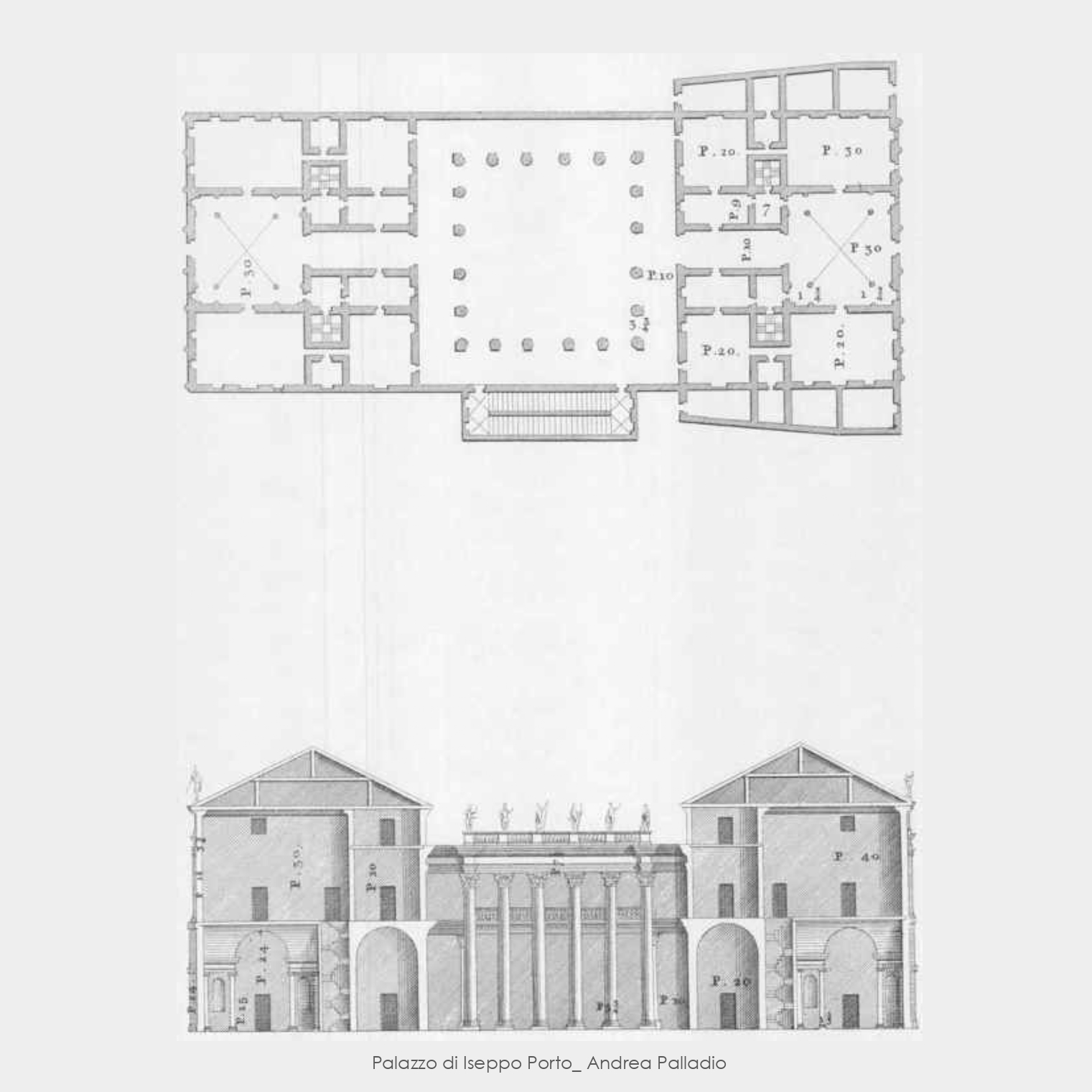

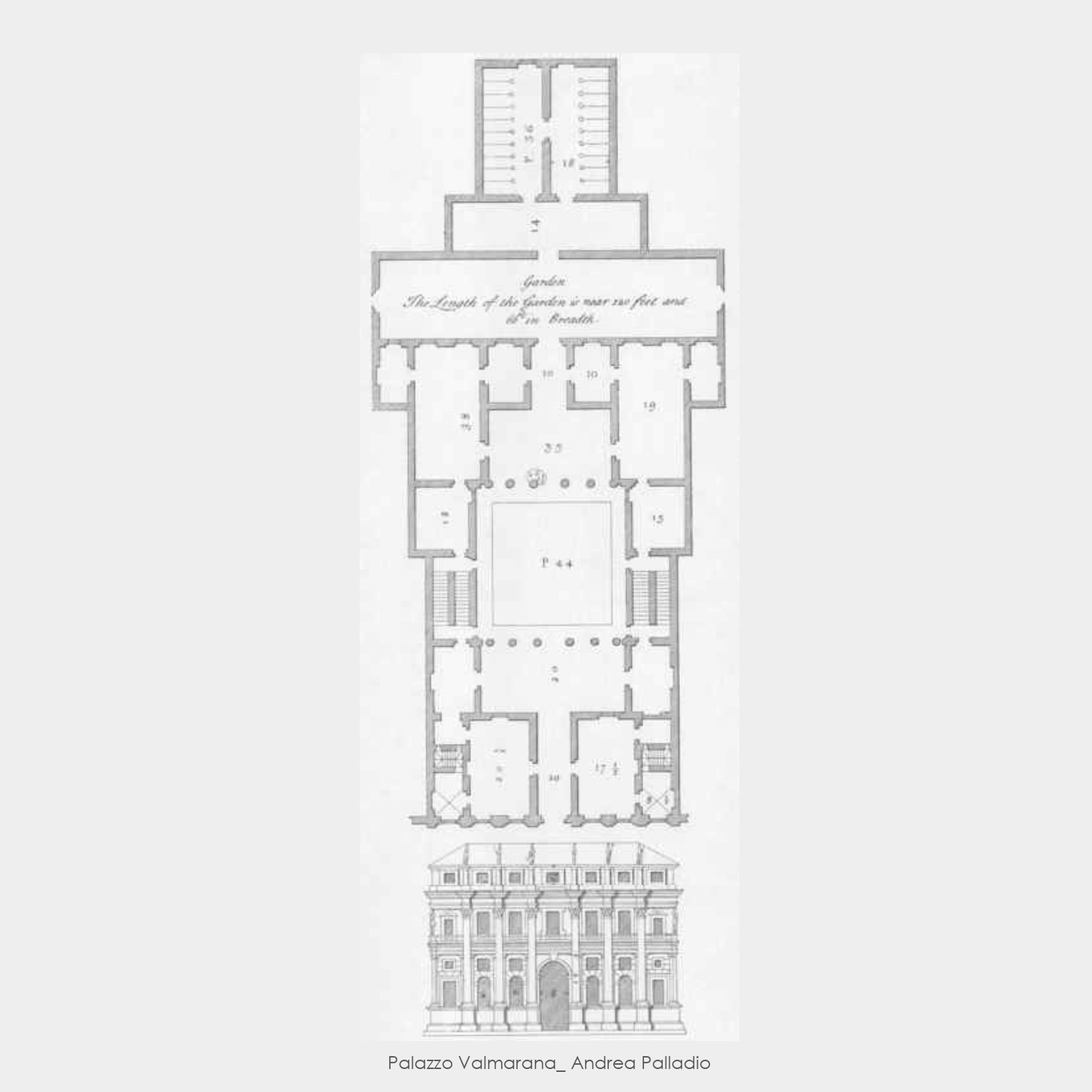

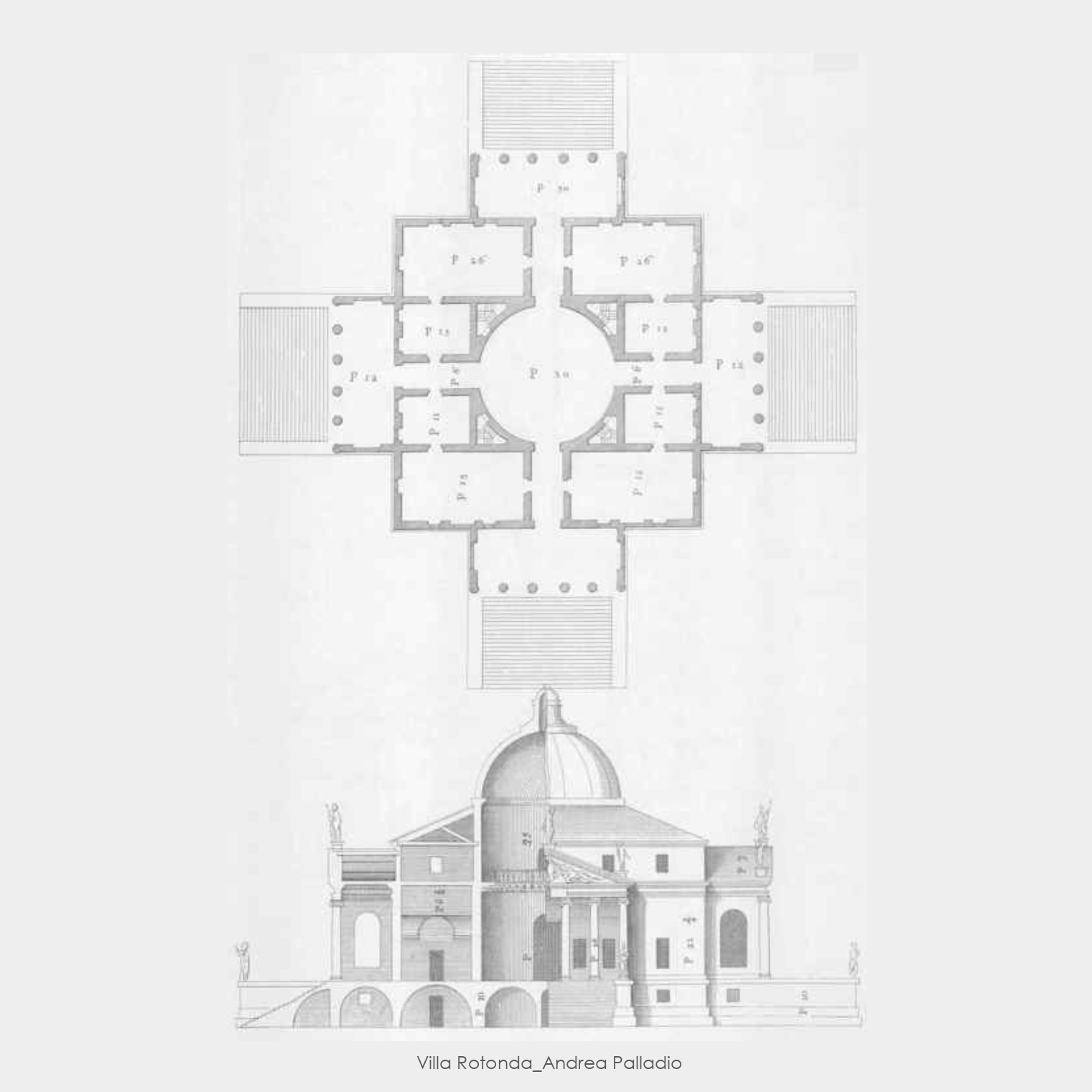

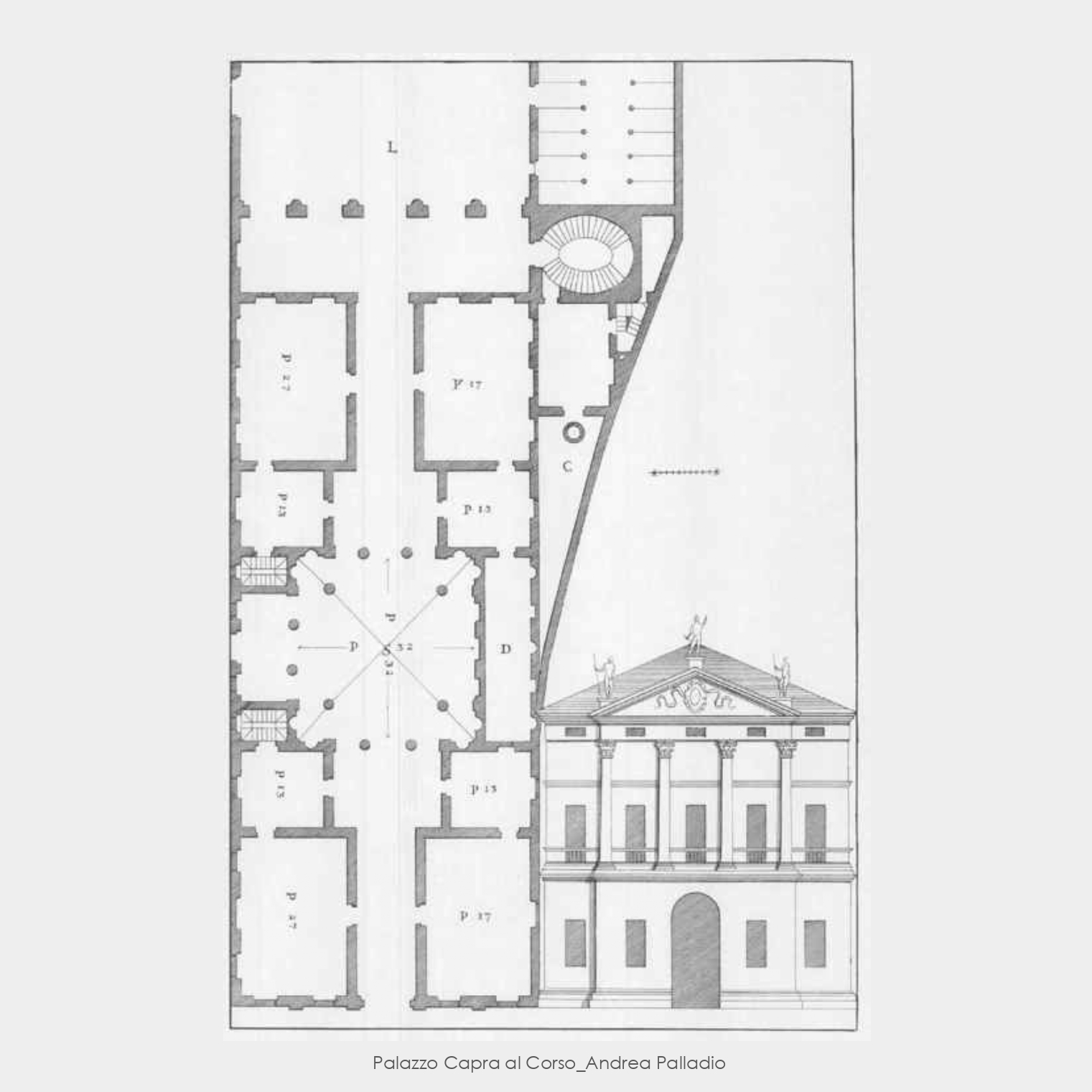

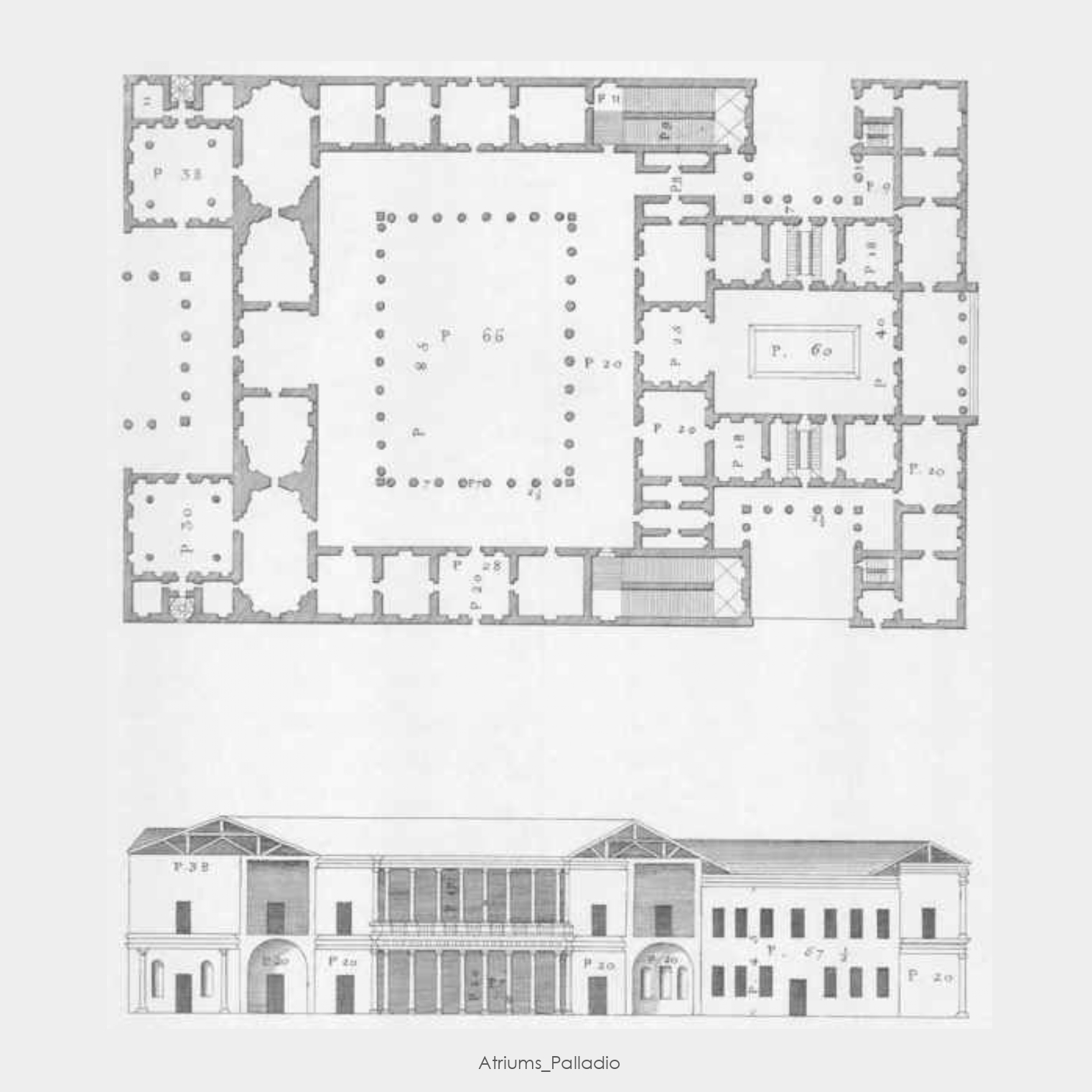

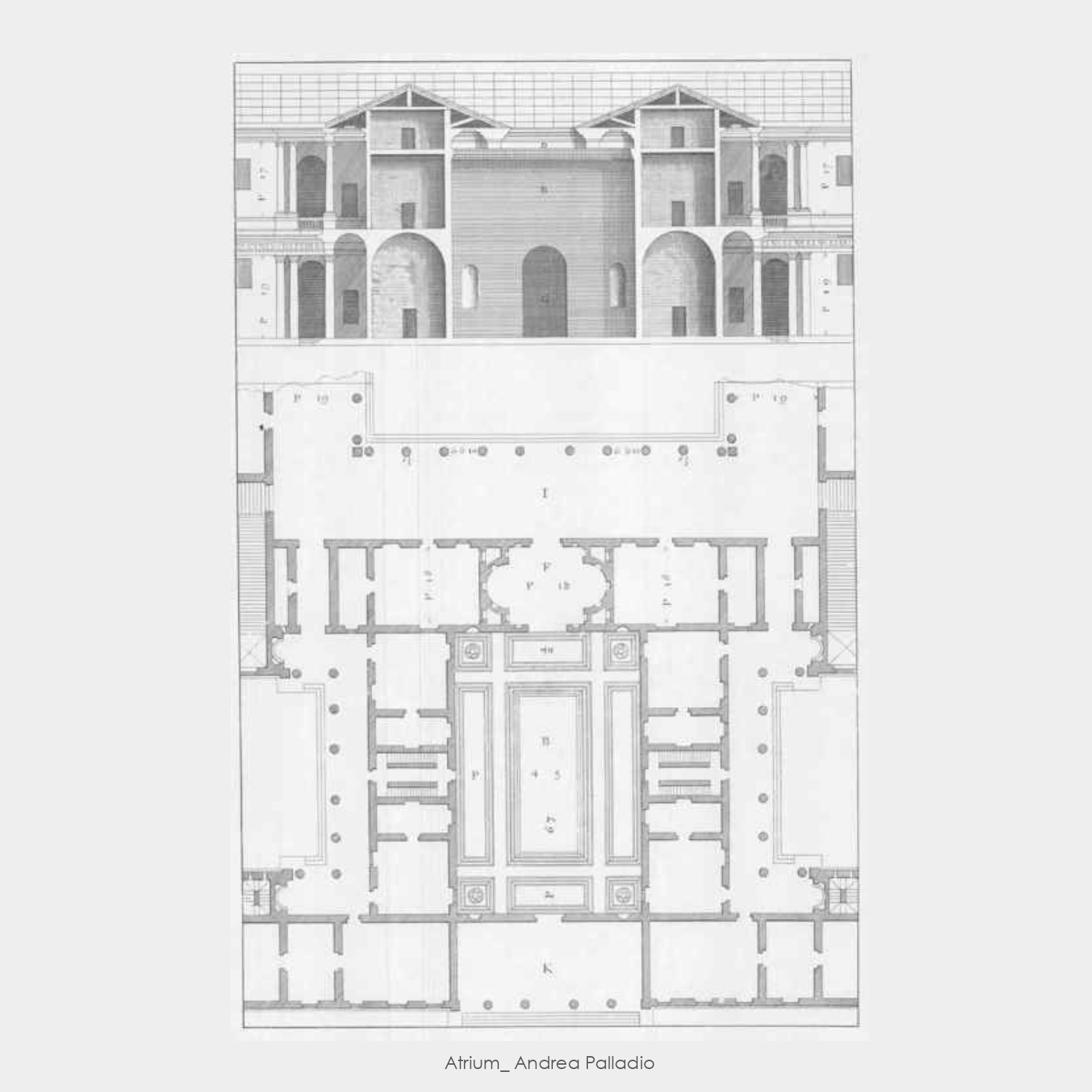

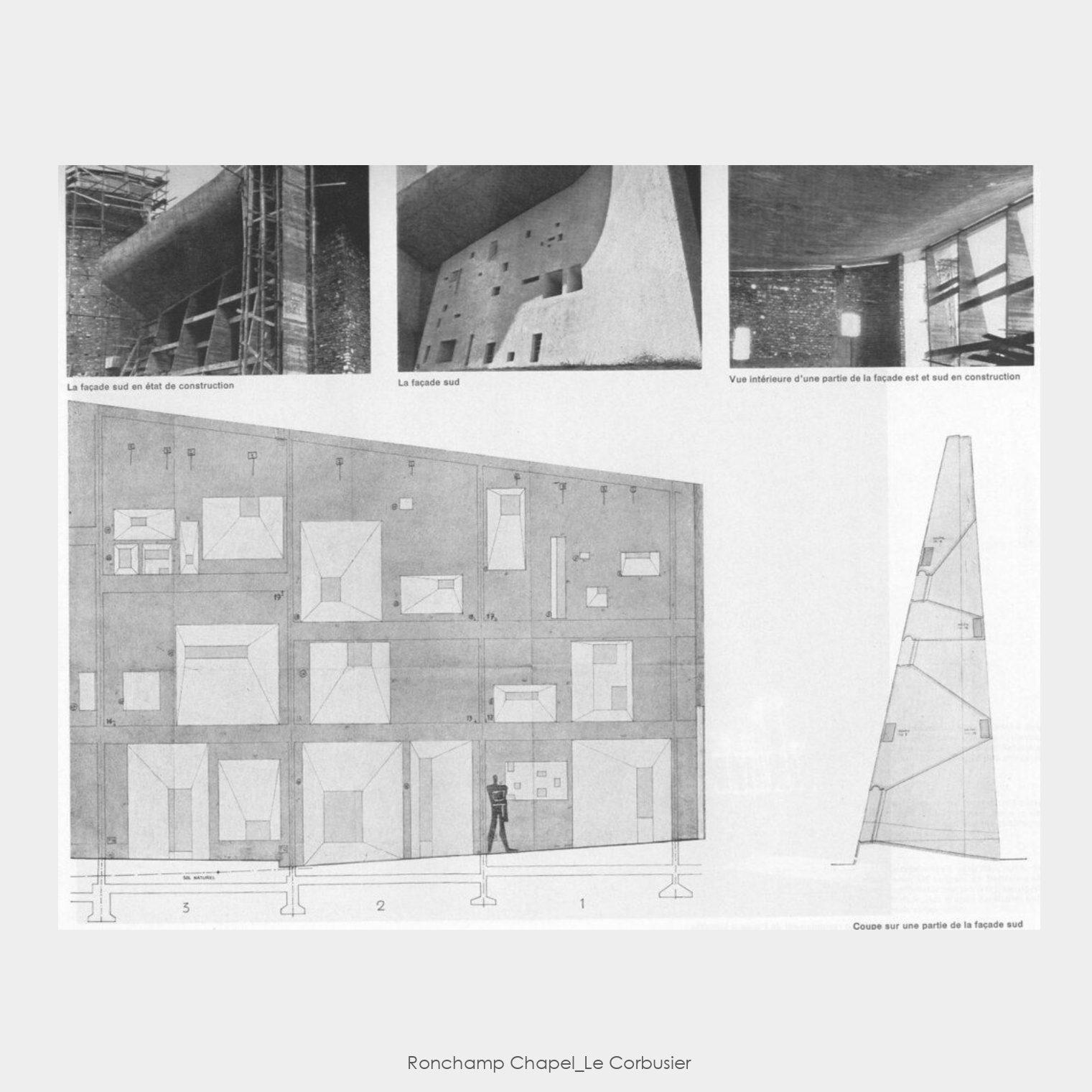

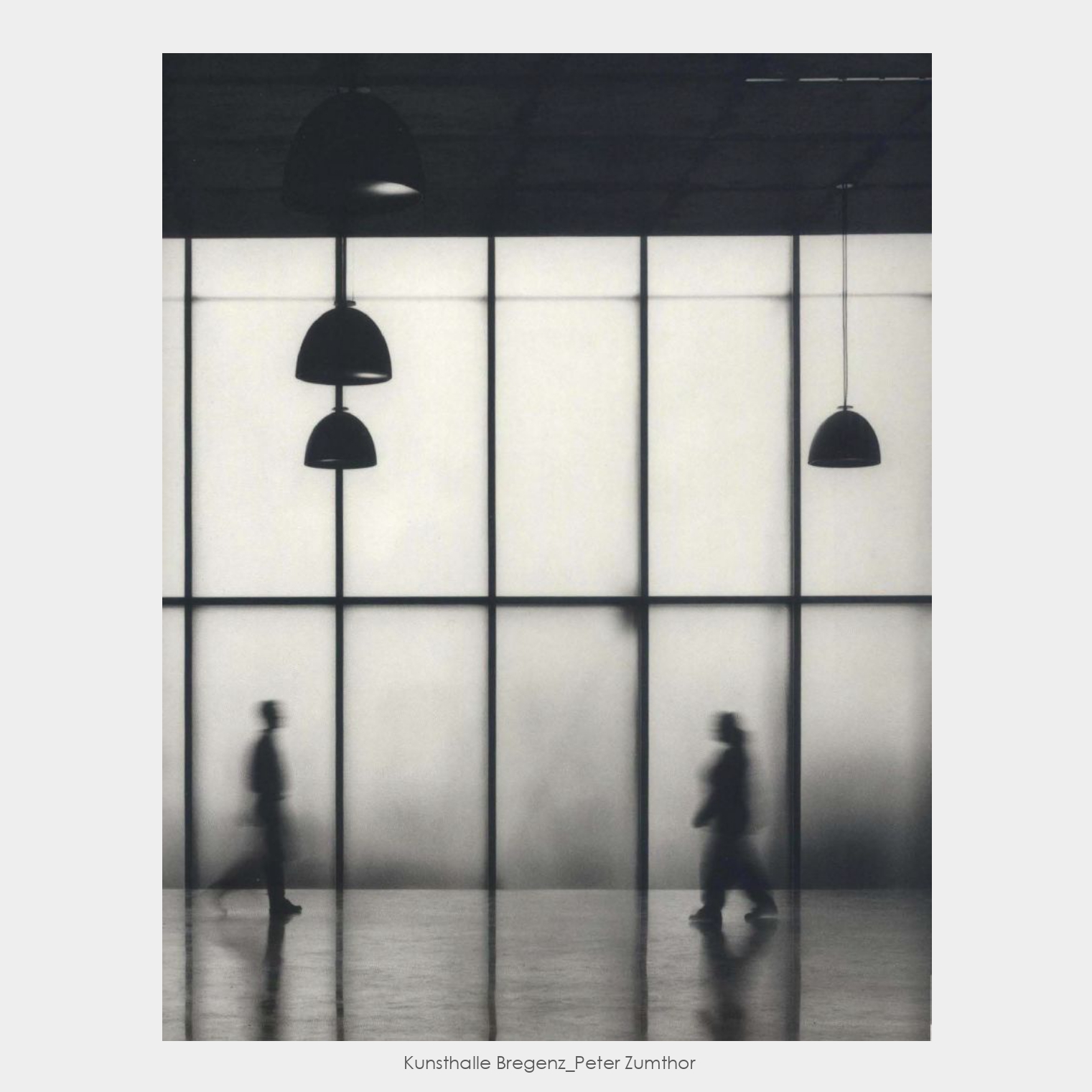

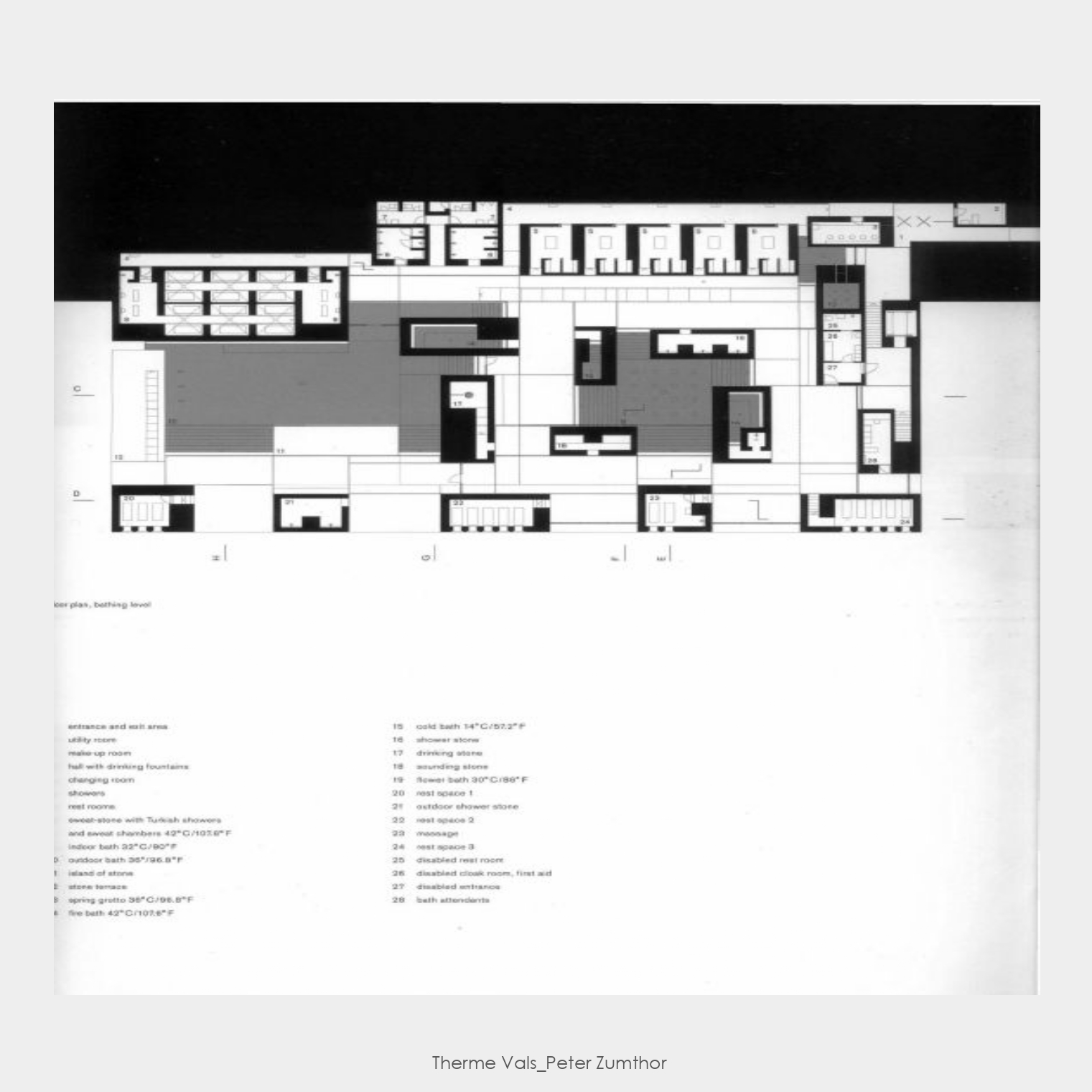

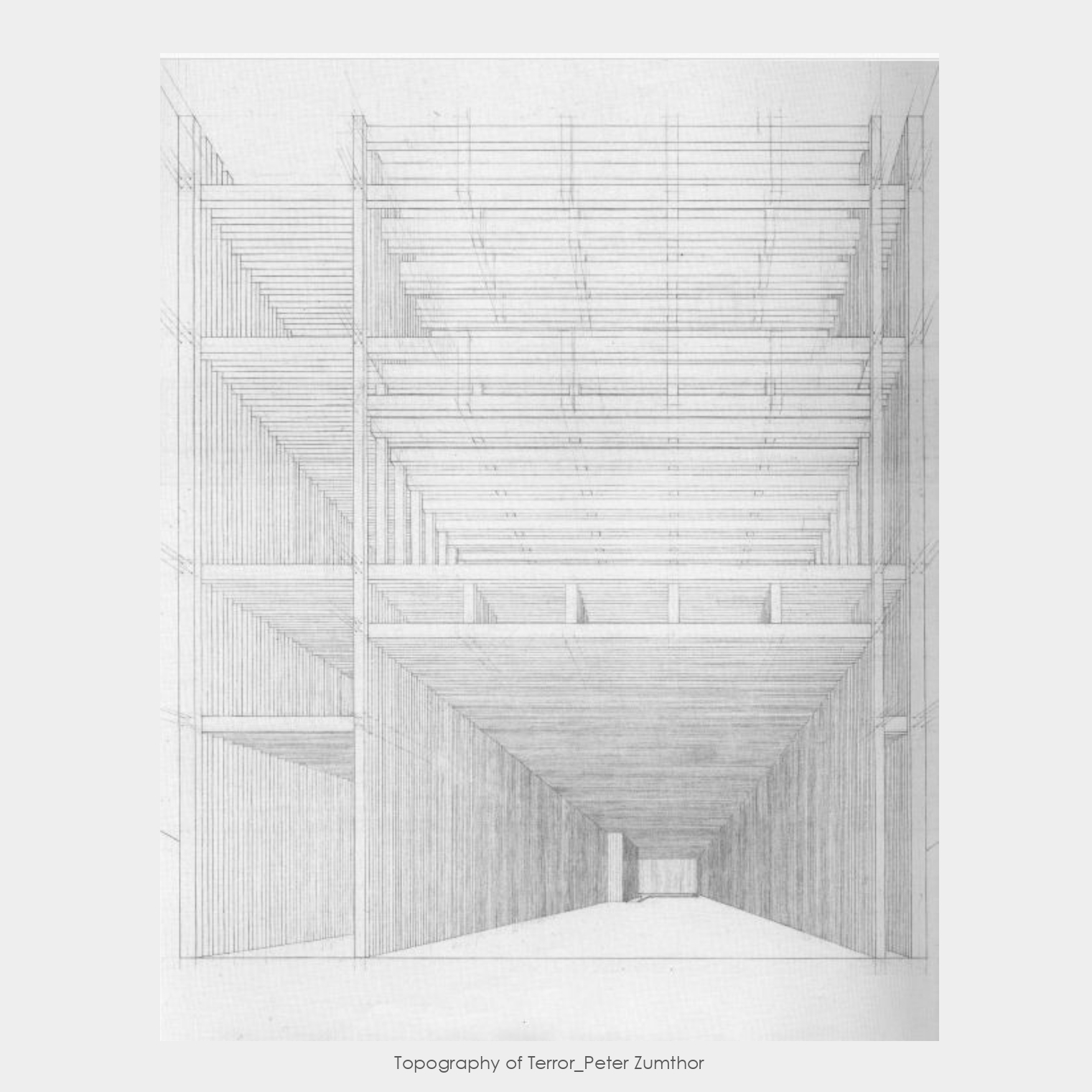

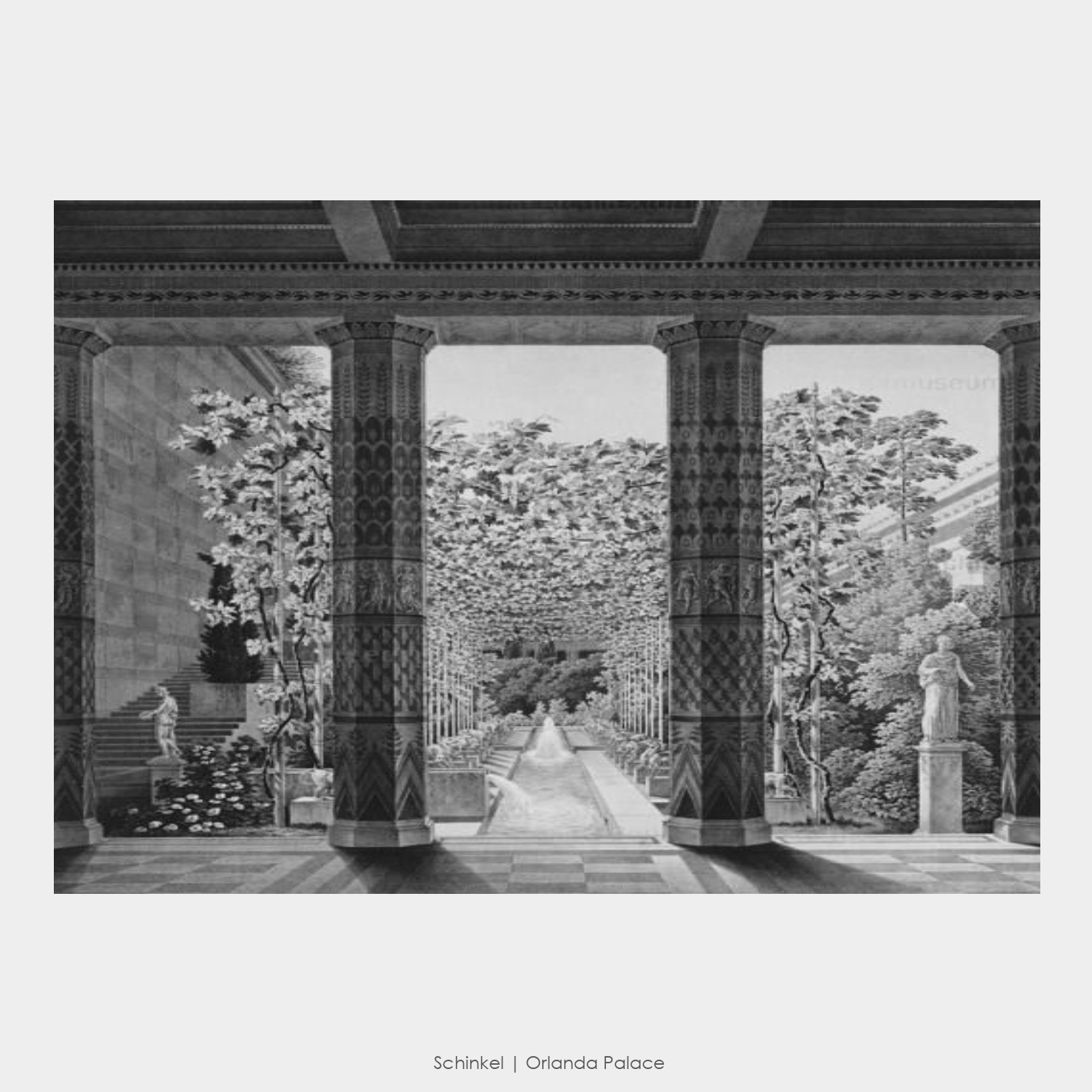

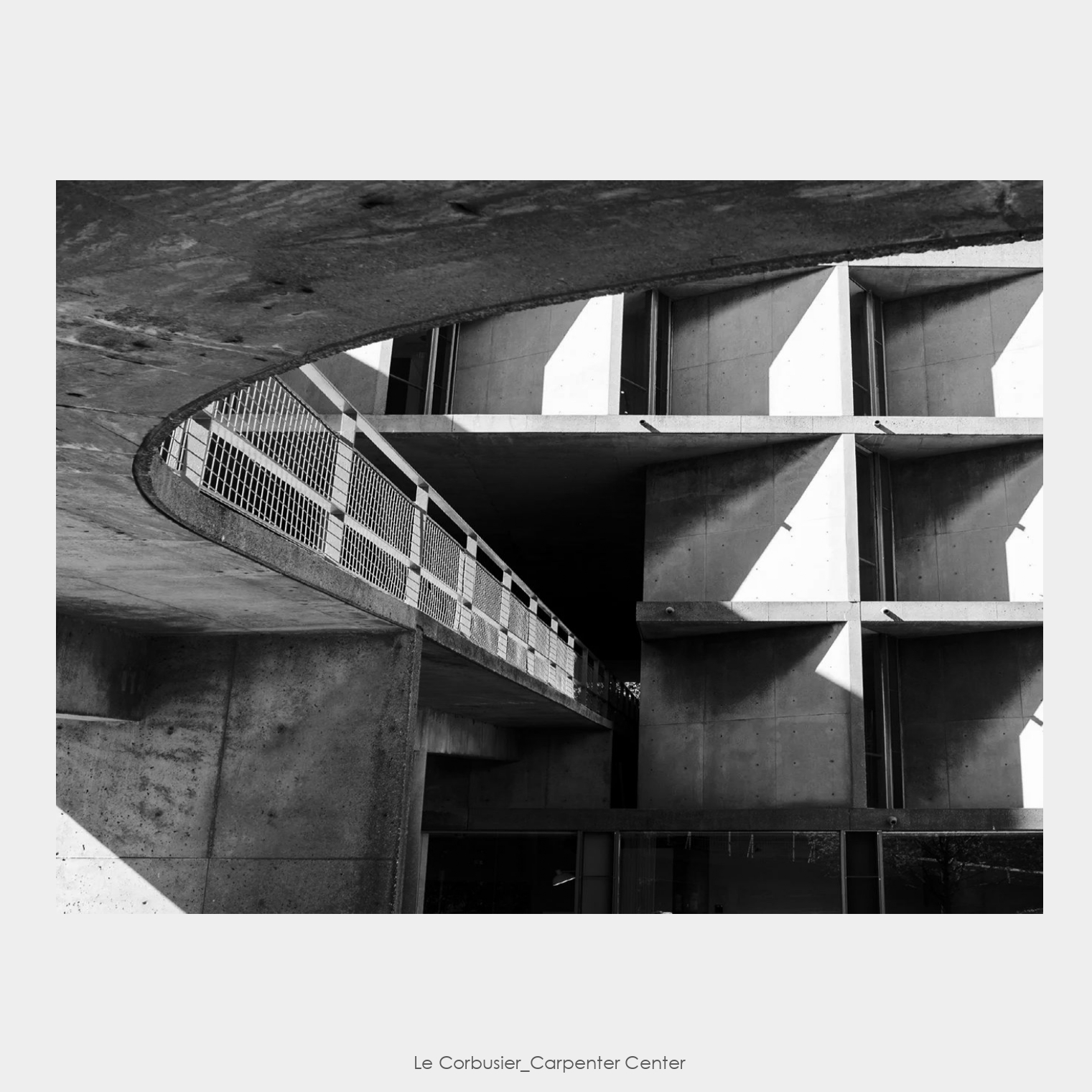

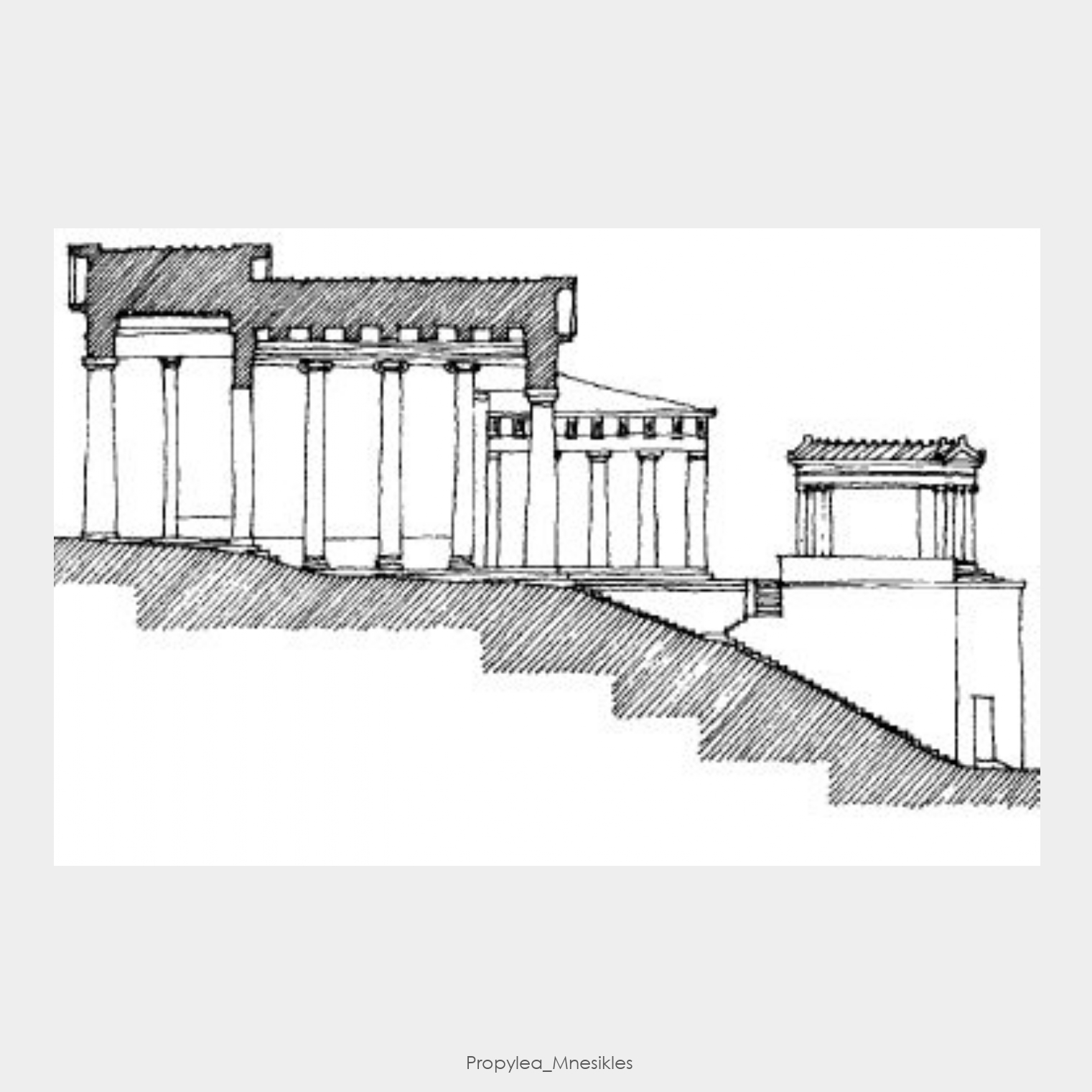

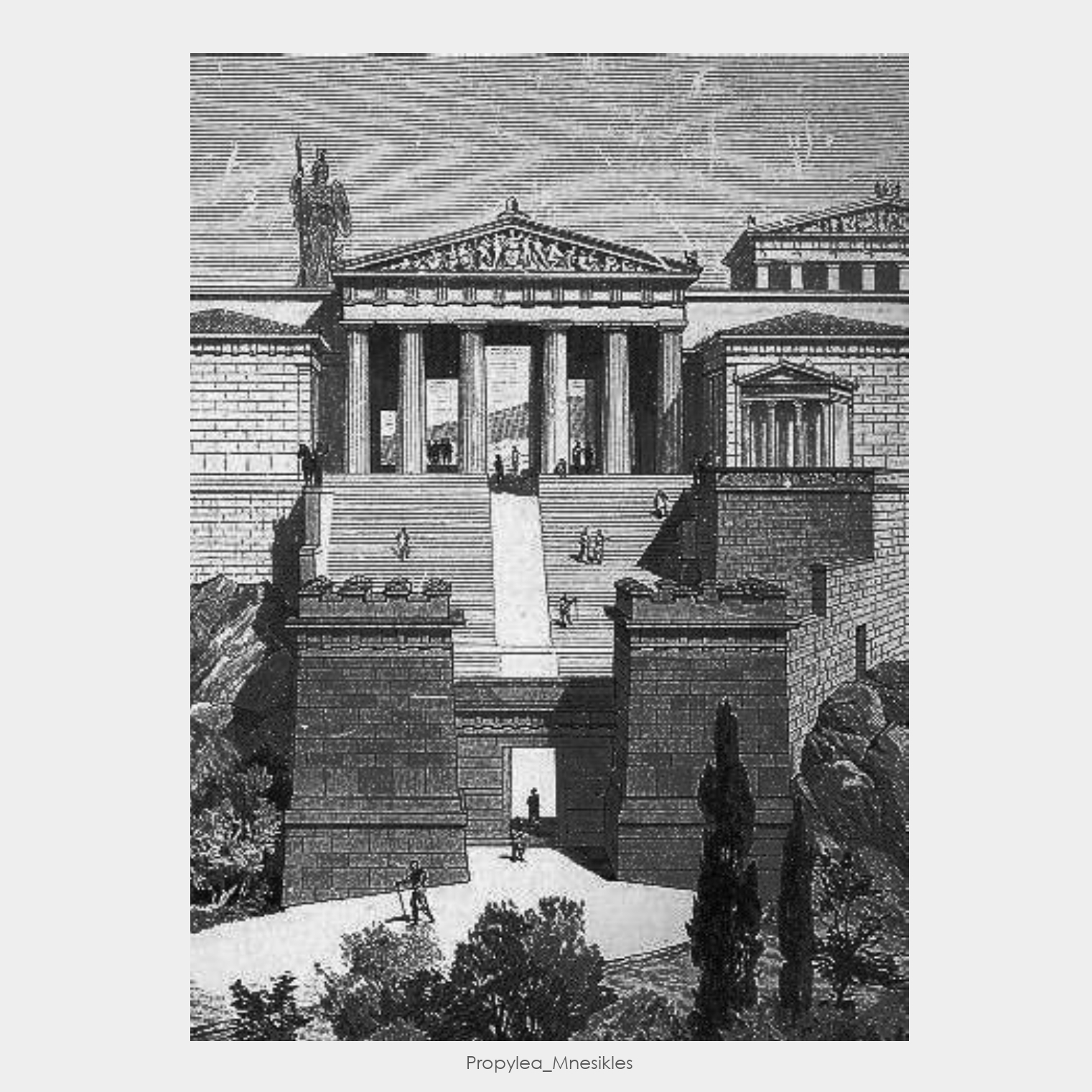

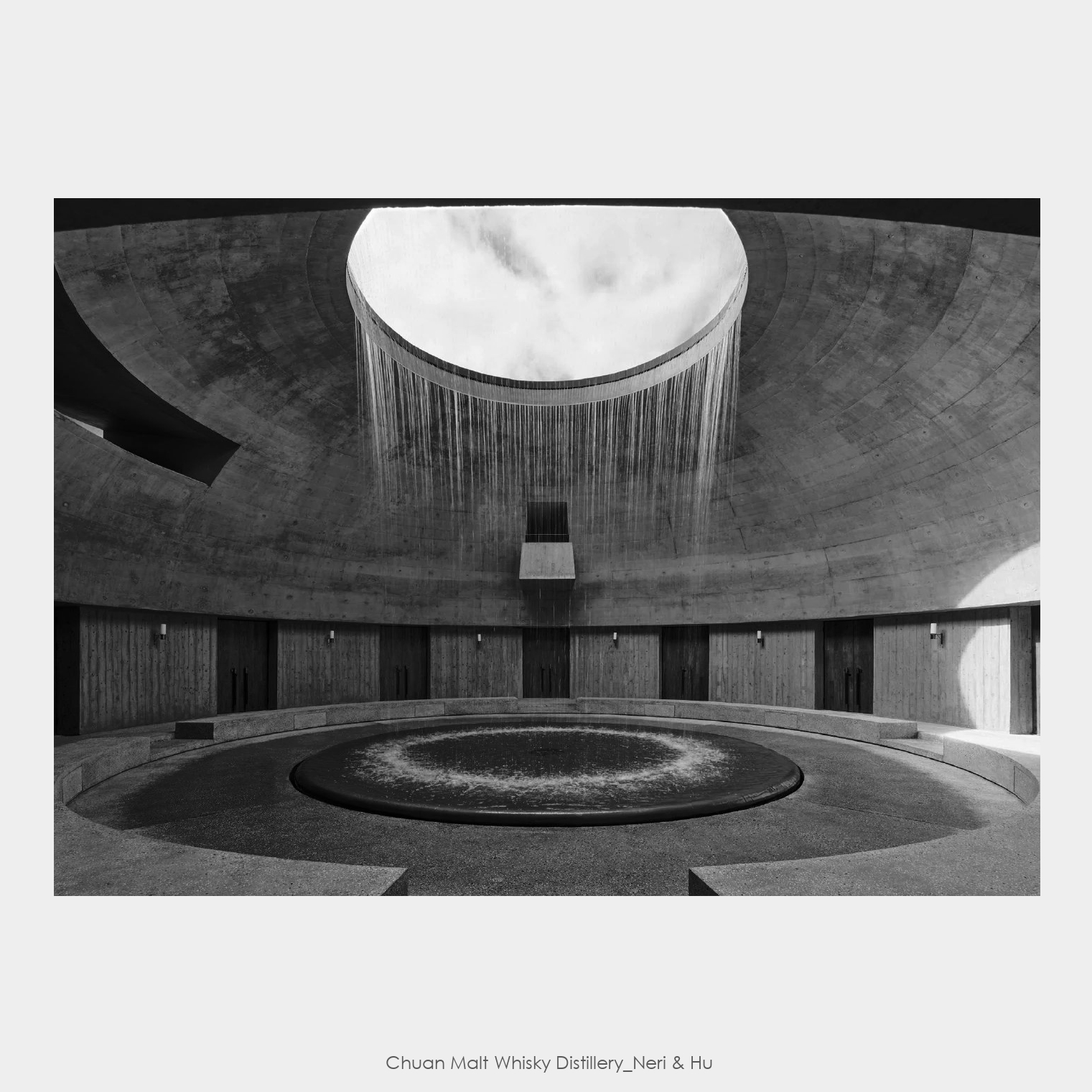

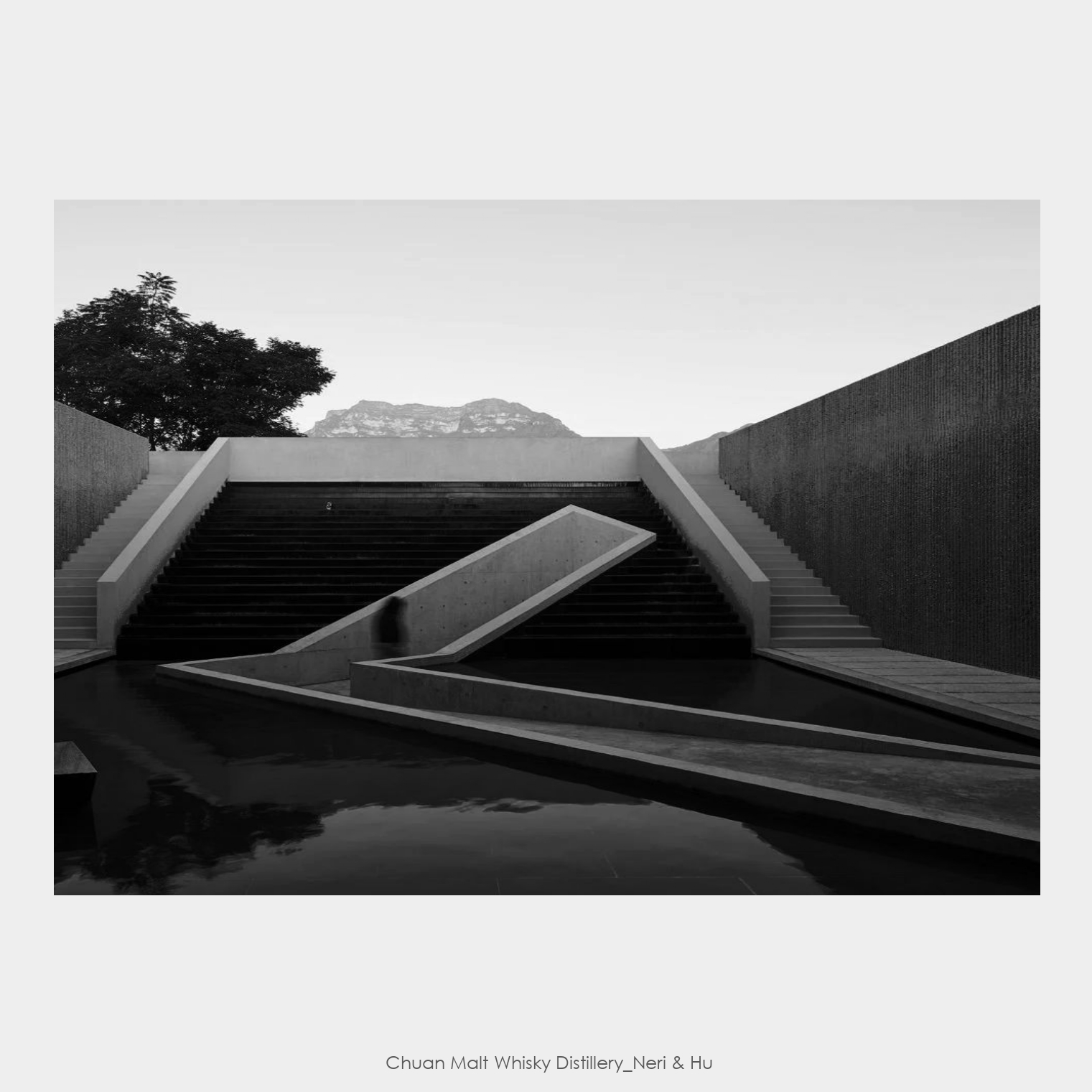

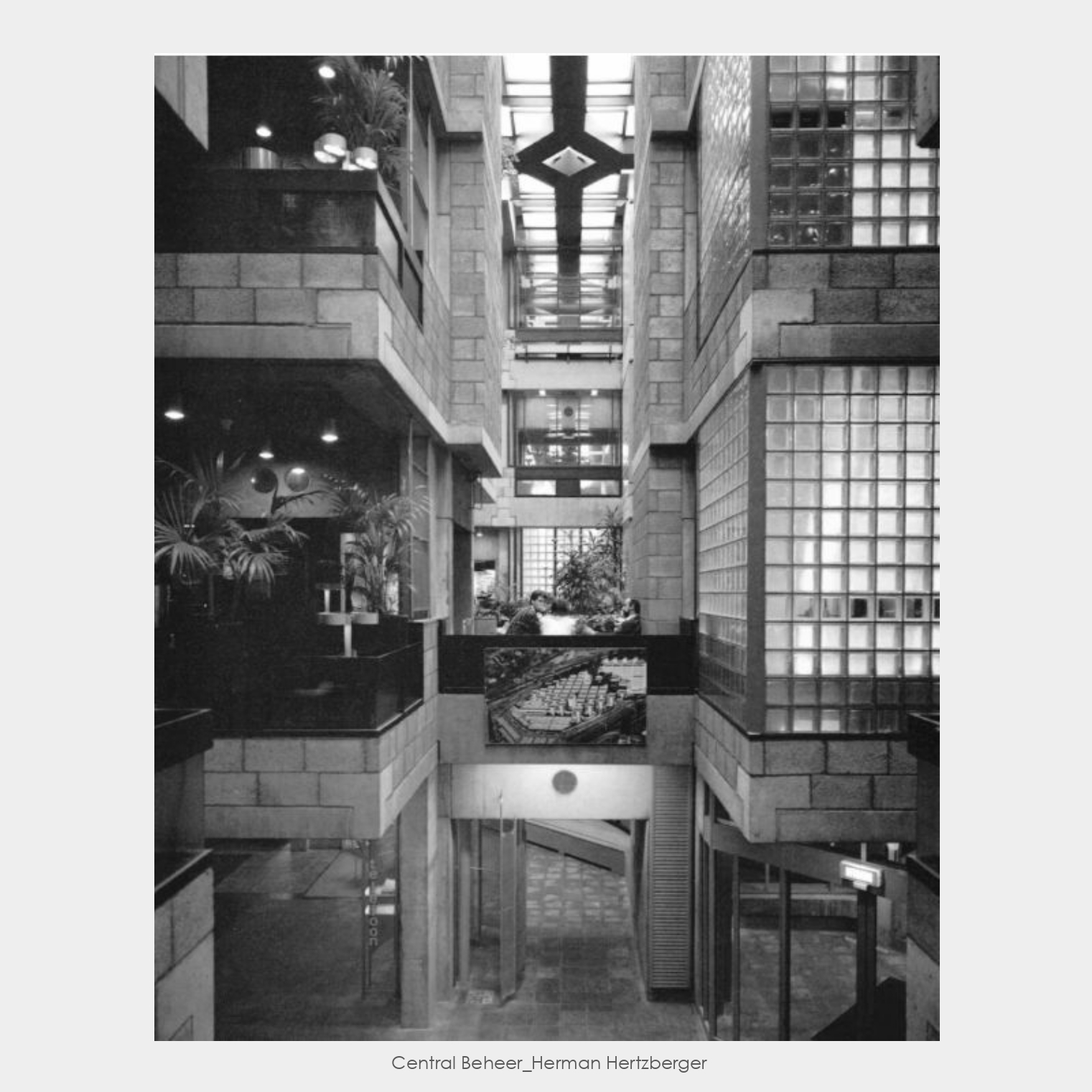

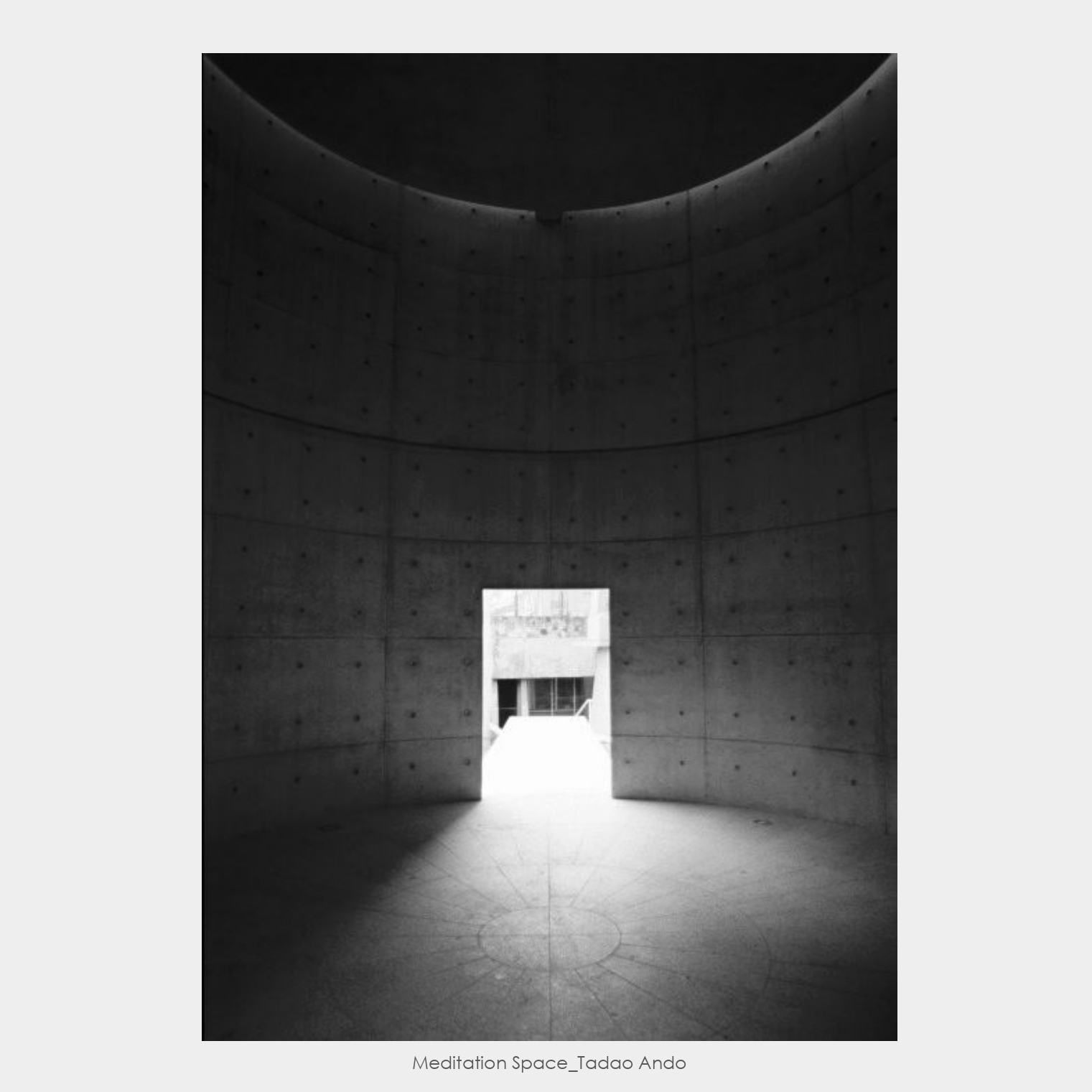

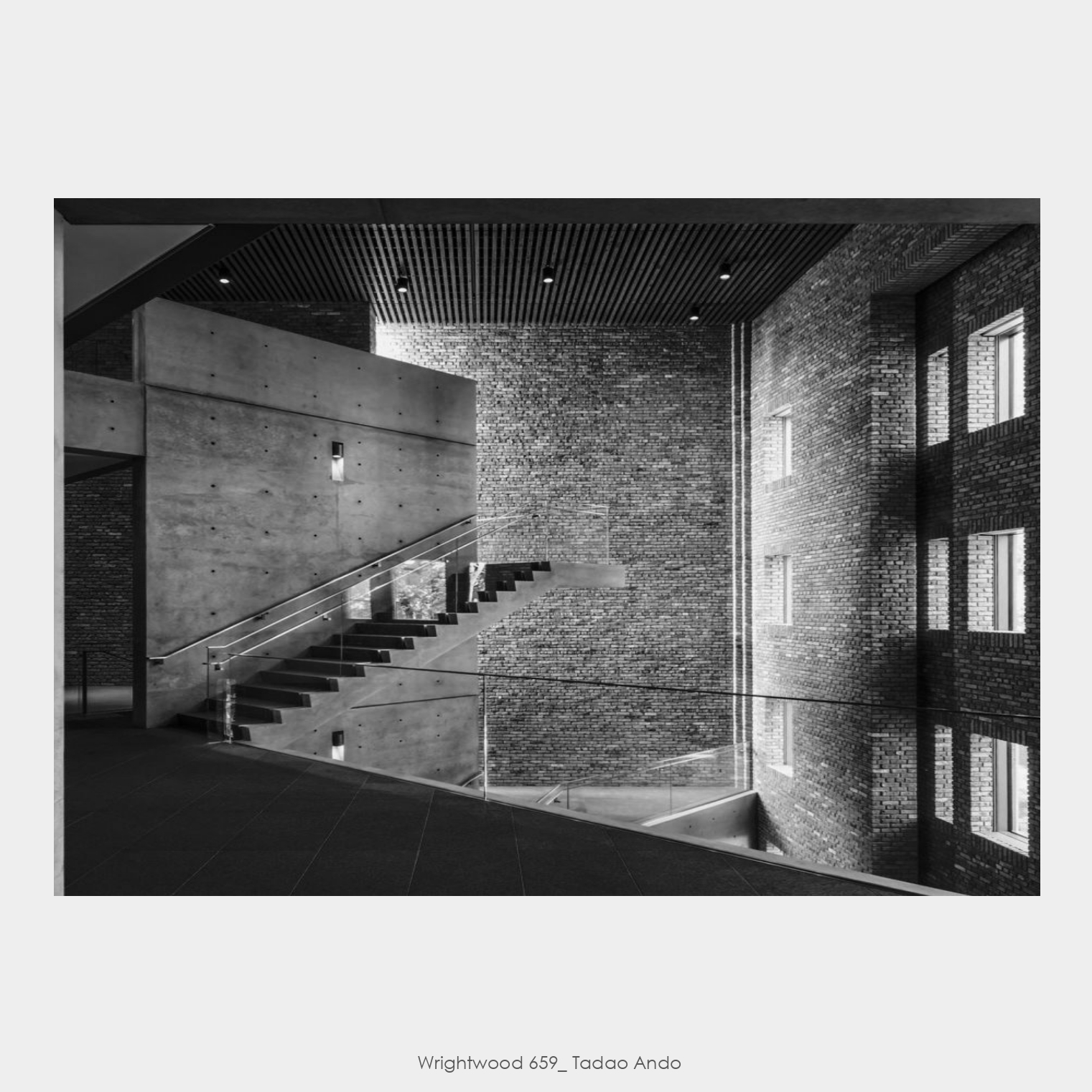

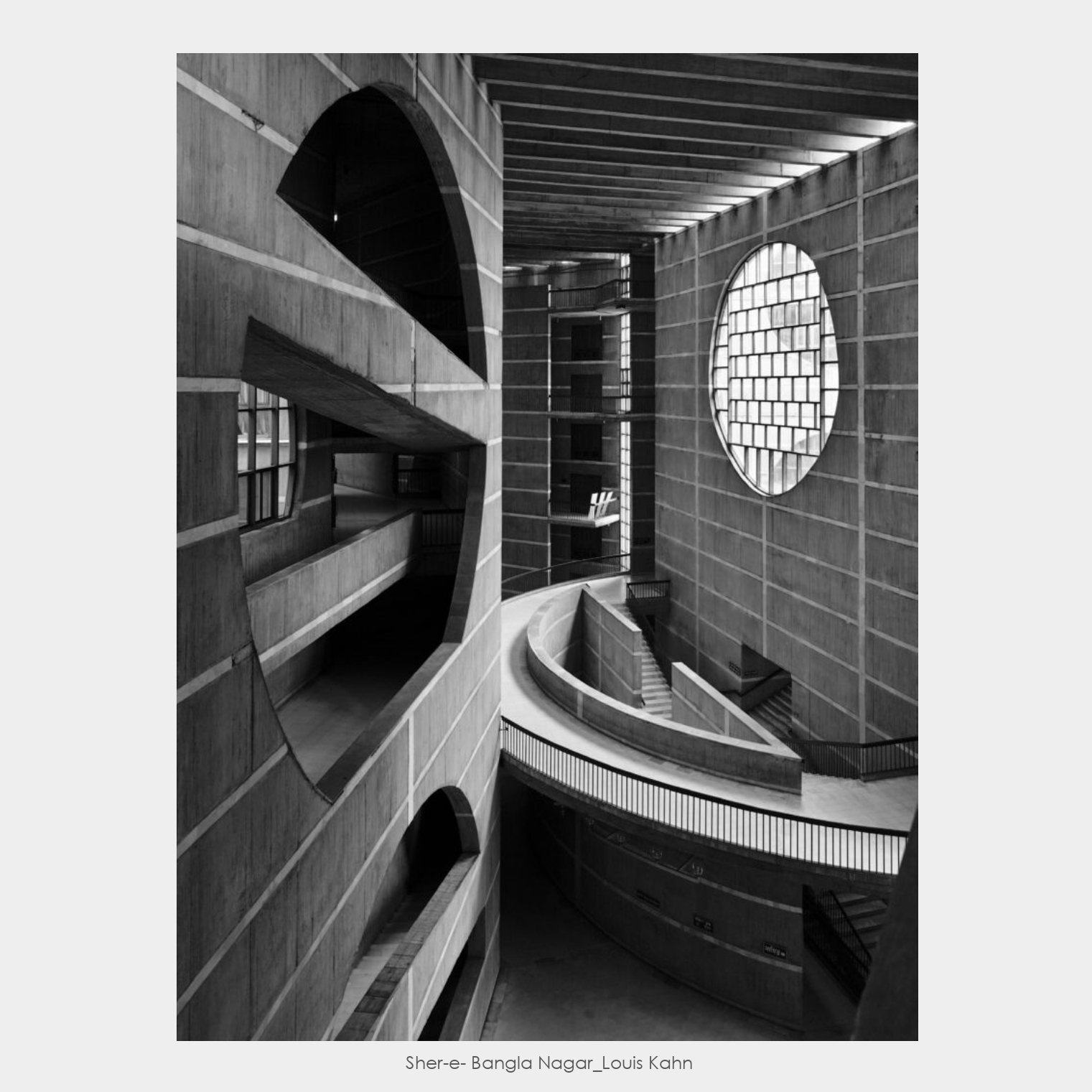

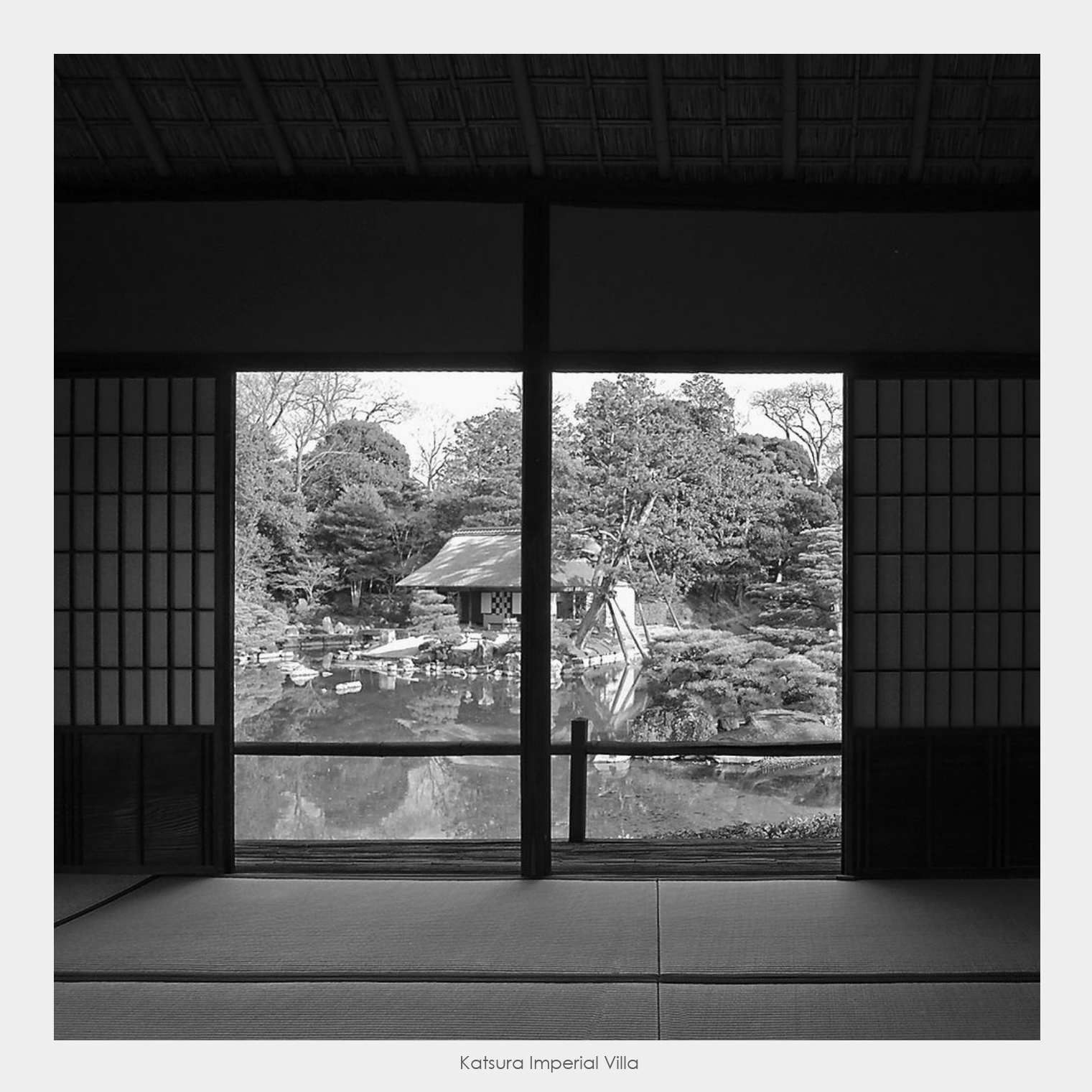

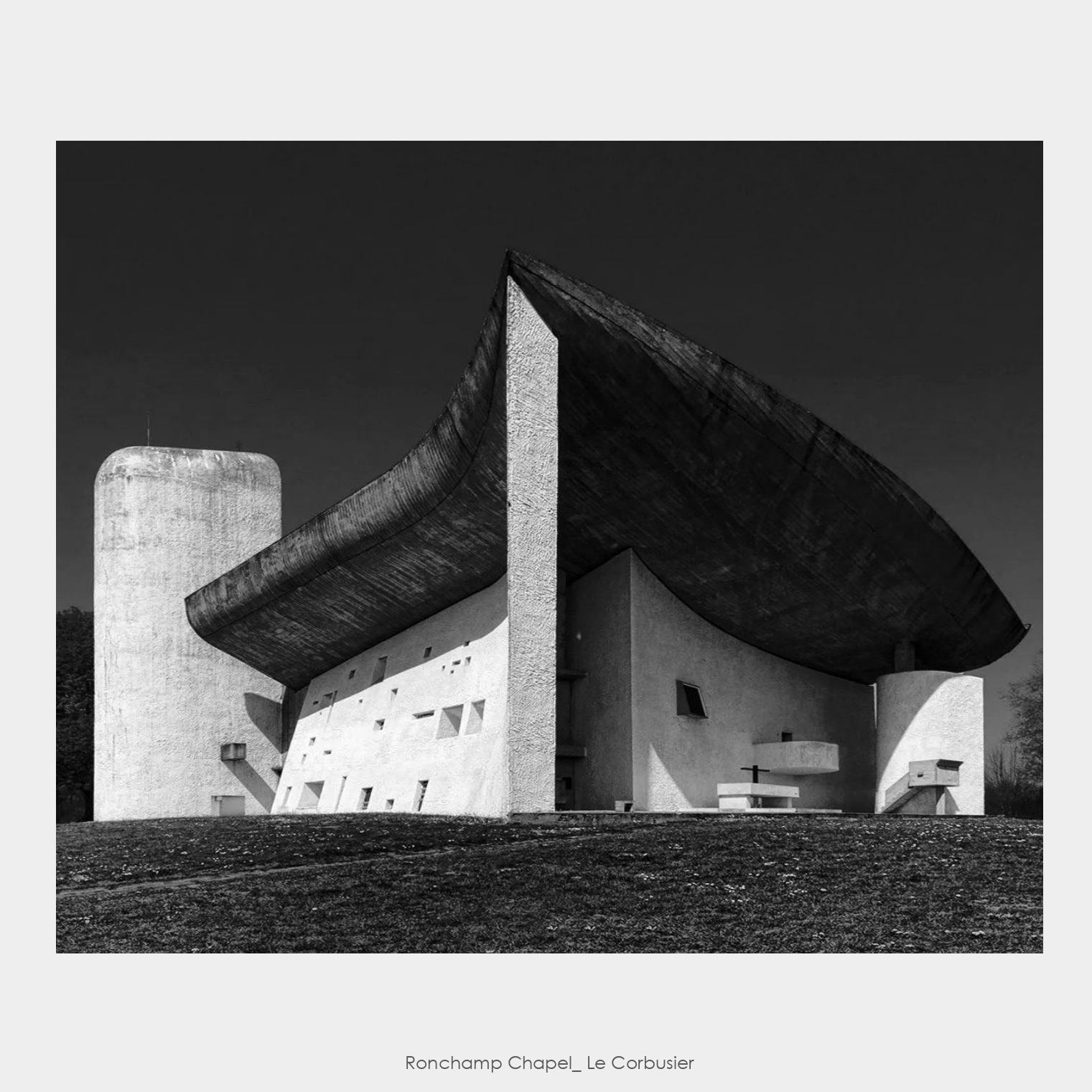

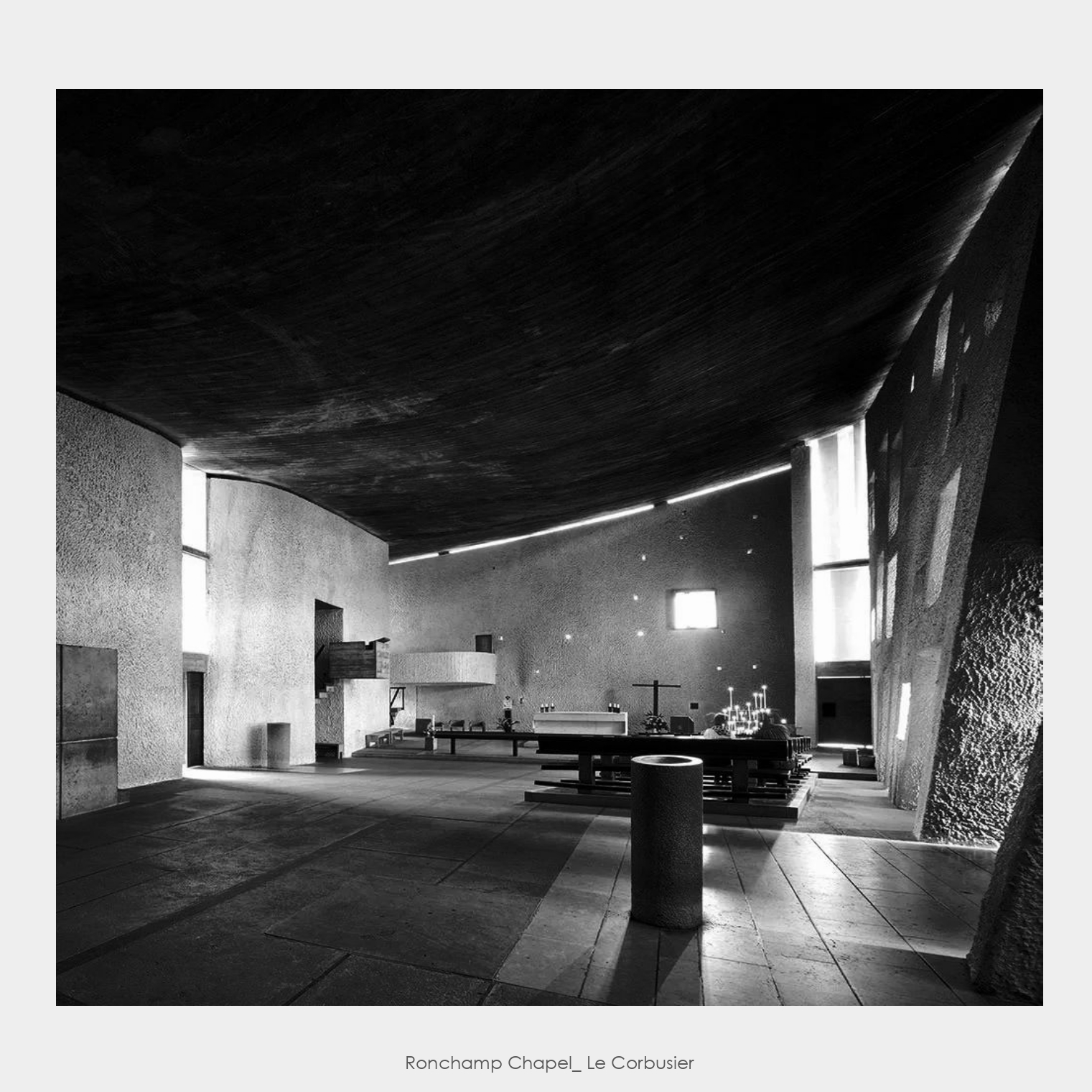

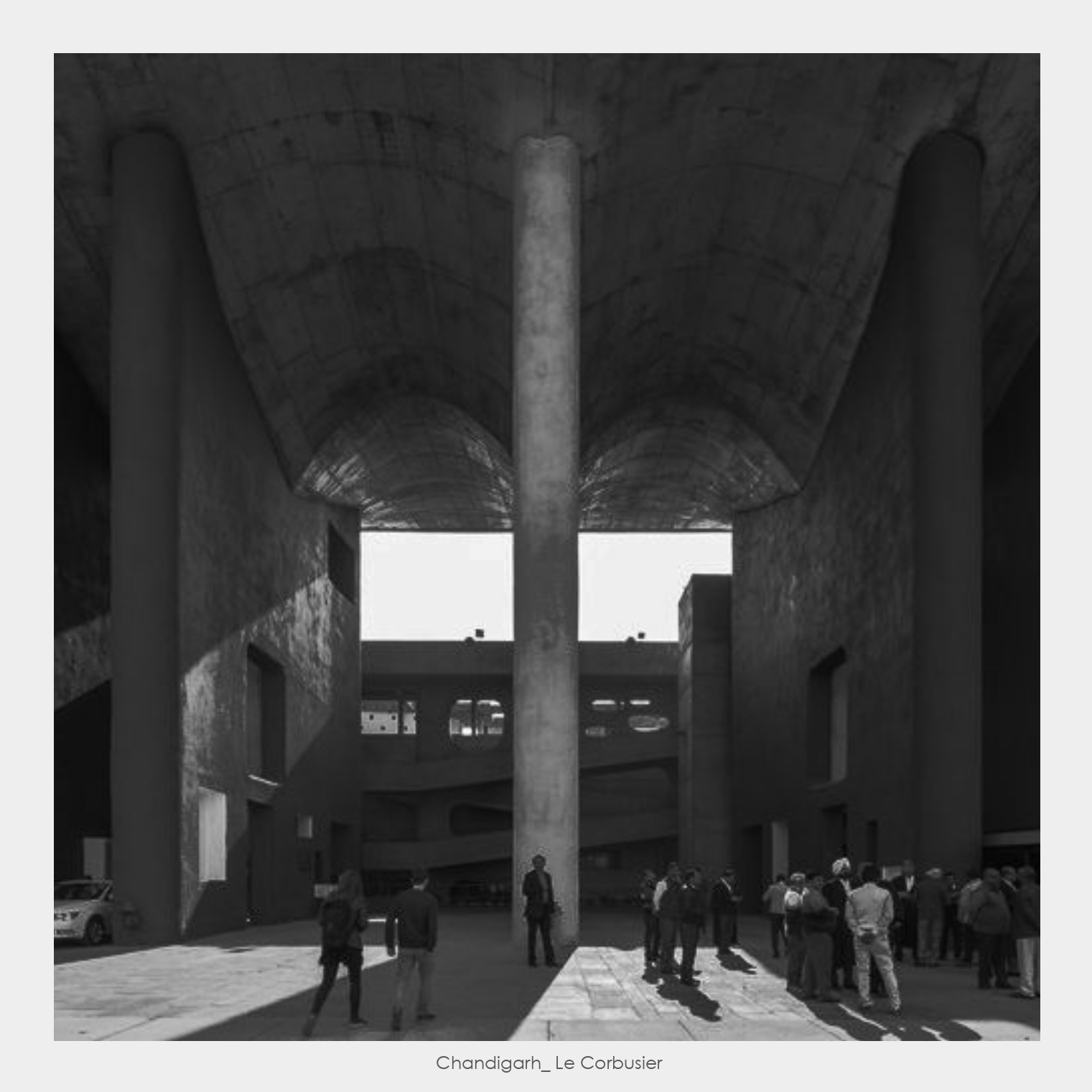

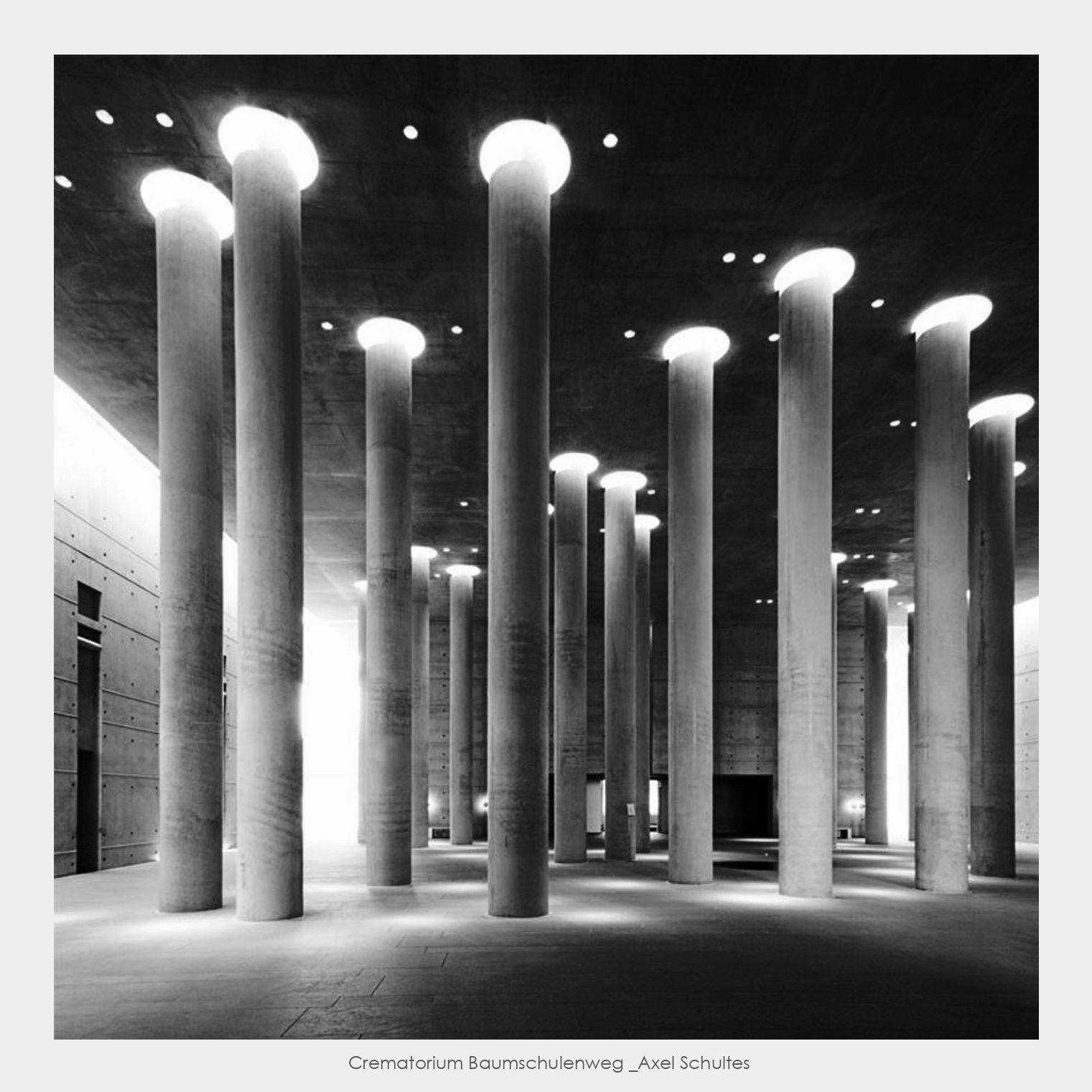

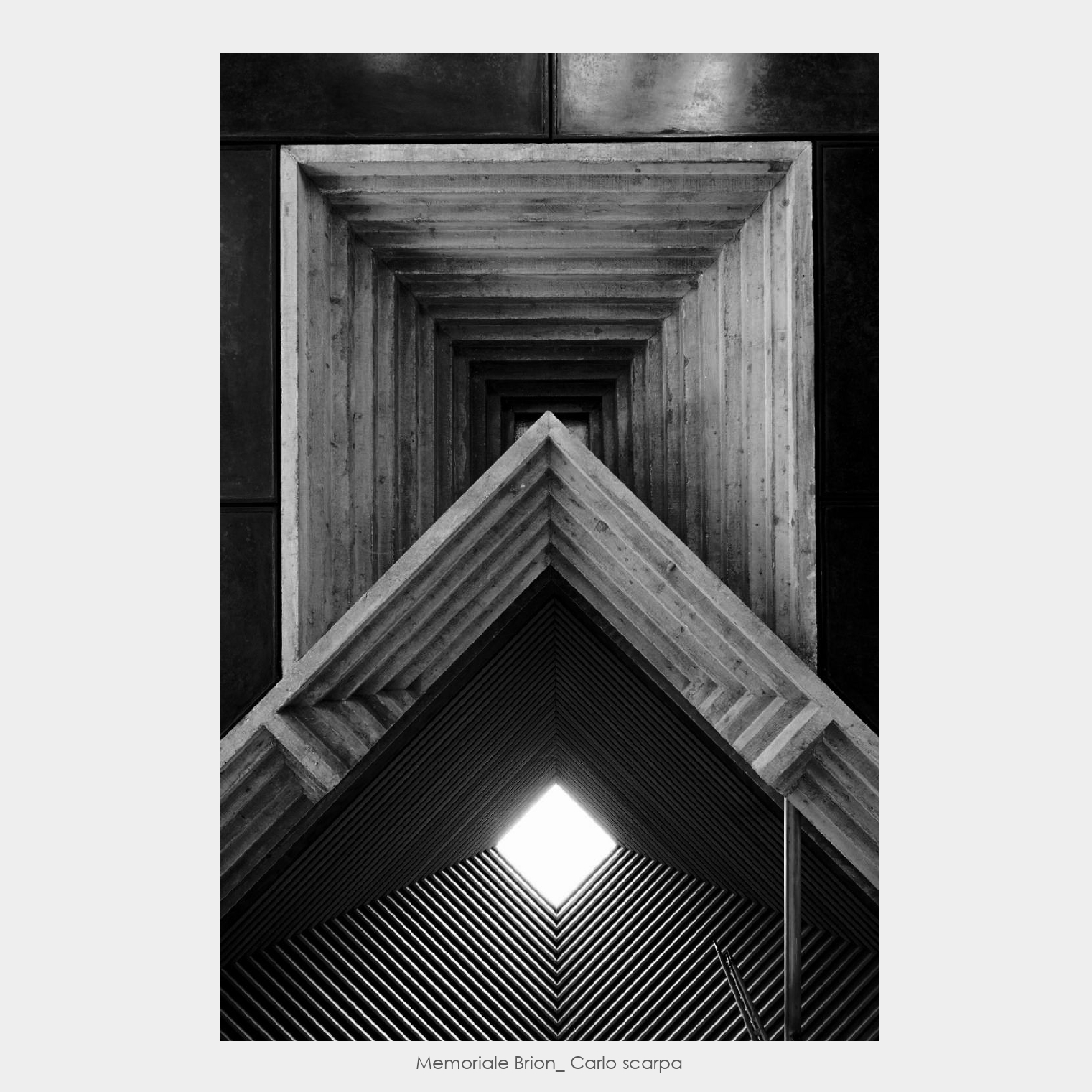

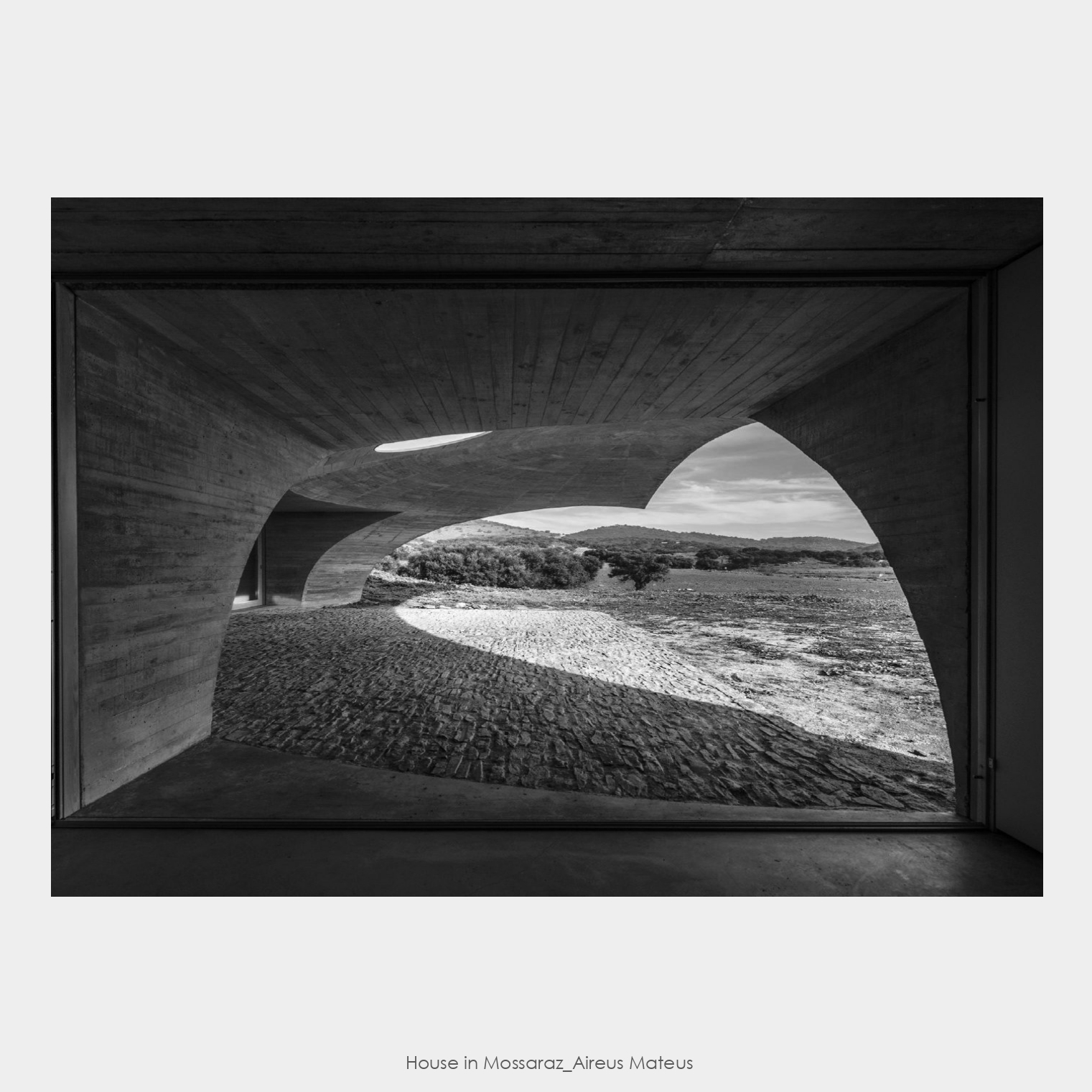

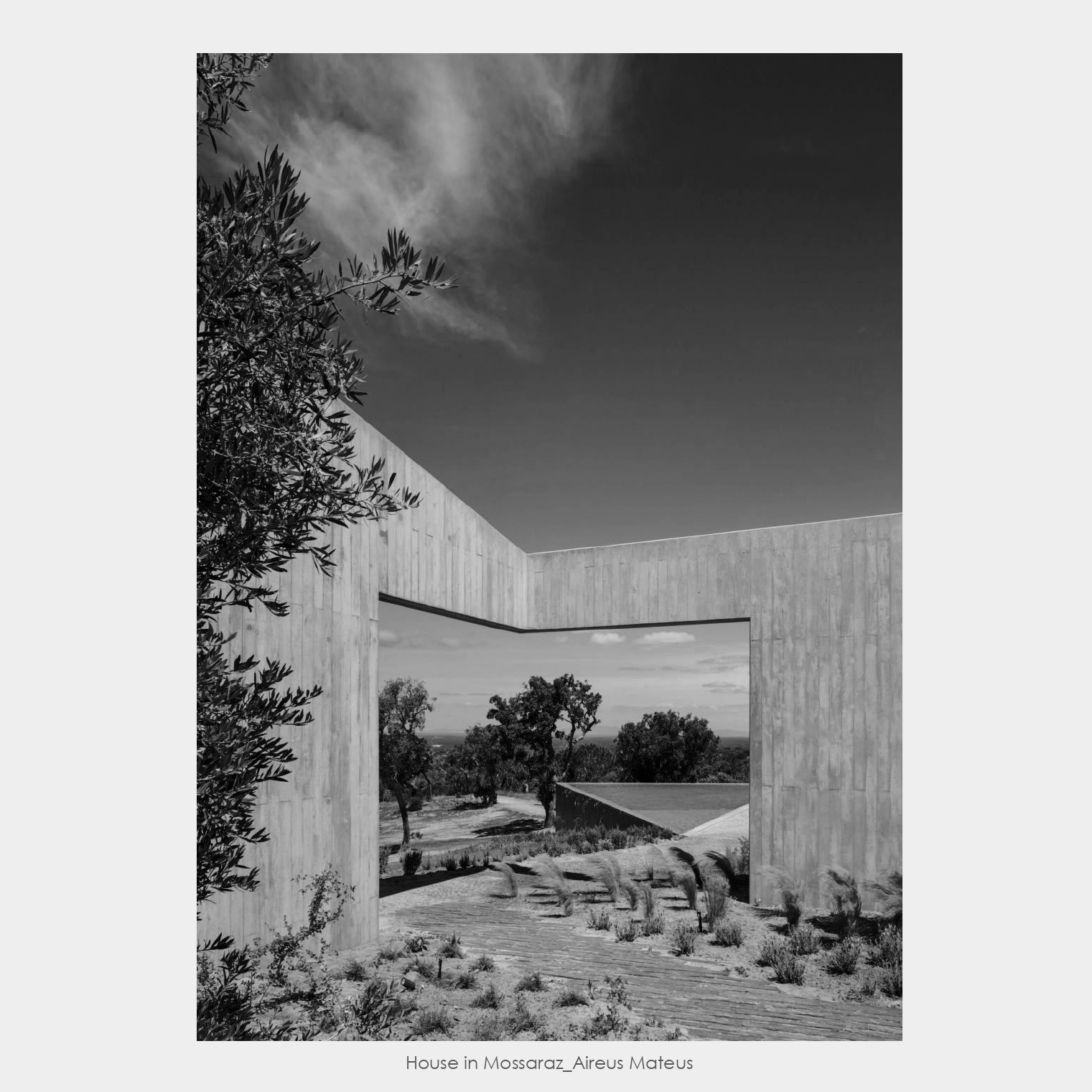

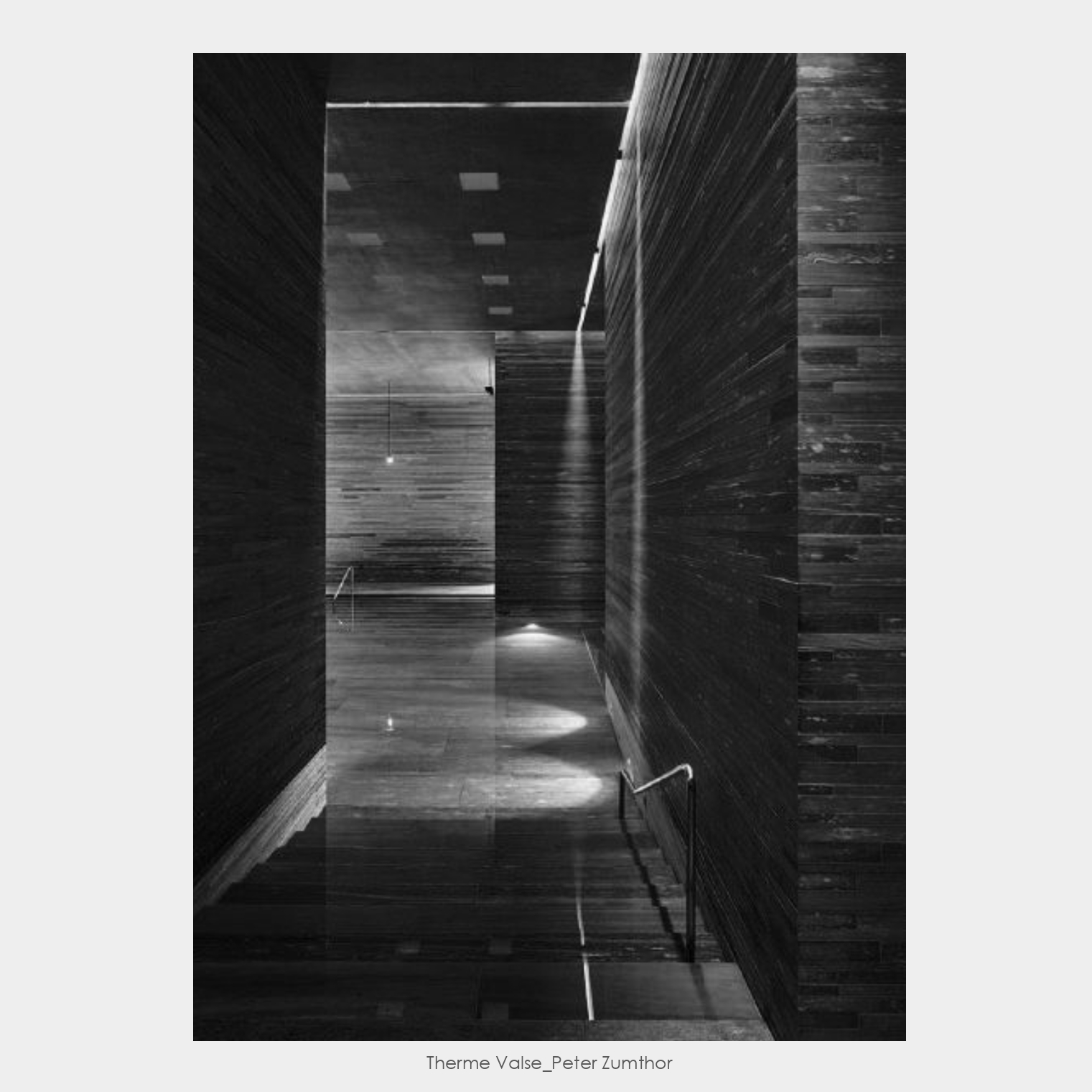

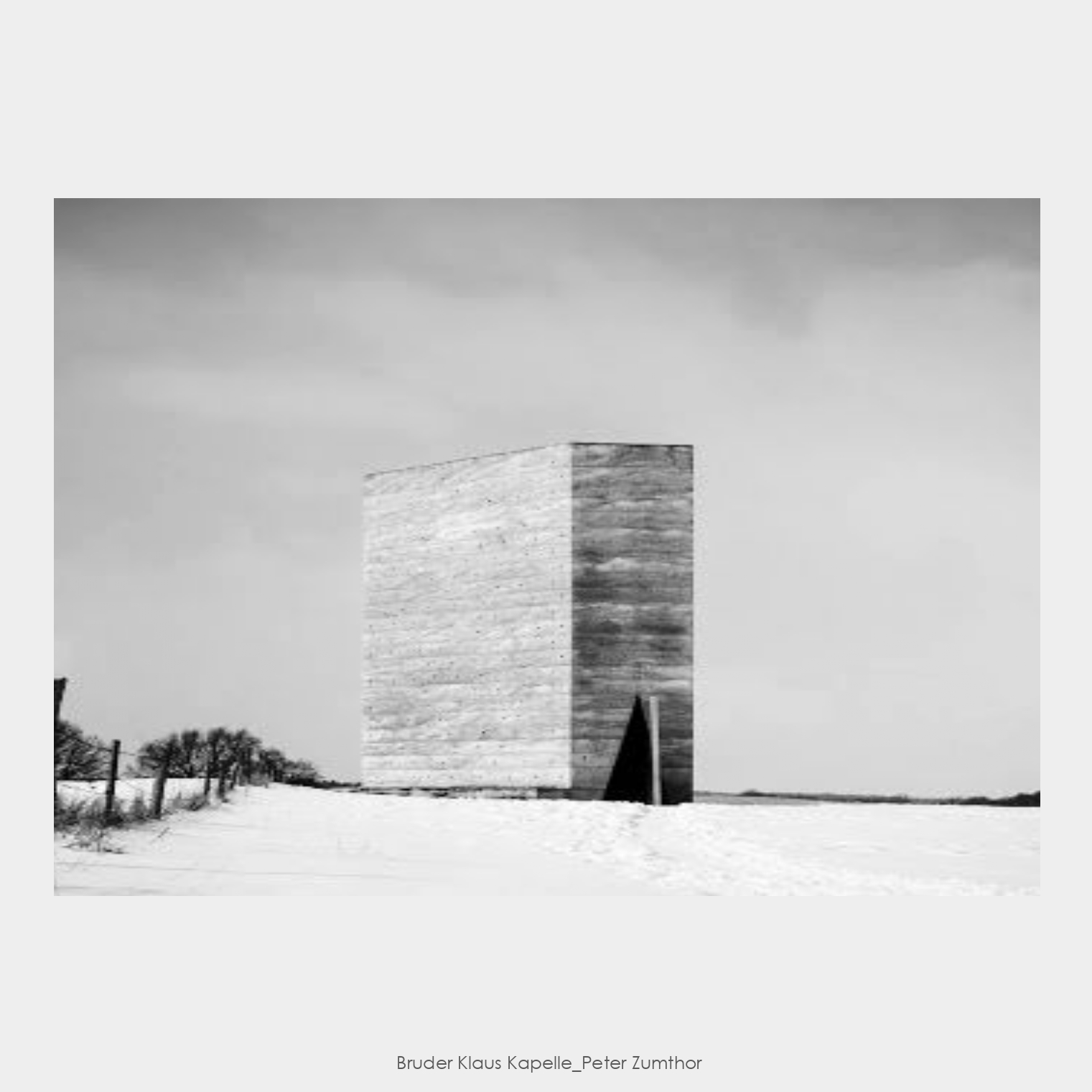

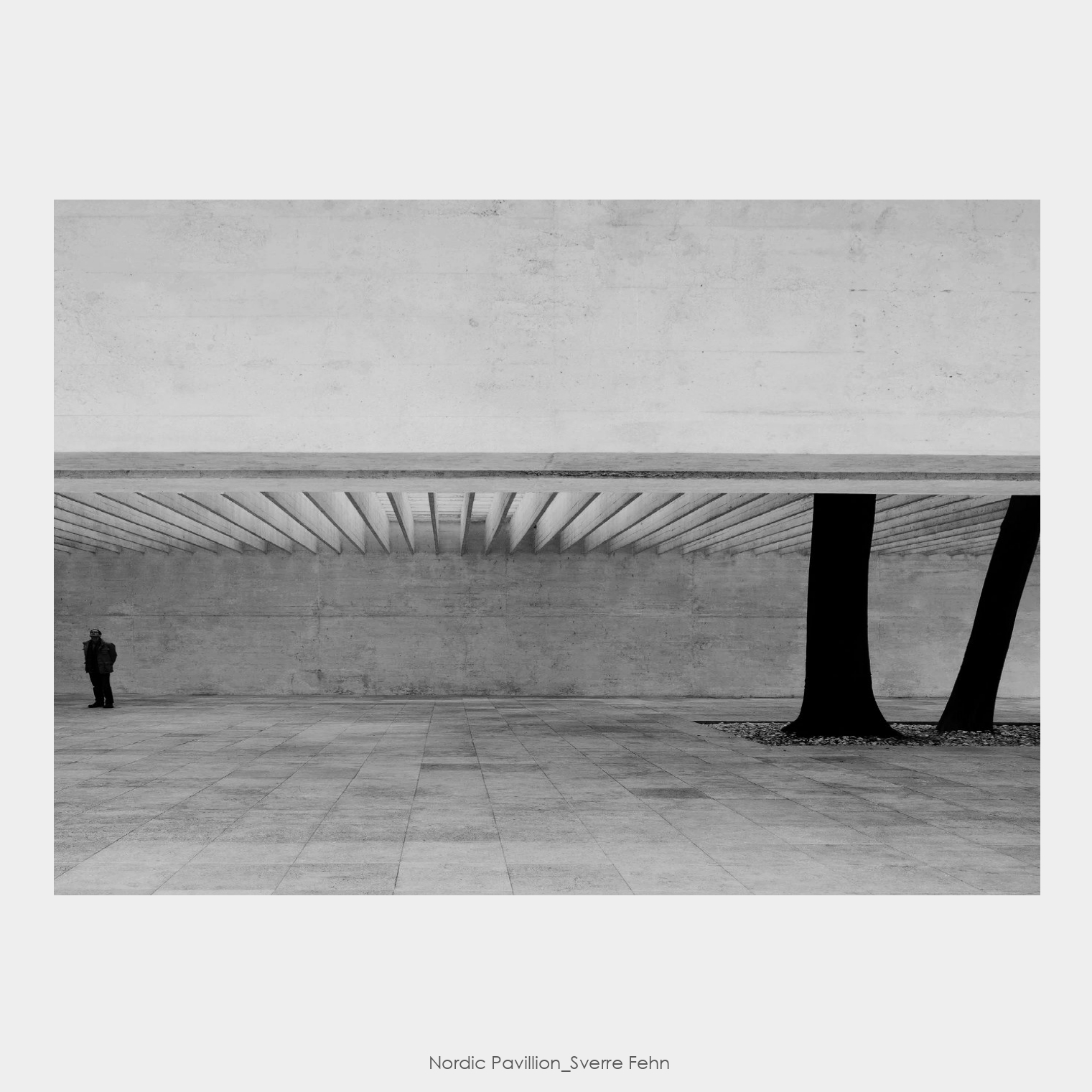

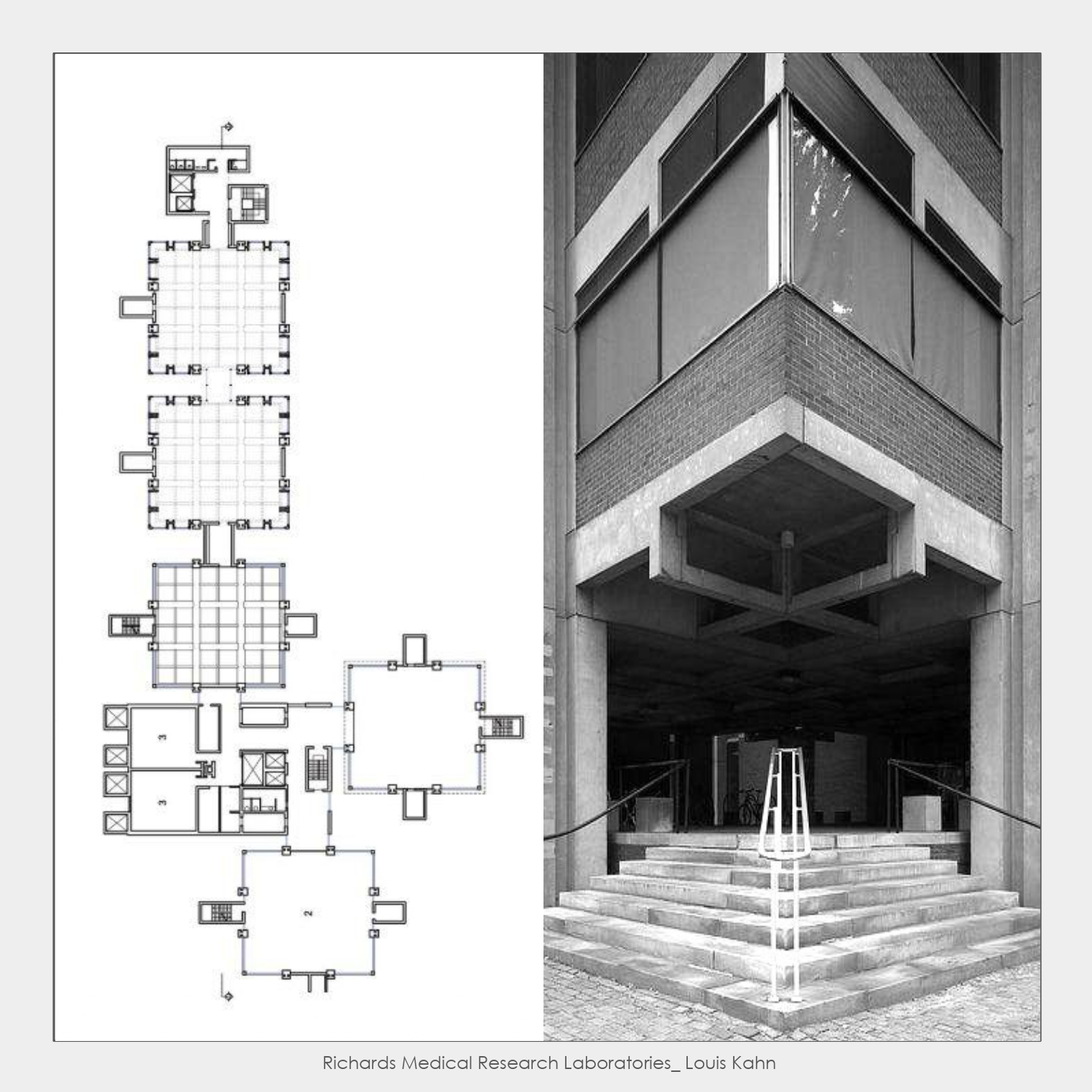

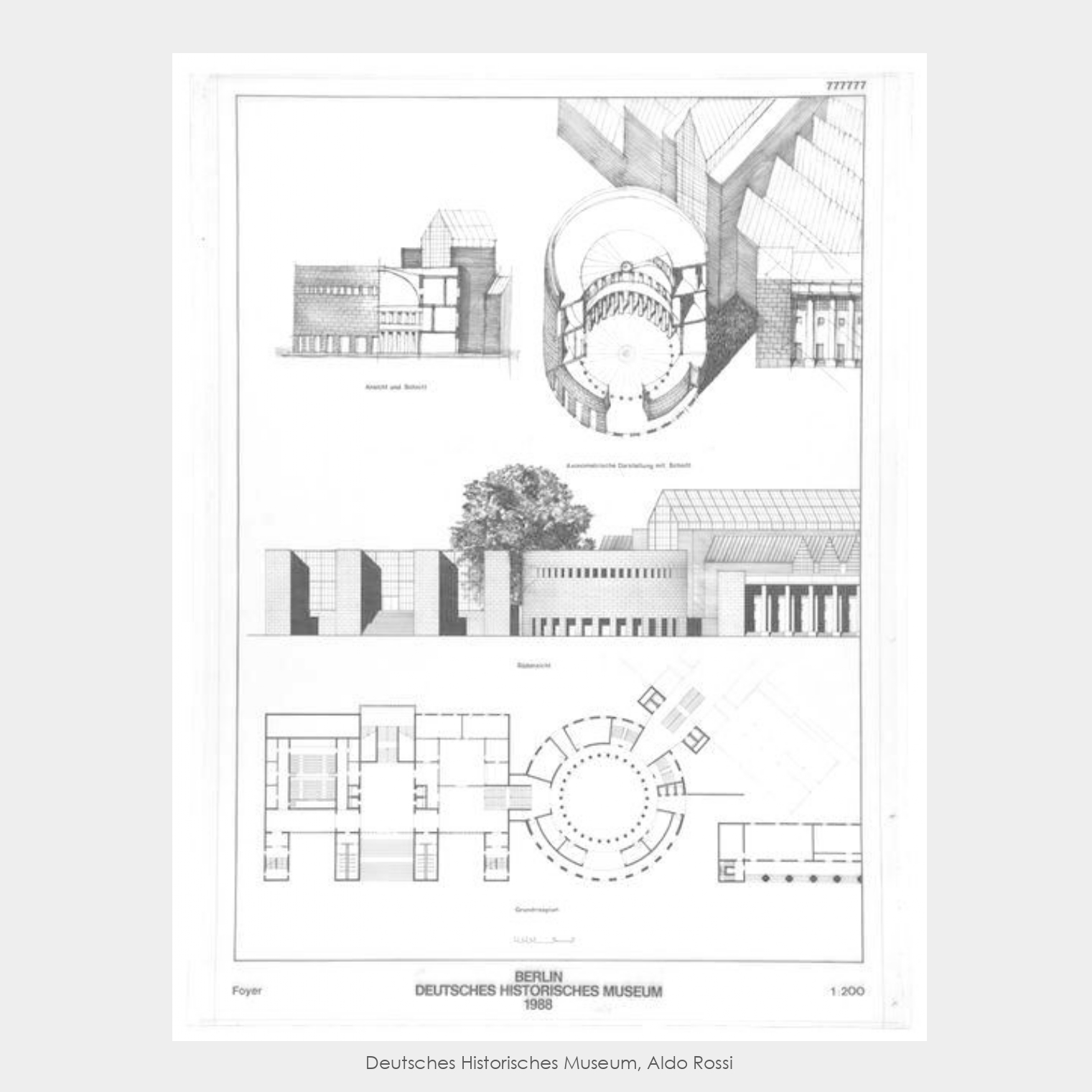

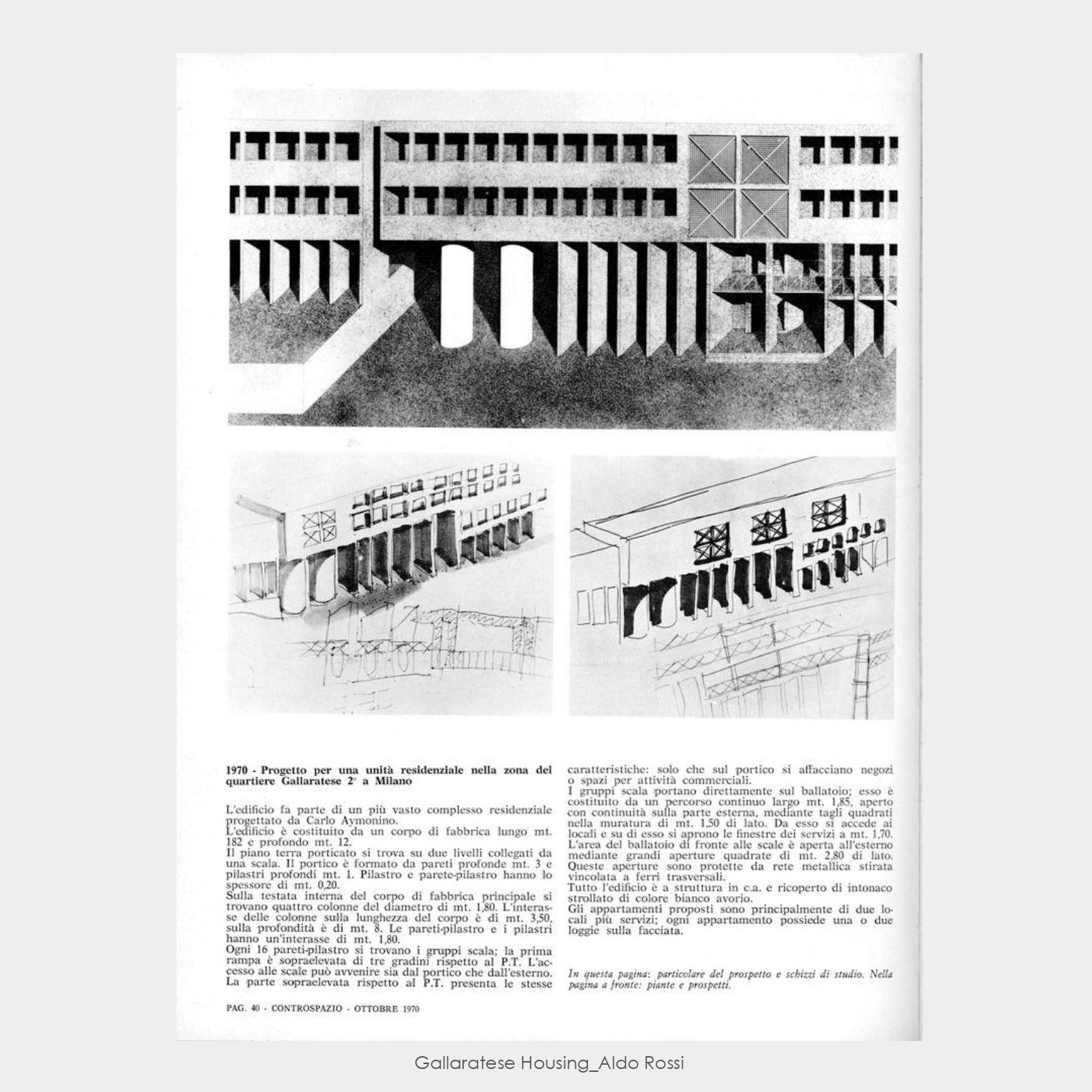

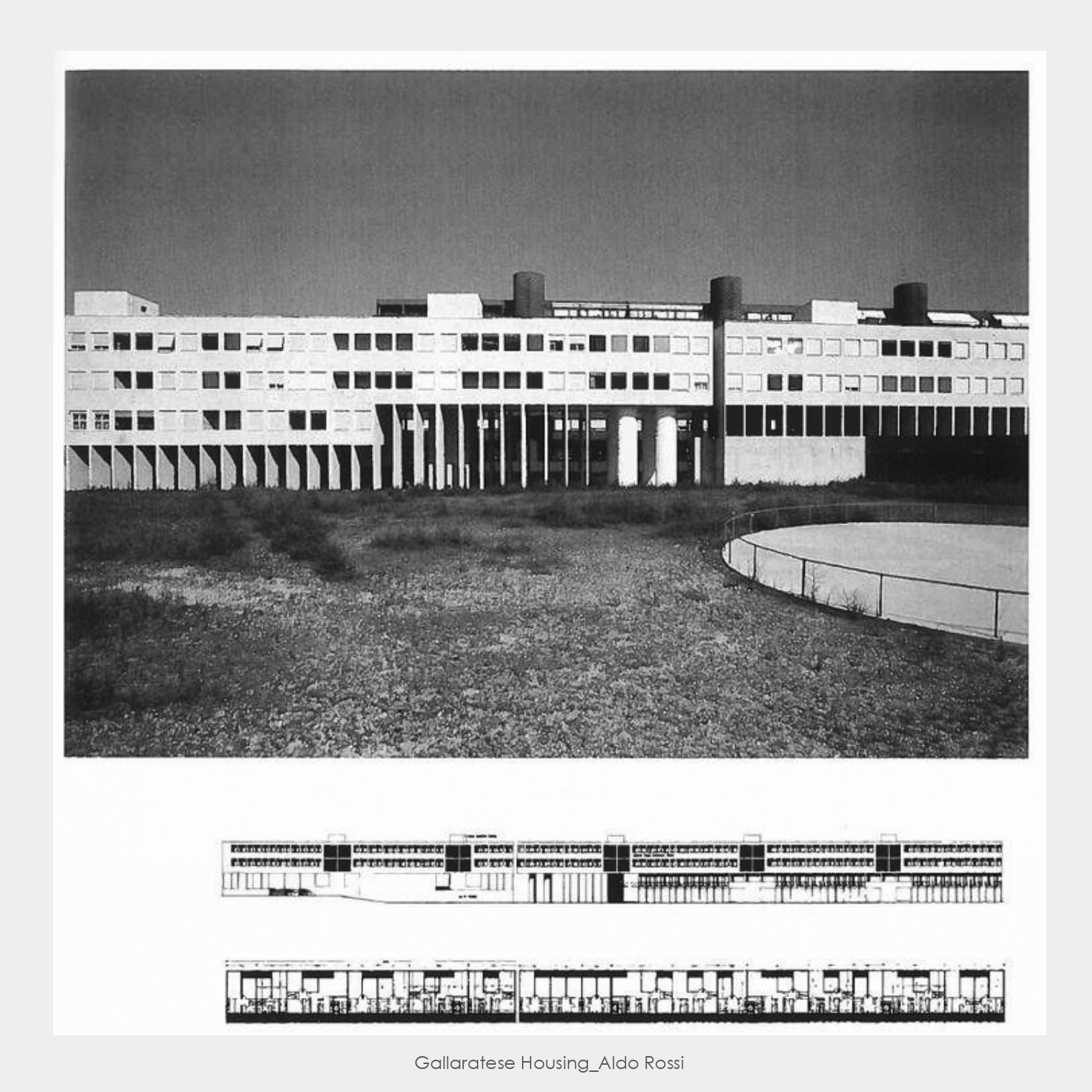

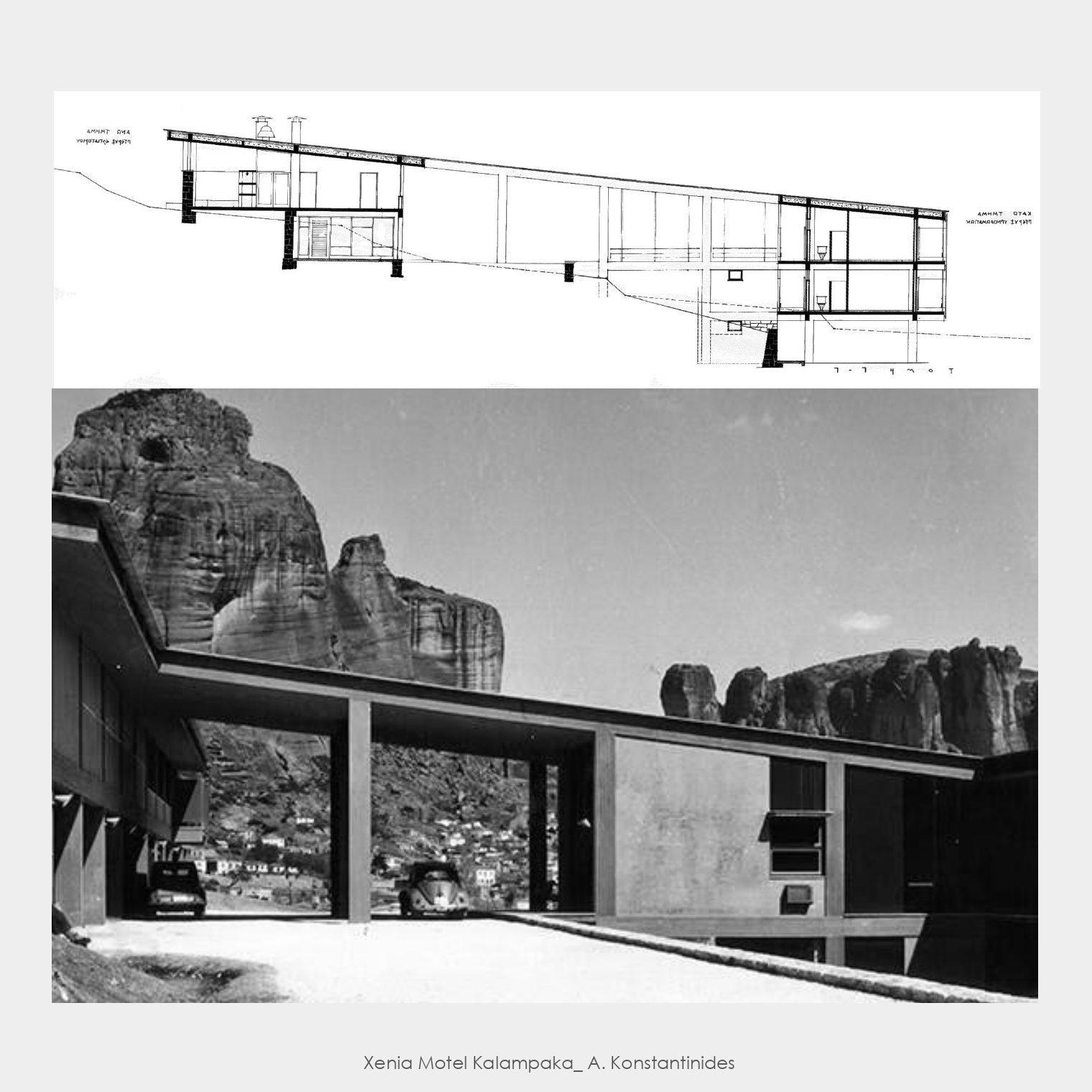

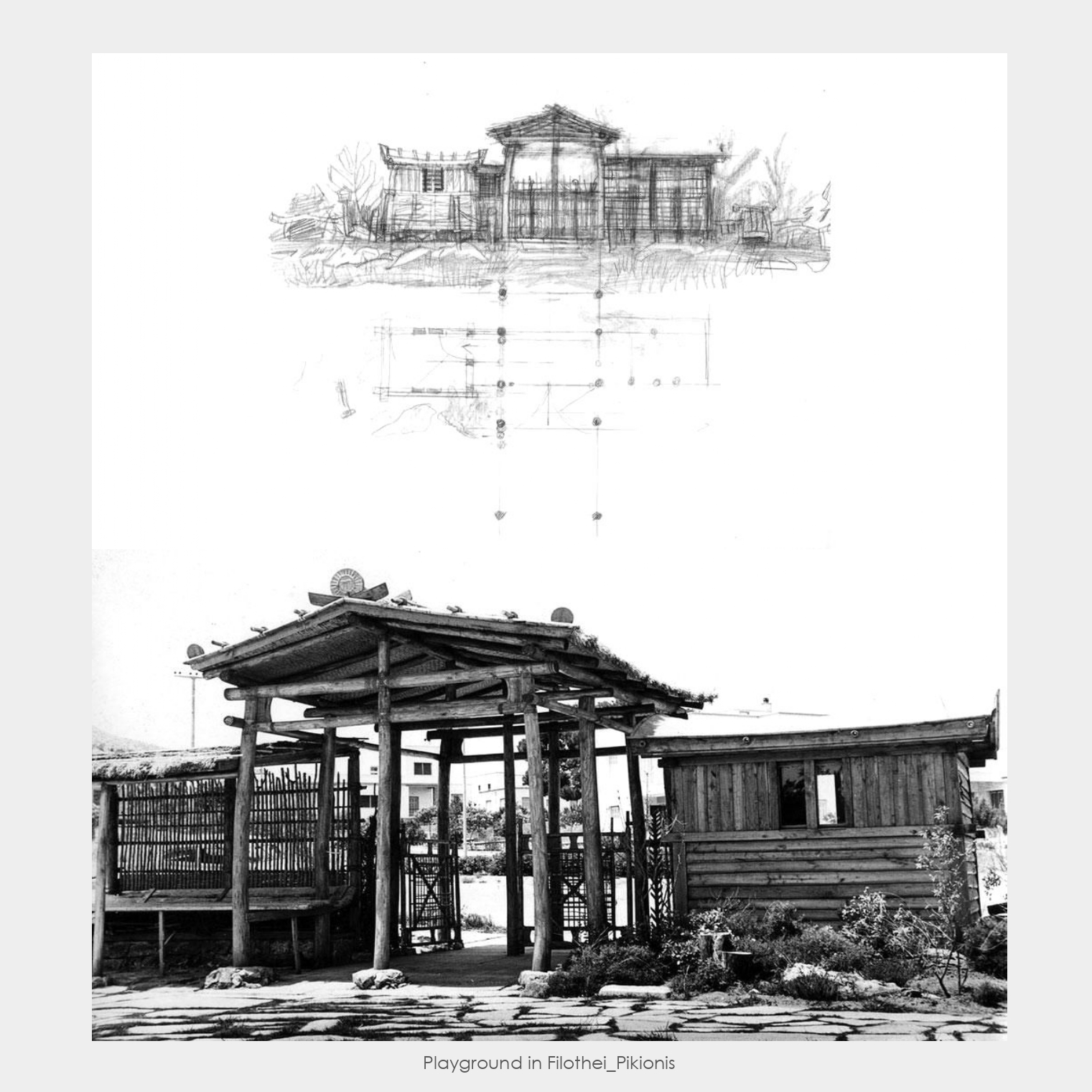

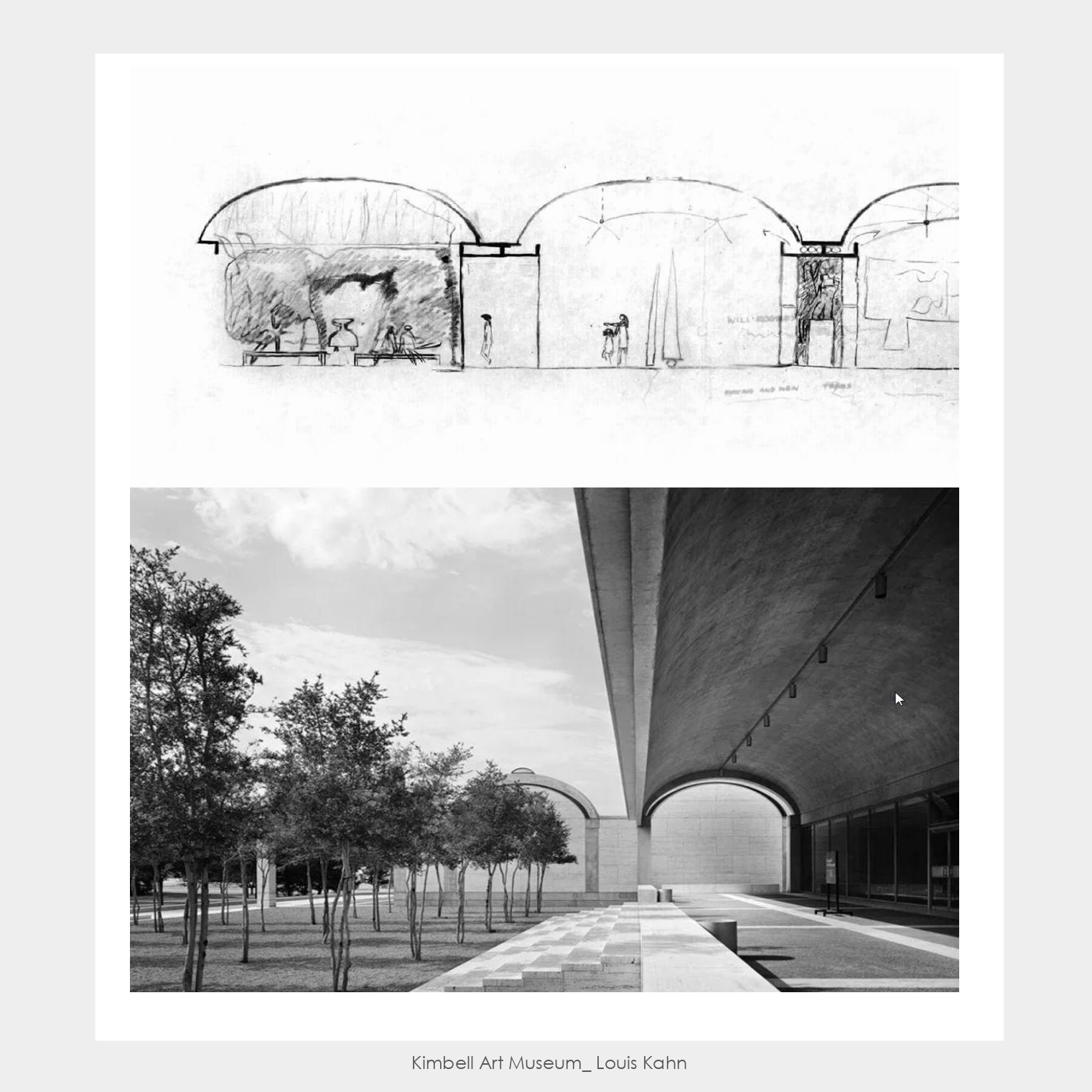

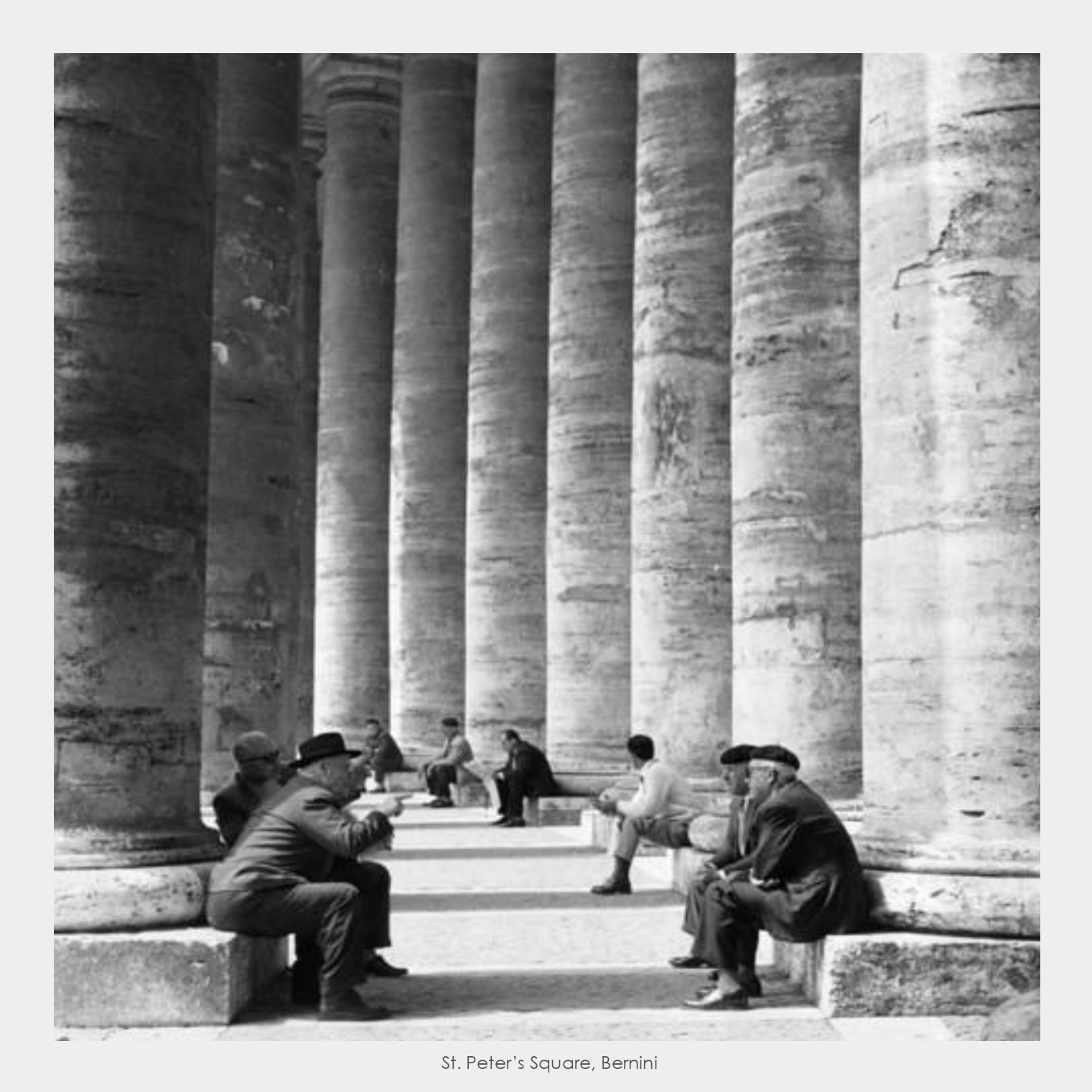

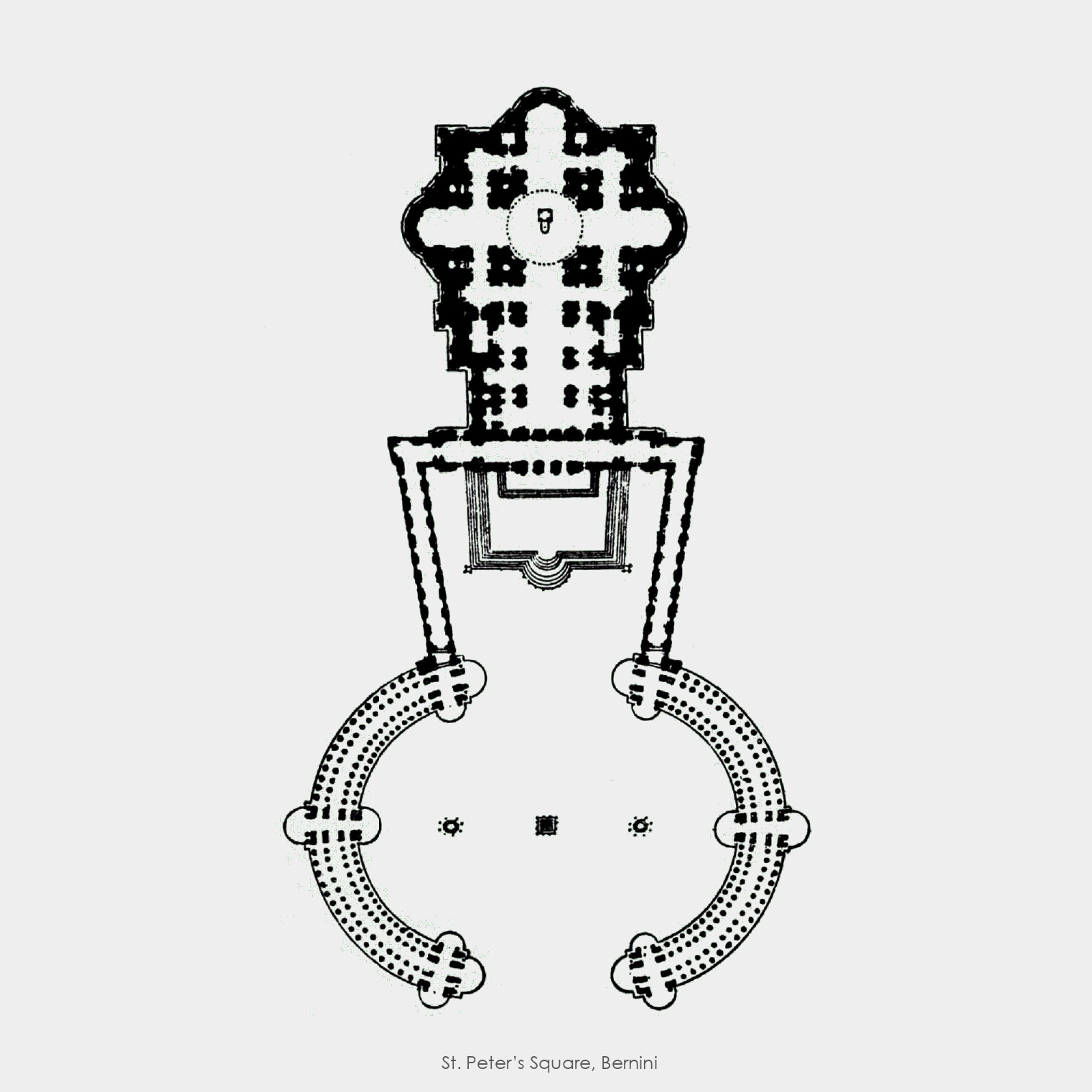

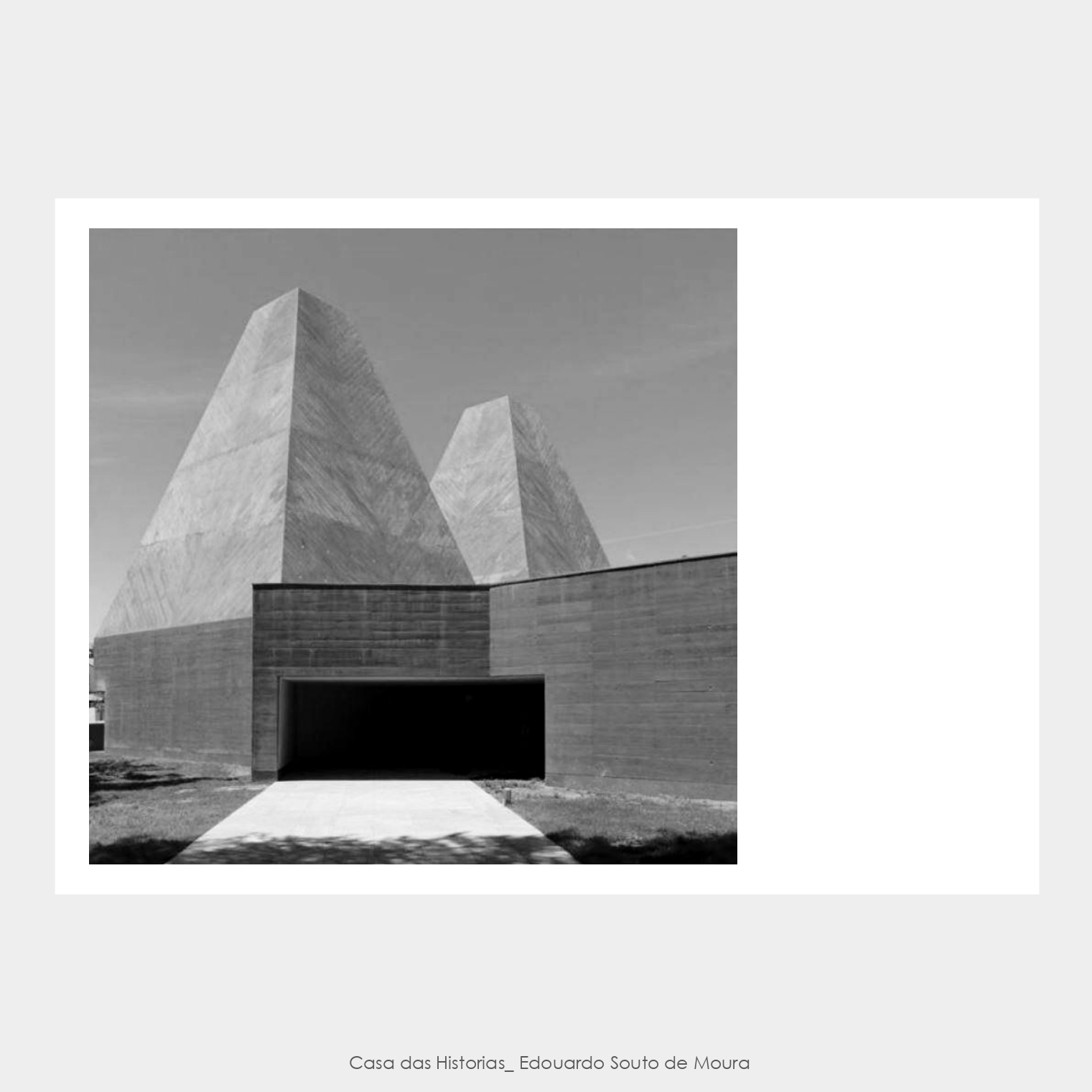

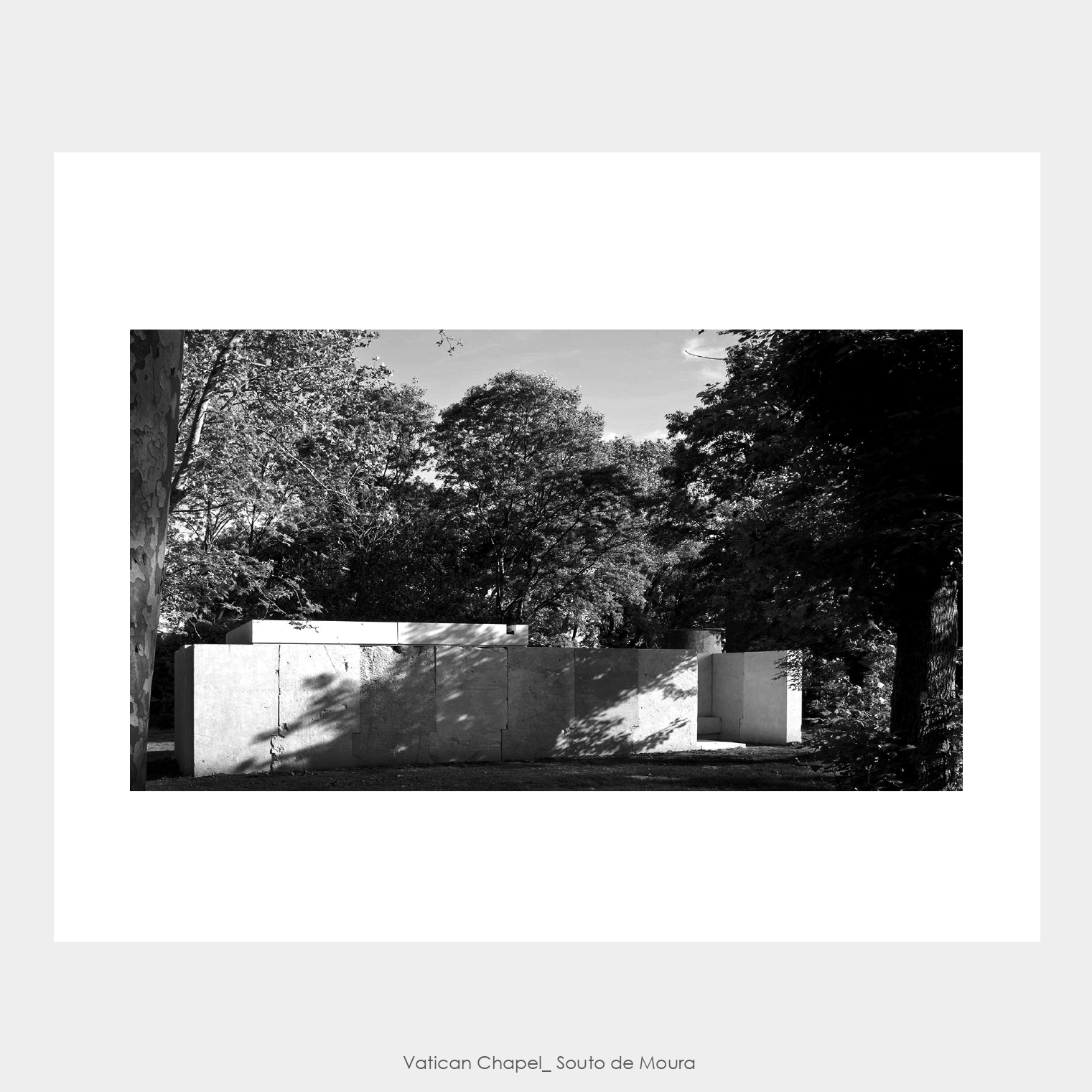

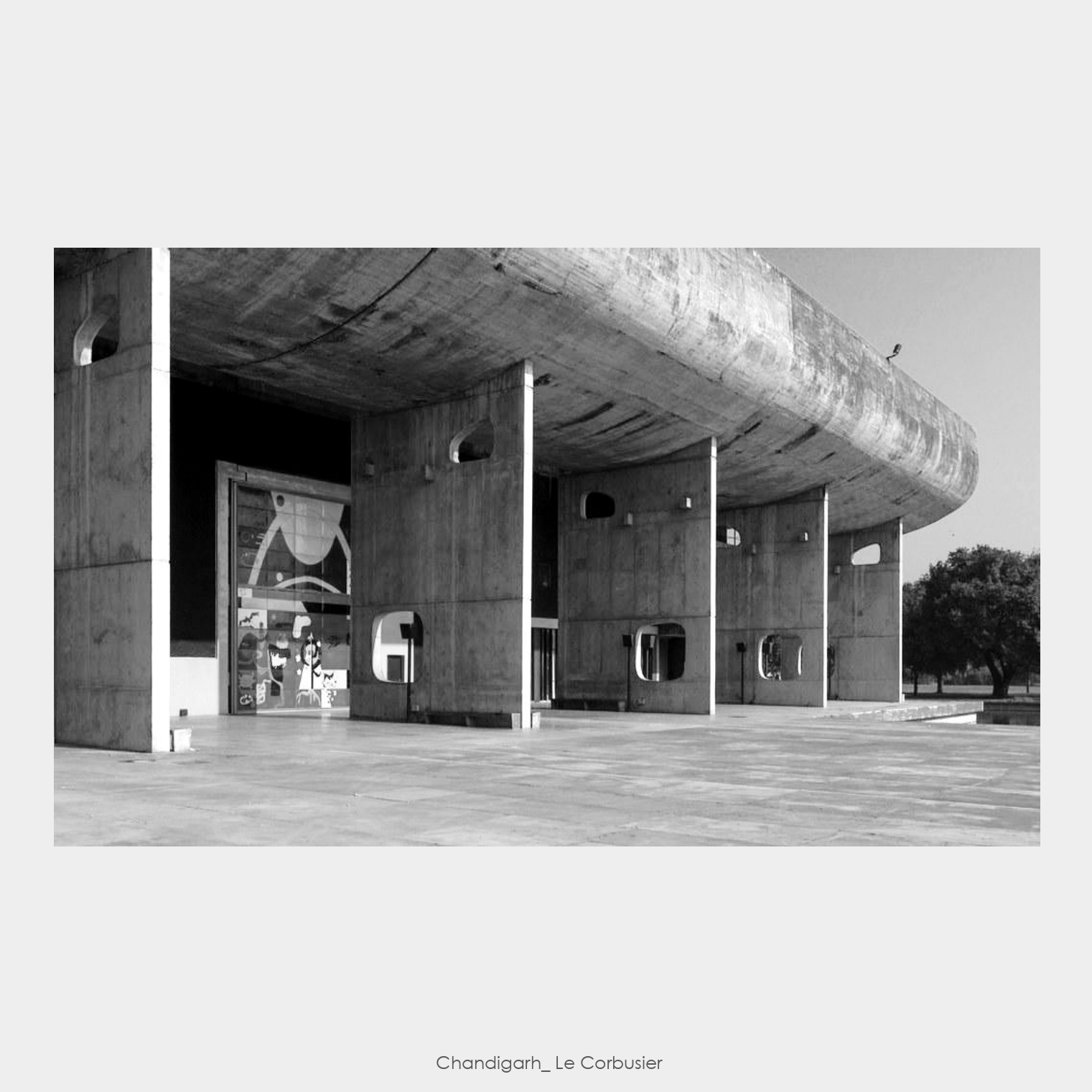

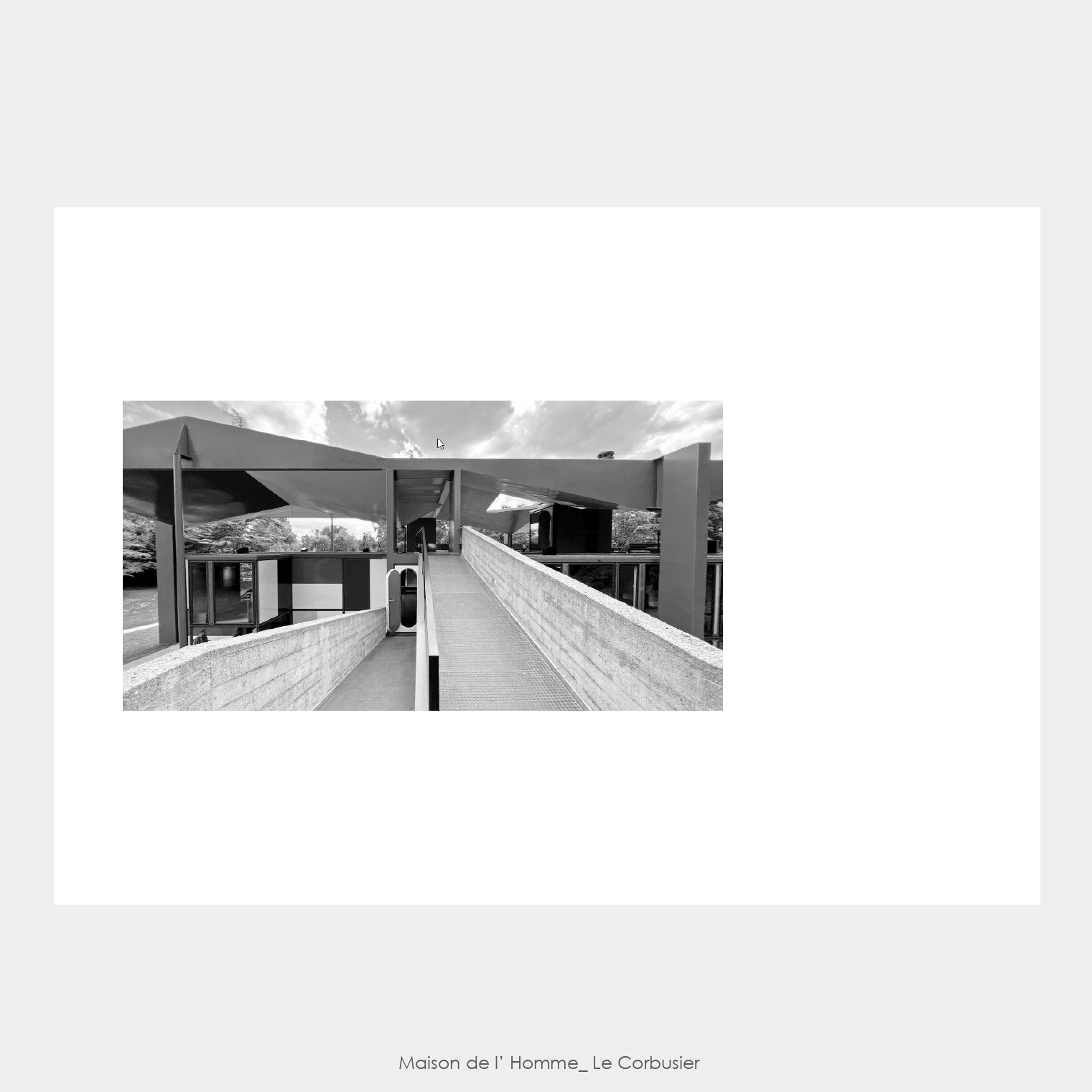

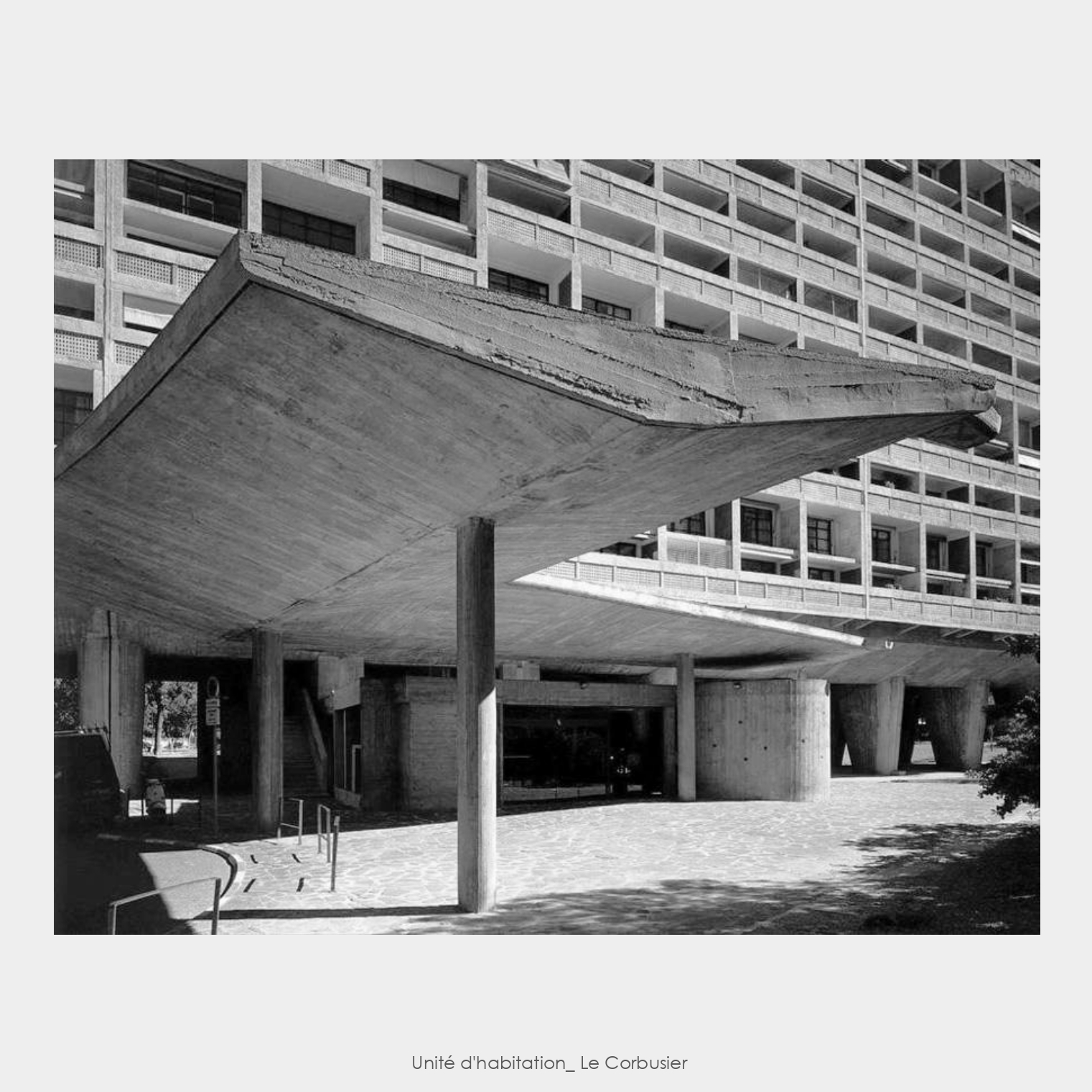

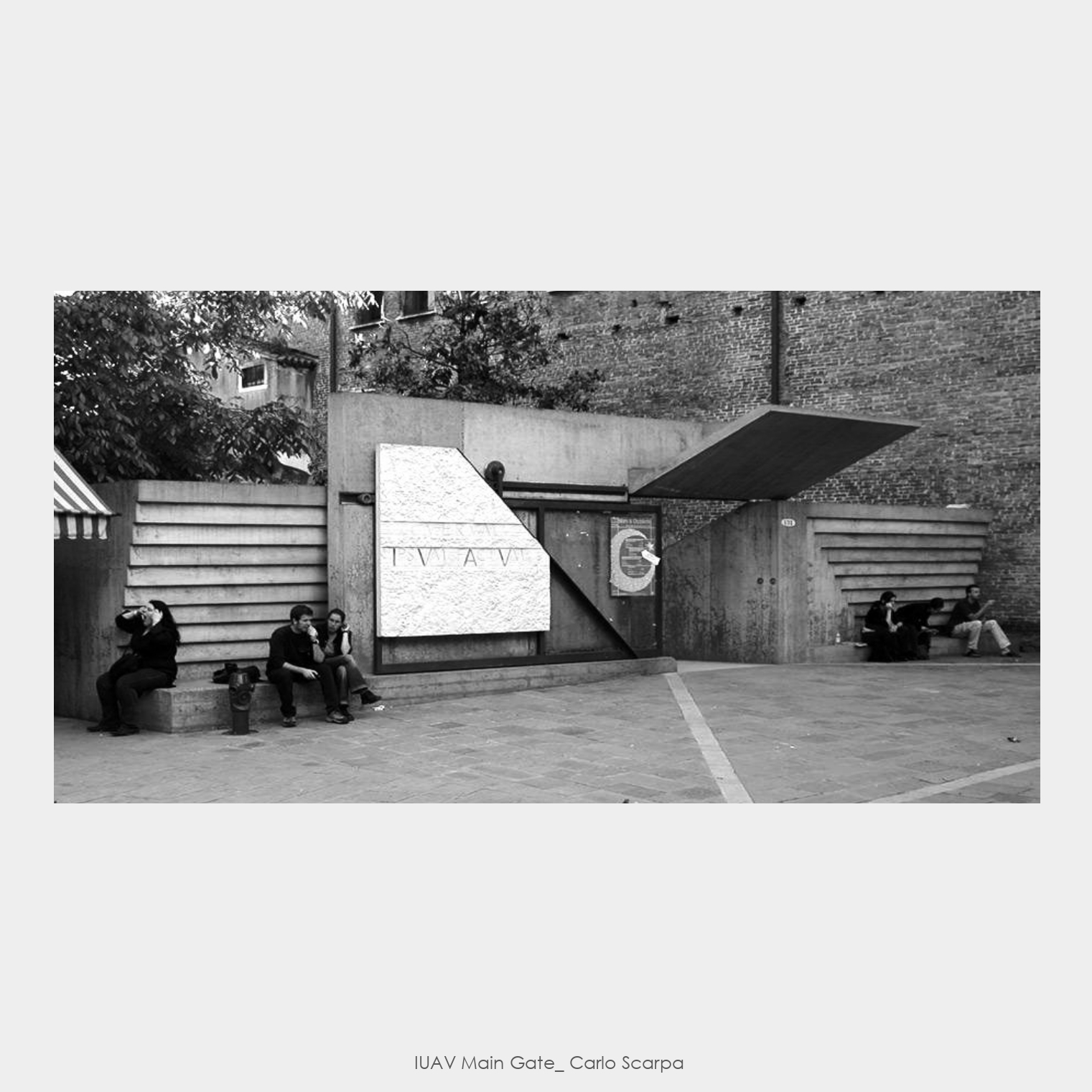

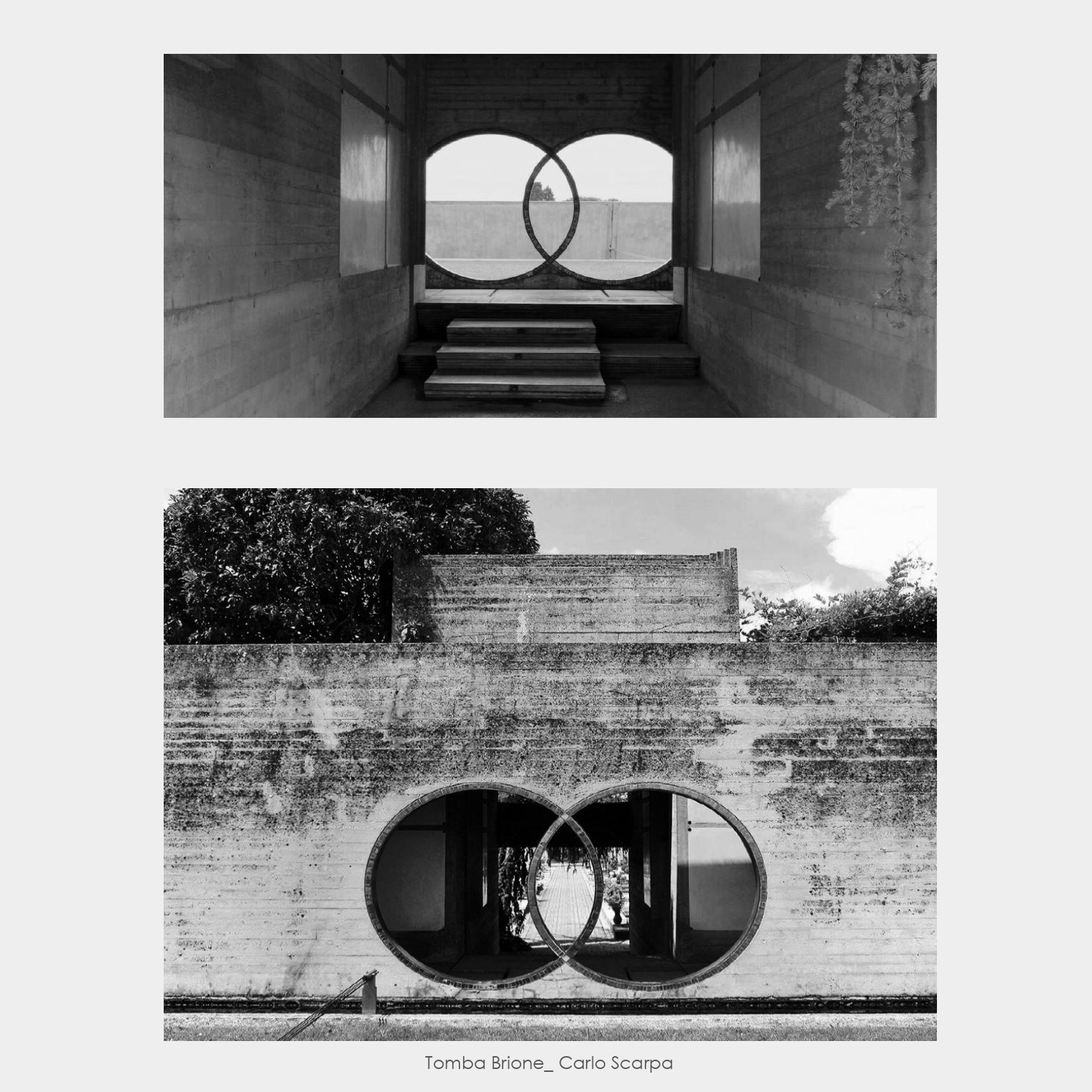

This publication, "Thresholds," explores these questions through the lens of "Books of Copies," a project initiated by

the architectural collective San Rocco. We have created a digital artifact titled "Thresholds," presented in the distinctive layout of these books. Books of copies contain images intend to inspire the

creation of architecture. Books of copies embrace a diversity of architectural expression, excluding only natural forms.

The act of copying here is one of selection and reinterpretation, guided by an appreciation for the inherent

beauty of existing forms.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

P4architecture, is an internationally awarded architecture firm founded in 2014 in Greece, with studios in Athens, Messenia, and Rhodes. They are a research-driven design studio, uniting architects, engineers, and designers who collectively share a set of core values and principles.

Alkiviadis Pyliotis is an Architect-engineer and co-founder of the Architecture studio P4architecture. He studied architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the National Technical University of Athens, where he graduated with honors. He teaches Architectural Design as an adjunct Professor at the Department of Architecture of the University of Patras.

Konstantinos Pyliotis is an architect-engineer and co-founder of the architecture studio P4architecture. He studied architecture at the Architecture School of the National Technical University of Athens. He continued his academic research in the post-graduate master’s program at N.T.U.A School of Architecture, where he graduated with honors.

Evangelos Fokialis is an architect-engineer and co-founder of the architecture studio P4architecture. He studied architecture at Harvard Graduate School of Design and the National Technical University of Athens.

Alkiviadis Pyliotis is an Architect-engineer and co-founder of the Architecture studio P4architecture. He studied architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the National Technical University of Athens, where he graduated with honors. He teaches Architectural Design as an adjunct Professor at the Department of Architecture of the University of Patras.

Konstantinos Pyliotis is an architect-engineer and co-founder of the architecture studio P4architecture. He studied architecture at the Architecture School of the National Technical University of Athens. He continued his academic research in the post-graduate master’s program at N.T.U.A School of Architecture, where he graduated with honors.

Evangelos Fokialis is an architect-engineer and co-founder of the architecture studio P4architecture. He studied architecture at Harvard Graduate School of Design and the National Technical University of Athens.

This is a romantic idea. A romantic approach to transitions, weaving together

notions of memory, inhabitation, and spatiality.

To pair with the images, we share here some notes and ideas within and without transitions.

To pair with the images, we share here some notes and ideas within and without transitions.

In architecture, transitions are not merely utilitarian or programmatic elements; they are profound mediators of spatial and human experience. These spaces are not neutral: they influence social relationships, acting as filters that regulate movement, visibility, and intimacy.

Henri Lefebvre suggests that spaces of transition become arenas where everyday life and social control intersect, charged with cultural and political significance. Robin Evans explores how the architectural arrangement of transitions can either isolate or connect, creating social hierarchies or fostering communal fluidity. Walter Benjamin, in his reflections on arcades, sees transitions—passages—as cultural artifacts, liminal spaces where the flâneur navigates modernity.

Gaston Bachelard, in his phenomenological approach, finds in thresholds poetic and psychological weight, where crossing a door becomes an act of transformation.

Whether it’s the intimacy of a threshold, the anonymity of a corridor, or the spectacle of an arcade, transitions are where architecture becomes experience. Designing these spaces thoughtfully means understanding that every passage is a narrative, every door a decision, and every threshold a moment of becoming.

Today, we believe the modern definition of transitional spaces needs to be extended beyond its inaugural description. We could even dare to imagine that every space is potentially transitional. Simply because of our relationship with cyberspace and digital speed, physical spaces -and objects- have become a transition from which we relate to others. There is no such thing anymore as a space in which we are not intertwined with another one, a space that is not malleable and everchanging (in both form and experience). From encrypted information exchanges to biological cycles, transition is the medium we inhabit.

Even within our practice as designers and twin sisters, every day is a transition. We never see or experience the same thing twice. From the construction to the completion of a project, what we leave after a day’s work is never the same thing that welcomes us the next morning. What we imagine is rarely exactly what takes form in the tangible world. What we draw is a translation of what we envision; what we communicate is a transition from thought to conclusion or from premises to new questions; and what we inhabit is a transition destined for ever-changing outcomes—light, use, furniture, activity, sound, smell, transformation.

In the words of Michel Serres, things have a very soft threshold between the nameable and unnameable, the figurable and the un-figurable, the identifiable and unidentifiable. As images fade in our memory, colliding with other ideas, pictures, spaces, and sensations, they merge into blurry definitions of the transitions we inhabit and those we design. We trace lines on paper and within our built environments, sketching thresholds where architecture meets experience, and experience meets meaning.

We blurred photos of all the homes we have lived in, separately. They haven’t really shaped urban change at a large scale, but they have altered our perception of the urban as global, urban as personal, urban as transitional.

We two have only been roommates once, neighbors once, and have lived across cities and countries for years. However, we have shared spaces of childhood, work, study, and imagination. We made a personal map—a mind map, a memory plan. Without urban grids or avenues, we pinned our residences through blurry images, visualizing transitions not just as movements through space, but as passages through time.

The idea of these images seems to have blurred after an elongated passage of time, turning into a serial diminution from touch to sight to thought. They explore the subject-object relation to things, to the urban, to cities, and to the medium of meaning and imagery related to them. They represent a premonitory idea of how, based on our experience of inhabiting all these spaces, definitions of boundaries and transitions have been conceived at various scales: public and private, intimate or common, inside or outside. In attempting to erase these dichotomic poles, the very definitions of such transitions have permeated our practice; from physical borders to the passage of time.

...

estudio estudio is an architecture, design and research studio, based in Mexico City and founded by Inés Benítez and Nuria Benítez in 2020. Both architecture graduates from UNAM, Inés with a master’s degree from the Harvard Graduate School of Design in Boston and Nuria in the Royal College of Art in London.

Drawing from both research and collaboration as vehicles for design, various forms of creativity allow us to tailor solutions, specific to a physical, cultural, and functional context. They use design as a methodology to solve, represent, rethink, reproduce, reiterate and recreate. The scale of their work is ‘small’, touching upon larger-scale urban and cultural phenomena. They study the intersection between architecture and its narratives within and outside the discipline, bringing together layers that would normally go unnoticed to create projects with multidisciplinary perspectives and participatory processes. They believe that applied creativity is a tool to highlight a specific value and spread the knowledge embedded in each job, in each profession and in each place, as an act of conservation.

Born and raised in Mexico City, they studied Architecture at UNAM

(National Autonomous University of Mexico), graduating with

highest honors.

Inés Benítez

She recently finished her Master in Design Studies in “Art, Design, and The Public Domain” in the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and later completed an “Irving Fellowship” research grant. She has worked as an architect, interior designer, researcher, art producer and exhibition designer. Inés has been Adjunct Professor at Wentworth Institute of Technology and Universidad de los Andes

in Colombia.

Nuria Benítez

She recently studied a Masters in Research at the Royal College

of Art, London, supported by FONCA-CONACYT and Beca Arquitecto Marcelo Zambrano. She has worked at renowned cultural institutions and architecture studios internationally, such as MoMA and Tatiana Bilbao Estudio, as well as started several collaborative practices and experiments. Since 2020, Inés and Nuria founded estudio estudio, a design, architecture and research practice in Mexico City. Since 2021, they are both teaching “Architecture Studio 1” at Universidad Iberoamericana.

Drawing from both research and collaboration as vehicles for design, various forms of creativity allow us to tailor solutions, specific to a physical, cultural, and functional context. They use design as a methodology to solve, represent, rethink, reproduce, reiterate and recreate. The scale of their work is ‘small’, touching upon larger-scale urban and cultural phenomena. They study the intersection between architecture and its narratives within and outside the discipline, bringing together layers that would normally go unnoticed to create projects with multidisciplinary perspectives and participatory processes. They believe that applied creativity is a tool to highlight a specific value and spread the knowledge embedded in each job, in each profession and in each place, as an act of conservation.

Born and raised in Mexico City, they studied Architecture at UNAM

(National Autonomous University of Mexico), graduating with

highest honors.

Inés Benítez

She recently finished her Master in Design Studies in “Art, Design, and The Public Domain” in the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and later completed an “Irving Fellowship” research grant. She has worked as an architect, interior designer, researcher, art producer and exhibition designer. Inés has been Adjunct Professor at Wentworth Institute of Technology and Universidad de los Andes

in Colombia.

Nuria Benítez

She recently studied a Masters in Research at the Royal College

of Art, London, supported by FONCA-CONACYT and Beca Arquitecto Marcelo Zambrano. She has worked at renowned cultural institutions and architecture studios internationally, such as MoMA and Tatiana Bilbao Estudio, as well as started several collaborative practices and experiments. Since 2020, Inés and Nuria founded estudio estudio, a design, architecture and research practice in Mexico City. Since 2021, they are both teaching “Architecture Studio 1” at Universidad Iberoamericana.

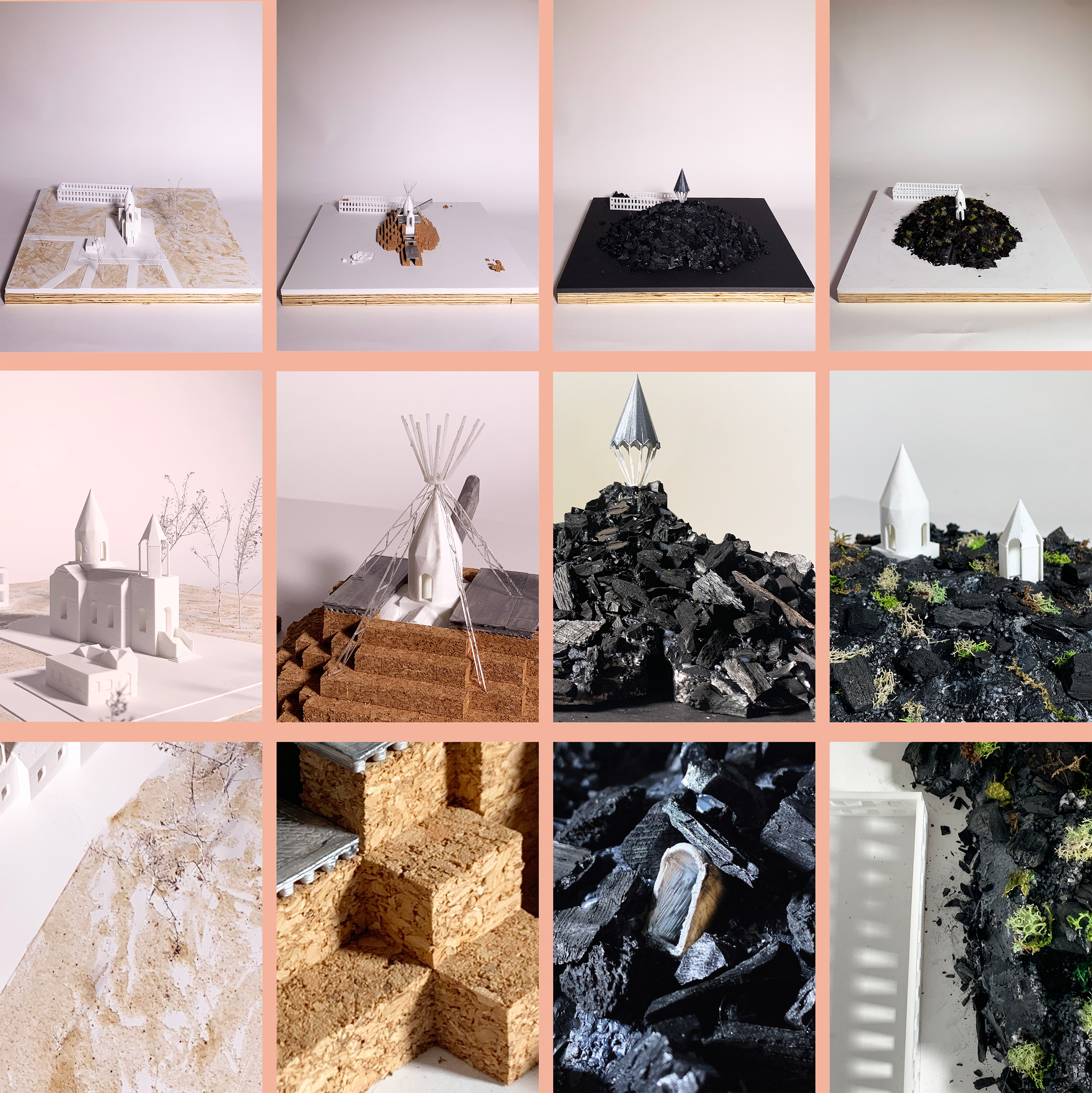

The Politics of Preservation in Nagorno-Karabakh

What happens to heritage in conflict zones?

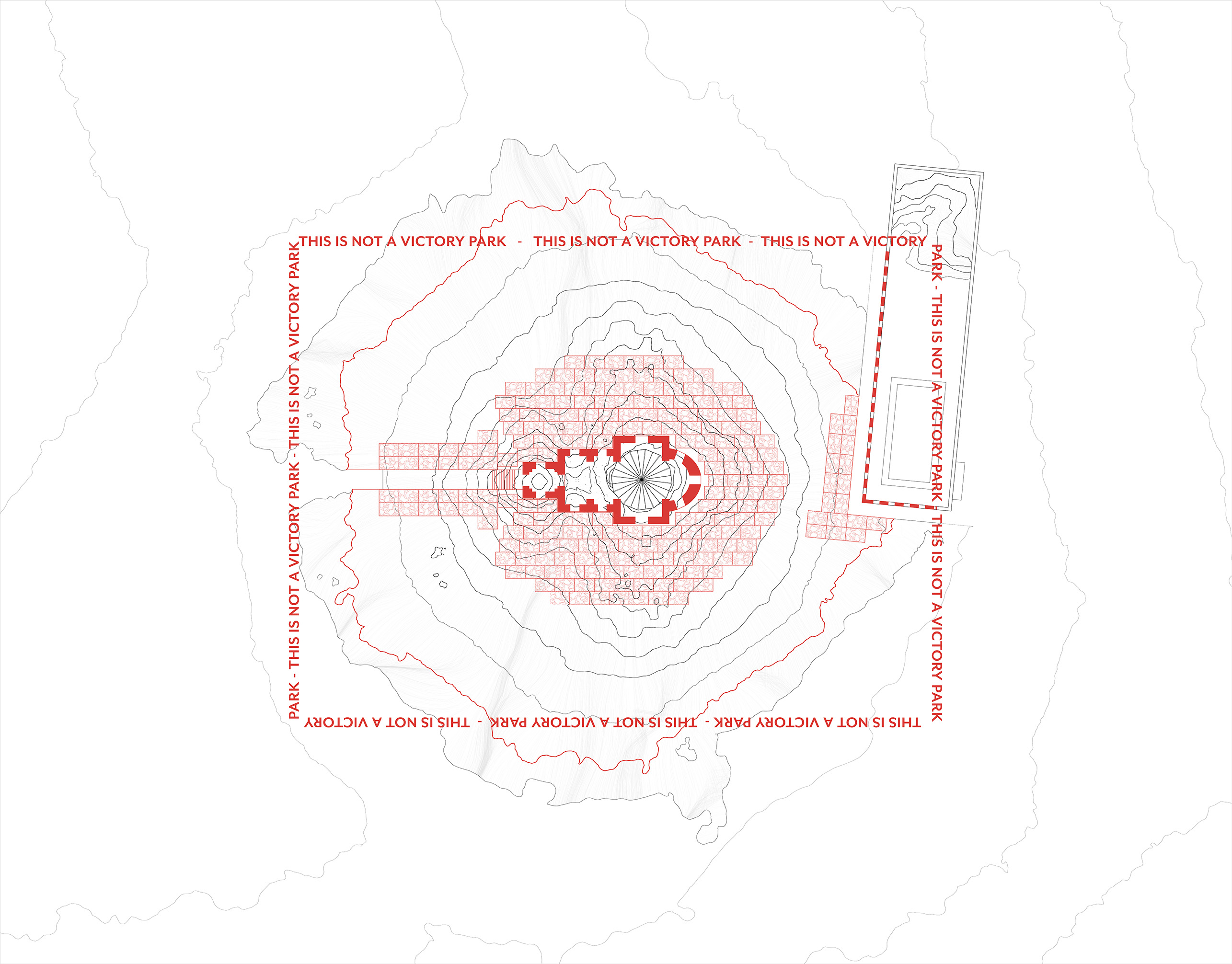

Zham in Shushi. The research responds to the destruction of Armenian heritage by reimagining a "victory park" that paradoxically resists cultural erasure.

The Politics of Erasure

Armenia’s cultural sites, especially churches, have been targets of destruction or revisionist repurposing. The 2020 war saw widespread vandalism of Armenian heritage, with sites like Ghazanchetsots Cathedral modified under the guise of "restoration."

Russian peacekeepers now oversee some of these sites, but their future remains uncertain.

Shushi: A Contested Topography

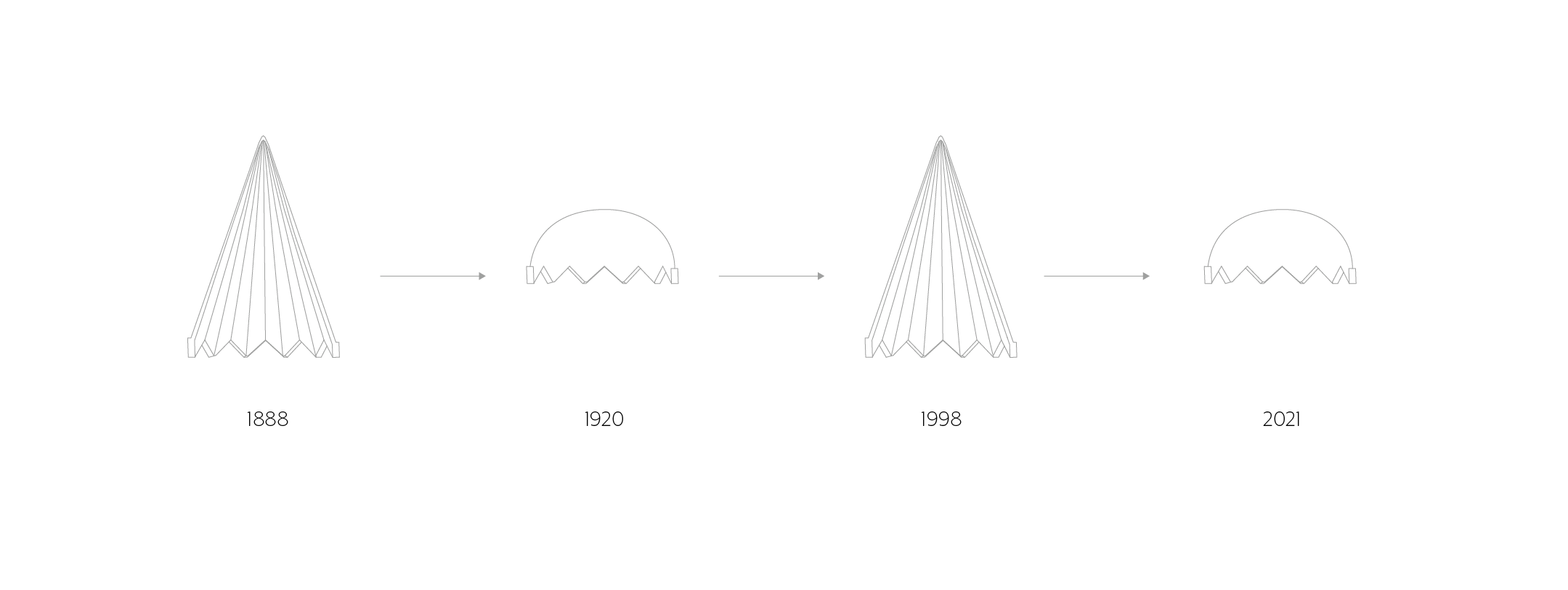

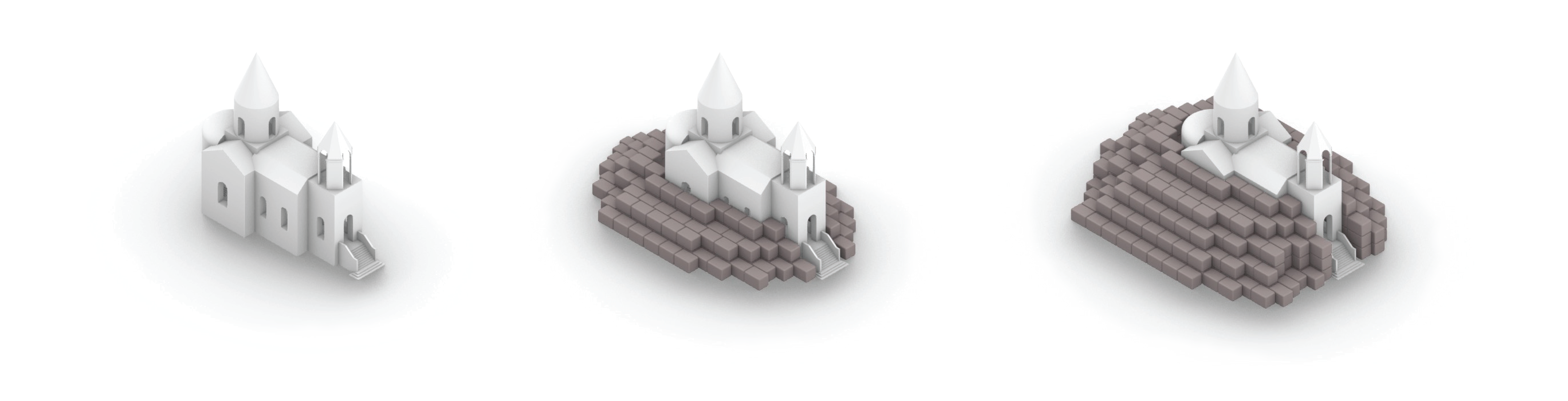

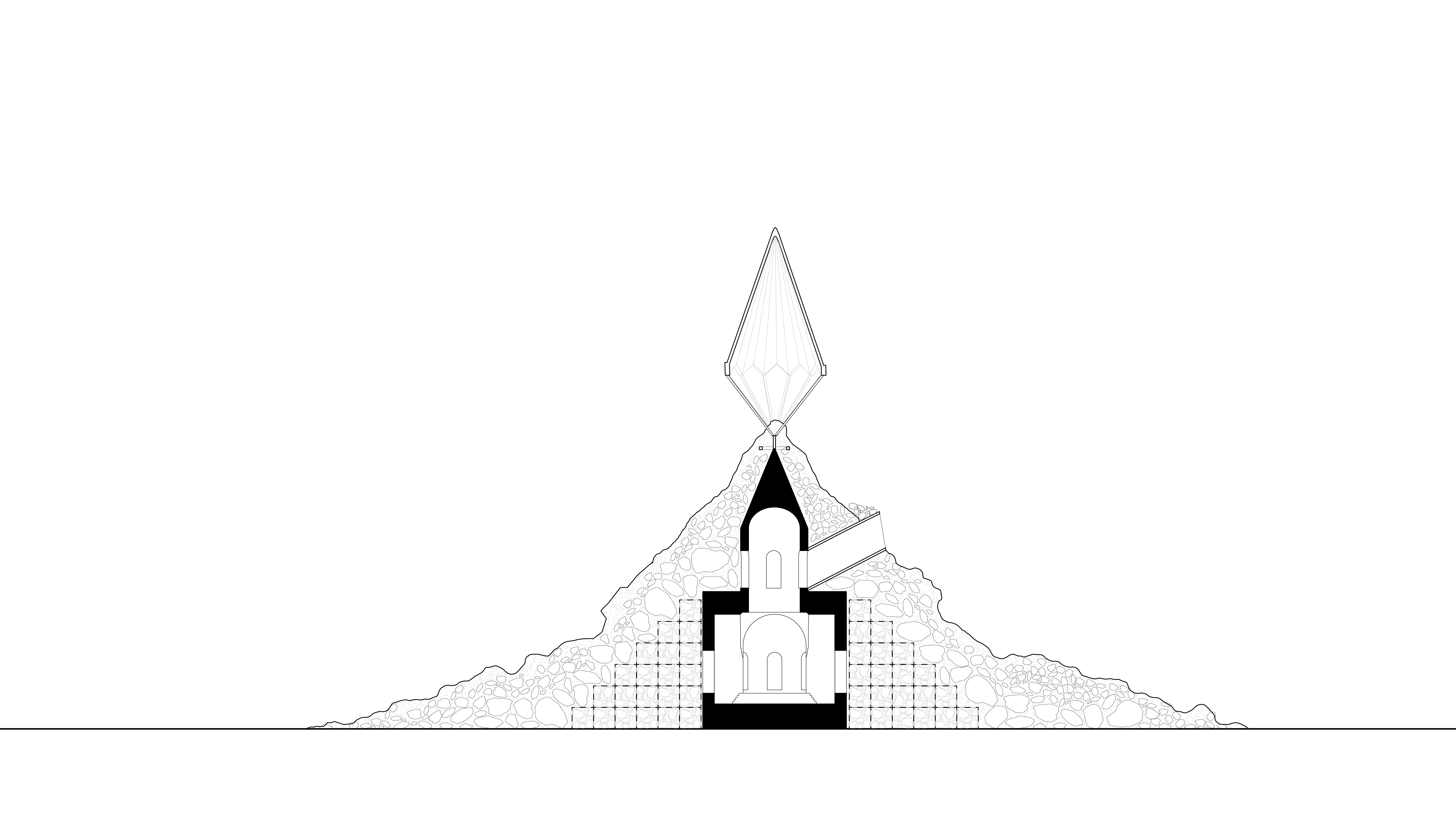

Shushi’s strategic elevation made it a key battleground and now a focal point for cultural rewriting. Kanach Zham, a lesser-known church, was particularly at risk. Inspired by an Azerbaijani writer’s claim that "each Armenian church was the same color as the mountain next to it," this project proposes an artificial mountain that buries and protects the church.

Building with Rubble

Drawing from historical precedents like Berlin’s Teufelsberg, the intervention uses gabions filled with rubble to encase the church in a process of architectural "mummification." A structural framework stabilizes the roof, allowing for potential future restoration while shielding the site from immediate destruction.

A Landscape of Disappearance

The intervention creates a landscape that both hides and preserves, responding to the broader pattern of cultural erasure in the region. Rather than monumentalizing loss, it allows the church to persist in a latent state—neither fully erased nor entirely visible. Two domes within the structure reference Armenian architecture, and the relocated roof of Ghazanchetsots Cathedral reinforces the interplay between hidden and visible heritage.

This project is both an act of preservation and strategic erasure, camouflaging Armenia identity while safeguarding its existence. It challenges the politics of heritage in post-war Nagorno-Karabakh, questioning how we preserve history in a landscape where it is constantly rewritten.

N.B.: This project was developed under the guidance of Sergio Lopez-Pineiro.

The Kanach Zham has been completely demolished, according to satellite research by Cornell’s Caucasus Heritage Watch.

This research was developed before the forced displacement from Artsakh.

Shant Charoian is an architect based in Yerevan, Armenia. A graduate of the Harvard Graduate School of Design with a post-professional Master of Architecture, he also holds a BA in Architecture from California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, where he earned the Outstanding Senior Project prize. In 2023, he established Jardar NGO to advance architectural thinking in Armenia, currently hosting The Oshakan Project, a summer school that reimagines heritage and sustainable construction in Armenia, and Line: Armenian Architecture Biennial, an event that will address community challenges and advocates for transformation through thoughtful work with Armenia’s public spaces.

"This space with no doors" is a soft installation designed for the "Cover Me Softly" theme of the architecture biennale in Timișoara, Romania. This innovative project serves as a nexus, interweaving diverse threads of scholarship, artistic practice, and activism to explore the intricate relationships between embodiment, nature, and female activism. Drawing inspiration from the groundbreaking work of Labelle Prussin, Yona Friedman, and Moussa Ag Assarid, the installation challenges conventional architectural paradigms and invites viewers to reconsider the politics of space across multiple scales.

At its core, this project is an extension of the Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory's ongoing engagement with spatial politics, ranging from the intimate scale of the human body to the broader ecological systems that shape our world. By focusing on the often-overlooked realm of domestic arts, particularly embroidery and textile production, the installation illuminates how creative practices can simultaneously reinforce and challenge societal norms while fostering connections between individuals, communities, and the natural environment. The tecniques explored in this installation, rooted in extensive research conducted in the Sahel region and recent collaborations with Romanian artisans, serve as a poignant reminder of the rapid disappearance of traditional knowledge due to colonization, climate migration, war, and the relentless march of industrialization, globalization, and automation. By engaging with local women passionate about preserving traditional embroidery and domestic craft skills, the project not only highlights the importance of cultural heritage but also empowers communities to resist the erasure of their valuable practices.

This installation draws parallels between the nomadic architecture of the Tuareg, as explored by Prussin, and the experimental, non-extractive approach advocated by Friedman. It celebrates the role of women as primary architects of nomadic environments and challenges the male-dominated narratives that have long dominated Western architectural discourse. Through its focus on local materials, regenerative practices, and participatory design, "This space with no doors" offers a vision of architecture as a collective, feminine endeavor that nurtures sustainable relationships between people and their environment.

By weaving together these diverse elements - from the practical wisdom of nomadic tent design to the empowering potential of Friedman's architectural manuals - the installation creates a multifaceted narrative that resonates with Romania's rich textile heritage while addressing global concerns about cultural preservation, environmental sustainability, and social justice. As visitors engage with the woven fabrics, embroidered patterns, and handmade elements, they are invited to reflect on the power of domestic arts to tell stories, preserve identities, and imagine more equitable and sustainable futures.

The experimental practice of Yona Friedman and the scholarship of Lebelle Prussin, in the lookout for architecture in the scale and nature of the body, the now, the non-extractive, and the non-speculative. Like the Tuareg millennia-old tent – a space shaped by the journey of a girl growing into a woman, continually accumulating skills and craft throughout her life which are reflected in the type of tools and layers of ornaments within the tent. Layers that reveal patches of history, love, the transformation of life and encounters over time. Or the “Roofs” handbook by Yona Friedman, which he deemed the most important architectural element, its elements are capable of literally growing, being harvested, and assembled anywhere. In response to the extractive nature of architecture, real estate, and neoliberalism, Friedman developed handbooks and manuals to share technical skills with the public, empowering them to build their own homes. The stories of Ag Assarid, a poet, artist, and spokesperson for the Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, reveal a deeper connection between humans and nature – we are one, not separated, yet covered by a thin veil, a cloth, a patch of leather, or a woven wool that adjusts its thickness with the changing season and suspended from a branch of a tree.

Nomadic Architecture

I came across the work of Lebelle Prussin before my trip to Mali in early 2016. Mali’s disputed northern territory is home to ancient cities which still reflect the beauty of nomadic culture. Before my visit, I had a lengthy discussion with Moussa Ag Assarid, a Tuareq and the spokesperson for the Movement for the Liberation of Azawad.

Moussa was born in a tent in the area between Gao and Timbuktu, two ancient cities along the Niger River that have thrived for millennia, thanks to the harmonious coexistence of sedentary and nomadic lifestyles. These cities, on the edge of the Sahara Desert, see seasonal fluctuations in population, accommodating pastoralists, desert nomads, fishers, and farmers. Despite their age-old existence, Moussa’s community, also known as the nomads of the Sahara, continues to struggle for international recognition and self-determination. The violence they face has persisted since the early days of the colonization of Africa.

According to the book Land, Man and Sand, in the early 1900s, French colonization profoundly altered Tuareg society and their spatial organization by isolating pastoralists and confining them to a nomadic zone, depriving them of essential southern markets and cereals. This territorial partitioning clashed with the Tuaregs’ traditional land use, reducing the power of existing chiefs and creating new ones, which led to the great revolt of 1917. The revolt, which was eventually suppressed, resulted in significant loss of life and livestock, leading to widespread impoverishment among the Tuareg. The centralization of political power in bureaucratic organizations, unresponsive to local and ecological conditions, further entrenched the disadvantages faced by the nomadic Tuareg people.

This wasn’t the only rebellion. From my conversation with Moussa and limited archival research, I learned that since the beginning of the 20th century, the Tuareg people have rebelled four times. The first major rebellion, as mentioned above, occurred in 1916 against French colonial rule, spurred by a prolonged drought that threatened the Tuareg existence and livelihood. The second rebellion, from 1962 to 1964, followed Mali’s independence and was driven by dissatisfaction with the partitioning of the Sahara by colonial powers, which left the Tuareg dispersed across four nations. Another revolt unfolded from 1990 to 1995, sparked by demands for autonomy amidst drought, famine, and the 1980s economic crisis. This uprising culminated in a peace agreement with the Mali and Niger governments, leaving the Tuareg aside. During this rebellion, the Libyan government attempted to stabilize the region and supported the Tuareg with employment and economic aid. However, after Gaddafi’s fall in 2012, the Tuareg found themselves alone again and fled Libya south to the Sahara, establishing the MNLA. As they moved into Mali with other militarized organizations to capture land, they were halted by the French army and a UN resolution, marking the beginning of a new peace mission.

The quasi stability, however, didn’t last long, and Mali is now facing another militarized coup. The new government asked the UN to leave the country while being helped by mercenaries led by the group formerly known as Wagner to violently displace tens of thousands of people, including nomadic and semi-nomadic communities away from Mali and south to Mauritania.

When talking with Moussa, he spoke passionately about desert cities and how their knowledge and perspective are under a continuous process of erasure. According to him, desert cities are horizontal, submerged with the landscape. “I was born and raised in a tent made of old clothes. A tent is part of nature, and the outdoors is my home. The desert is a flat construct, and our cities have no limits. They embrace this vastness and flatness. We believe that capitalist cities and European cities are mostly vertical, dense with tall buildings. For us, their physical structure manifests inequality. Our desert cities will embody justice and equality in their horizontal shape. They will be able to shrink and expand flexibly to allow access for all.”

These ideas challenge our western understandings of space, time, materiality, and justice, as well as the lifestyles and values that shape our vision of the future.

Space, Place and Gender

In the book African Nomadic Architecture, Space, Place and Gender, Labelle Prussin refers to the tent as architecture, despite its temporary nature. According to her, to understand the architecture of the tent, we must examine the correlation between the nature of desert life and the technology of transportation. The shape, size, and construction method of a tent are contingent on means of mobility.

She distinguishes the indigenous African tent from the missionary tent; while the first is considered home and a complex space of social reproduction and family life, the second, in her view, can be referenced as a political or religious institutional symbol that can be traced back to the Roman military, the Crusaders, the explorers of the Age of Reason, and the missionaries of modernity.

Prussin’s research is situated at the intersection of history, ethnography, and gender studies. She offers another differentiation between indigenous and institutional tents: the former are designed and built by women; the latter by men. Whereas women were the architects of the nomadic built environment, men were the designers of military bases. These discrepancies can be read in the form, tactility, and production processes of each.

Prussin draws another connection between modernist architecture and the institutional tent in an allusion to “a primitive temple” referenced by Le Corbusier. His book Towards a New Architecture celebrates the achievement of the engineer: “The Engineer’s Aesthetic and Architecture – two things that march together and follow one from the other – the one at its full height, the other in an unhappy state of retrogression” As he continues to develop the logic of measures, he dedicates a section to regulating lines as an invisible architectural element. The tent is used in his narrative as an object that connects the past and the future of architecture as an engineering project. In his theories of measure and modular design, the primitive temple – created by “he who builds a shelter for his god” – constitutes the model of perfect proportions.

This extractive and modular pursuit of Le Corbusier, who elevated the engineer to a god-like scale, was contrasted by Prussin, who dedicated decades of her life to documenting the beautiful architecture of nomadic cultures in Africa, specifically in the Sahel.

Prussin’s meticulous research linked the design of the nomadic tent to women, who were the primary architects of the nomadic built environment. They selected the site, planned the camp, and built and adorned its tents.

In her book “African Nomadic Architecture, Space, Place, and Gender,” Labelle Prussin argues that despite its transient nature, the tent should be recognized as architecture. She emphasizes understanding the architecture of the tent involves examining the relationship between desert life and transportation technologies. The shape, size, and construction of these tents are directly influenced by mobility needs, particularly through the labor practices of women who play a pivotal role in shaping nomadic environments. This influence is evident in the design, texture, and production methods of tents, camps, and the cultural and social practices of Tuareg and other African nomadic communities.

According to Prussin, “Nomadic cultures are, however, elusive, difficult to document and record. Nation states have always had problems with their nomadic population and have sought to settle them. Nomads do not observe political borders; they do not pay taxes; they are fiercely independent and live outside the cultural pale.”

Among the Tuareg, both northern and southern, the significance of the tent is deeply embedded in cultural practices, especially around marriage ceremonies. The term for marriage (eduben or ehen) is synonymous with the term for tent (ehen). There are various expressions related to marriage tied to the tent, such as “to set up a tent” or “to fabricate or make a tent” meaning to get married. Additionally, inquiring about marital status involves asking “Have you made a tent?” For men, marrying means “to enter a woman’s tent.” The womb is metaphorically referred to as a tent, and women collectively can be referred to as “those-of-the-tents.”

The circular shape and rounded roof of the tent symbolize the vault of heaven. Typically, tents are made from mats woven from young dum palm tree leaves, cloth, or vellum, attached to a sturdy wooden frame with cords. The dimensions, shape, and texture of these mats often signify wealth and social status within the community. Notably, the tents are exclusively designed and constructed by women, who serve as the sole architects and owners of these integral structures.

Prussin’s work redefines how we map and understand tent types in relation to ethnic origins and geographic movements. She meticulously details the configuration of tents, their construction processes, interior layouts, and their social and political significance within African nomadic cultures, critically aligning these insights with Western disciplinary canons.

Handbooks

In 2015, I visited then-93-year-old Yona Friedman in Paris. Friedman studied architecture in Hungary and Israel. Having witnessed the devastation of the world wars, he dedicated much of his life to improving lives by sharing what he called his “technical skills” through computer programming, animation, teaching, writing, and large-scale and participatory installations. His oeuvre, which was produced outside the conventional realm of architecture, found points of intersection with various United Nations agencies and the art world.

Friedman’s response to our globalizing world was the creation of manuals and protocols that provided essential training and shared construction and design technics through simple instructions and illustrations. These manuals were concerned with the lack of access to resources, growing disparities between rich and poor, and the environmental devastation caused by industrialization, war, and a globally expanding arsenal of nuclear weapons.[i]

Take, for example, Roofs. Produced in 1991 in collaboration with the UN Communication Centre of Scientific Knowledge for Self-Reliance, the manual primarily addressed the lack of shelter among people with the lowest levels of income in India.[ii] Friedman argued that everyone should be able to afford a house through cash purchase or self-construction. A proponent of nonextractive architecture, he believed that houses need to be built of local, regenerative materials that carry minimal environmental effects.

In his manuals, Friedman emphasized the importance of self-reliance and argued that housing projects must allow continuous access to basic needs including water, clean air, renewable energy, and regenerative food production through unsophisticated means like cisterns and windows. His approach rejects the use of supply chains that move materials worldwide and that push up housing costs, contribute significant carbon emissions, and cause environmental degradation. Friedman’s manuals are still relevant, especially now, at a time when the increased use of housing as a financial investment has created an unprecedented housing crisis. In 2021, in the US alone, more than half a million people[iii] were unhoused and deprived of a basic human right.[iv]

While Roofs specifically addressed the housing crisis among India’s lowest caste, Friedman’s solutions have environmental, social, and cultural benefits for all strata. His manuals challenge the architecture field’s complicity in pricing millions of residents out of their cities, communities, and homes. Roofs is an act of radical care by design. It includes care for oneself, care for others, and care for the environment, and it provides a space of hope in precarious times. During our conversation in Paris, Friedman explained that the art world and its galleries, exhibitions, festivals, and socially engaged outdoor installations allowed him the freedom to try new ideas and to develop prototypes that were not supported by the architecture profession and its marketplace.

Embroidery and Textile

The inspiring work of Lebelle Pussin , Yona Friedman, and Moussa Ag Astrid help envision an alternative to the male-dominated and exploitative nature of modern Western architecture cannon and practice. Their ideas empower us to consider a more local, participatory, and organic approach to making architecture a collective feminine endeavor. This space has no doors installation for the “Cover Me Softly” biennale, covers Friedman’s open-ended design guidelines that can be adapted and utilized by anyone wishing to build and cultivate their homes in any setting, and Pussing’s emphasis on the domesticity and powerful social spaces not defined by patriarchal norms but by nature and nurture—a roof, a tent, a home, gradually nurtured by women throughout their lives.

Drawing on the artistic practices that originate from domestic spaces offers profound insights into the intricate relationships between gender, local cultural production, and nature. By examining the elements, technical skills, and crafts that emerge from these intimate environments, we can uncover how these creative expressions both shape and reflect societal norms and values. Consider, for instance, the art of embroidery and textile production. These time-honored crafts serve as compelling examples of how domestic artistry intertwines with broader cultural narratives. Deeply rooted in both social traditions and material culture, they transcend their functional origins to become powerful forms of cultural production and expression.

The use of natural dyes exemplifies this connection between art and environment. In Romanian craft, oak bark dye has been traditionally used to color fabrics and threads, imparting earthy tones that reflect the region's cultural heritage. Similarly, nomadic cultures of the Sahara, as studied by Lebelle Prussin, utilize red-brown tannin extracted from Acacia trees for textile purposes. These practices showcase how women, through their mastery of dyeing techniques, not only preserve artistic traditions but also nurture a sustainable relationship with the land, enriching their communities' cultural and aesthetic identities.

The choice of materials further illustrates this deep connection between craft and environment. The Tuareg people of the Sahara region, for example, are renowned for their rich embroidery on leather goods and garments. Using readily available materials like goat or camel leather, cotton threads, and embellishments such as cowrie shells and silver, Tuareg women create complex geometric patterns that tell stories and express their cultural history. In Romania, hemp has played a central role in craft and culture for centuries. Its versatility and sustainability have made it an ideal base material for traditional embroidery and textiles. The ongoing cultivation of hemp, adapted to Romania's varied climate, aligns with ecological agricultural practices and underscores the enduring link between craft and local resources.

Embroidery and textile production skills not only adorn and enhance everyday objects but also weave together stories of identity, heritage, and lived experiences. They serve as tangible links between the personal and the collective, often preserving and transmitting cultural knowledge across generations. Moreover, these practices historically align with gendered divisions of labor, offering a unique lens through which to examine the roles and expectations placed on women in various societies. At the same time, they highlight the often undervalued artistic contributions that emerge from traditionally feminine spaces. Women play a crucial role in these artistic expressions, passing down their knowledge and skills to future generations, thus ensuring cultural continuity.

These examples from Romanian and Saharan cultures illustrate how traditional embroidery and textile practices, shaped by local materials and environmental conditions, create rich narratives of identity and heritage. Women play a pivotal role in cultural reproduction and the preservation of artistic traditions, ensuring the continuity of these valuable practices across generations. By exploring domestic arts, we gain a richer understanding of how creative practices can simultaneously reinforce and challenge societal norms, while also fostering connections between individuals, communities, and the natural world that inspires much of this artistry. As these concepts interweave into a new narrative within an old industrial space in Romania through the installation "this space has no doors," they seek to resonate with the long-standing local culture of crafts, skills, technology, creativity, and feminine heritage. By engaging with women, the installation—featuring woven fabrics, embroidered drawings, patterns, and handmade pompoms—aims to highlight the importance of cultural heritage and forms of knowledge that are quickly disappearing, first overtaken by the Industrial Revolution and now by automation. Here, at the modernist industrial complex, we hope to draw attention to these valuable traditions and practices.

Soft Cover in Tsimerova

The textile cover at this biennale space weaves stories and ideas across cultures and places, experimenting with the agency of design and architecture to tell stories, collaborate, and activate local spaces and crafts. This soft roof (under the industrial building’s roof) invites interpretation and engagement from all those who participated in its production. By engaging with the local, the making process seeks to breathe life into, or mention a few, suppressed stories and histories affected by colonization, extraction, and marginalization that are both site-specific and global.

Building on Romania’s rich history of textile making, this project invites local weavers and embroiderers to participate in the installation of a tent and its various elements: poles, textiles, embroidery, locally produced organic dyes, and a set of drawings and construction techniques drawn from nomadic cultures, as researched by Lebelle Prusin. These elements serve both decorative purposes and as manuals for construction and textile art.

By utilizing local crafts and knowledge, the tent aims to foster conversations with local women committed to preserving traditional crafts from becoming obsolete. The biennale team facilitated this process by helping to identify and collect locally produced textiles made from hemp, a material traditional to Romanian culture, while selecting a local dye derived from tree stems, similar to those used by nomadic communities in Africa.

The space beneath the tent is designed for assembly and collaboration, featuring seating and a larger round table for workshops. Textiles and pom-poms crafted by local women adorn the tent and are available for sale at the biennale, with all proceeds going directly to the embroiderers and an emerging embroidery club.

Thus, the exhibition serves as a platform for preserving cultural heritage and promoting local textiles and crafts. The project emphasizes women’s agency in creating safe spaces filled with love, beauty, and care. This multilayered tapestry employs ephemeral interventions and fabric as mediums to convey narratives and ideas, ranging from aesthetic motifs to preservation.

References:

Prussin, Labelle. African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place, and Gender. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995.

Shoshan, Malkit. BLUE: Architecture of UN Peacekeeping Missions. Actar, 2023.

Friedman, Yona. Energy and Self-Reliance Handbook. 1986.

Friedman, Yona. "Roofs." Internet Archive, 1986, archive.org/details/Roofs-PartOne-English-YonaFriedman.

Malkit Shoshan is a designer, researcher, and writer, and founding director of the architectural think-tank FAST (Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory) that operates at the intersection of architecture, urban planning, and human rights. FAST’s interdisciplinary work investigates the impact of systemic violence on people’s lived environments and aims to promote social and environmental justice through collaborative initiatives and designs. She is also the 2024 Senior Loeb Scholar and Design Critic at Harvard GSD.

In 2021, Shoshan was awarded the Silver Lion at the Venice Architecture Biennale for her collaborative project Border Ecologies and the Gaza Strip: Watermelon, Sardines, Crabs, Sand, and Sediment, which is also the subject of her forthcoming book with Amir Qudaih (Mack Books). In 2016, she curated the Dutch Pavilion at The Venice Architecture Biennale. Shoshan is the author of the award-winning book “Atlas of Conflict: Israel-Palestine” (Uitgeverij 010, 2010), “Village: One Land, Two Systems and Platform Paradise” (Damiani Editore, 2014), and “BLUE: The Architecture of UN Peacekeeping Missions” (Actar, 2023). Her additional publications include “Zoo, or the letter Z, just after Zionism” (NAiM, 2012), “Drone. UNMANNED. Architecture and Security Series” (DPR-Barcelona, 2016), “Retreat. UNMANNED. Architecture and Security Series” (DPR-Barcelona, 2020), “Spaces of Conflict,” TU Delft Architecture Theory Journal (JAP SAM Books, 2017), and “Greening Peacekeeping: The Environmental Impact of UN Peace Operations”.

Her research and design work have been featured in leading newspapers and magazines, including the New York Times, The Guardian, NRC, Haaretz, Volume, Surface, Frame, Metropolis, and Harvard Design Magazine, and her work has been exhibited internationally at the Venice Architecture Biennale (2002, 2008, 2016, 2021), Cooper Hewitt (2021-2023), Rotterdam Architecture Biennale (2011, 2022), UN Headquarters in New York City (2016), Harvard GSD (2017, 2020), NAiM/Bureau Europa (2012, 2021), Boijmans Museum (2016), Het Nieuwe Instituut (2014), Istanbul Design Biennale (2014), Israel Digital Art Center (2012), and Netherlands Architecture Institute (2007).

In 2021, Shoshan was awarded the Silver Lion at the Venice Architecture Biennale for her collaborative project Border Ecologies and the Gaza Strip: Watermelon, Sardines, Crabs, Sand, and Sediment, which is also the subject of her forthcoming book with Amir Qudaih (Mack Books). In 2016, she curated the Dutch Pavilion at The Venice Architecture Biennale. Shoshan is the author of the award-winning book “Atlas of Conflict: Israel-Palestine” (Uitgeverij 010, 2010), “Village: One Land, Two Systems and Platform Paradise” (Damiani Editore, 2014), and “BLUE: The Architecture of UN Peacekeeping Missions” (Actar, 2023). Her additional publications include “Zoo, or the letter Z, just after Zionism” (NAiM, 2012), “Drone. UNMANNED. Architecture and Security Series” (DPR-Barcelona, 2016), “Retreat. UNMANNED. Architecture and Security Series” (DPR-Barcelona, 2020), “Spaces of Conflict,” TU Delft Architecture Theory Journal (JAP SAM Books, 2017), and “Greening Peacekeeping: The Environmental Impact of UN Peace Operations”.

Her research and design work have been featured in leading newspapers and magazines, including the New York Times, The Guardian, NRC, Haaretz, Volume, Surface, Frame, Metropolis, and Harvard Design Magazine, and her work has been exhibited internationally at the Venice Architecture Biennale (2002, 2008, 2016, 2021), Cooper Hewitt (2021-2023), Rotterdam Architecture Biennale (2011, 2022), UN Headquarters in New York City (2016), Harvard GSD (2017, 2020), NAiM/Bureau Europa (2012, 2021), Boijmans Museum (2016), Het Nieuwe Instituut (2014), Istanbul Design Biennale (2014), Israel Digital Art Center (2012), and Netherlands Architecture Institute (2007).